When touring, they tested a respected hall’s ban on Black performers, intended to discourage Black audiences. Controversy ensued when Scott’s concert was canceled upon realizing she was Black.

STARRING HAZEL SCOTT: TAKING A SWING AT SEGREGATION

TOURING

Scott met segregation by asserting demands for accountability.

[2]

While initial efforts to end the DAR’s ban and tax exemption failed, Scott spurred significant protest within DAR and from civil rights groups.

[4]

. . . Miss Scott . . . wired that ‘two precedents’ hindered her from appearing:

‘1. The fact that the National Press Club excludes Negro Journalists even though they are members of the American Newspaper Guild, whose membership consists of both white and Negro correspondents.

‘2. As you know, the Negro journalists have been excluded from the press galleries of the House and Senate.

‘I trust that the day will come soon when qualified journalists of my race will be accepted without distinction.’” [5]

‘What justification can any one [sic] have who comes to hear me and then objects to sitting next to another Negro,’ the pianist told a reporter for the Austin American.

Miss Scott was billed to appear at . . . the University of Texas. The show . . . was a sellout with 7,000 seats sold. Money was being refunded.” [6]

[7]

What amazed me was the ferocity of some of the resistance. . . . They would call the police, in Texas, they called the Texas Rangers, that . . . ‘how dare she challenge this.’” [8]

As one of the first to boycott segregated audiences, Scott’s actions amplified nationwide and grassroots anti-segregation efforts that loosened segregation policies at each institution Scott protested within a decade.

The Trial

Scott cited Washington’s Civil Rights Statute, only the fifth person to do so, for treatment unassociated with the north.

. . . a surprise rebuttal witness . . . thought that Scott ‘conducted herself in a lady-like manner and did not shout or tap people on the shoulder, use profanity, or threaten to tear apart the waitress.’ [10]

Scott won the suit and $250 that she donated to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, giving legal precedent and momentum to local organizations that resulted in new laws against discrimination.

[1] Karen Chilton, Hazel Scott: The Pioneering Journey of a Jazz Pianist, from Café Society to Hollywood to HUAC, 2016

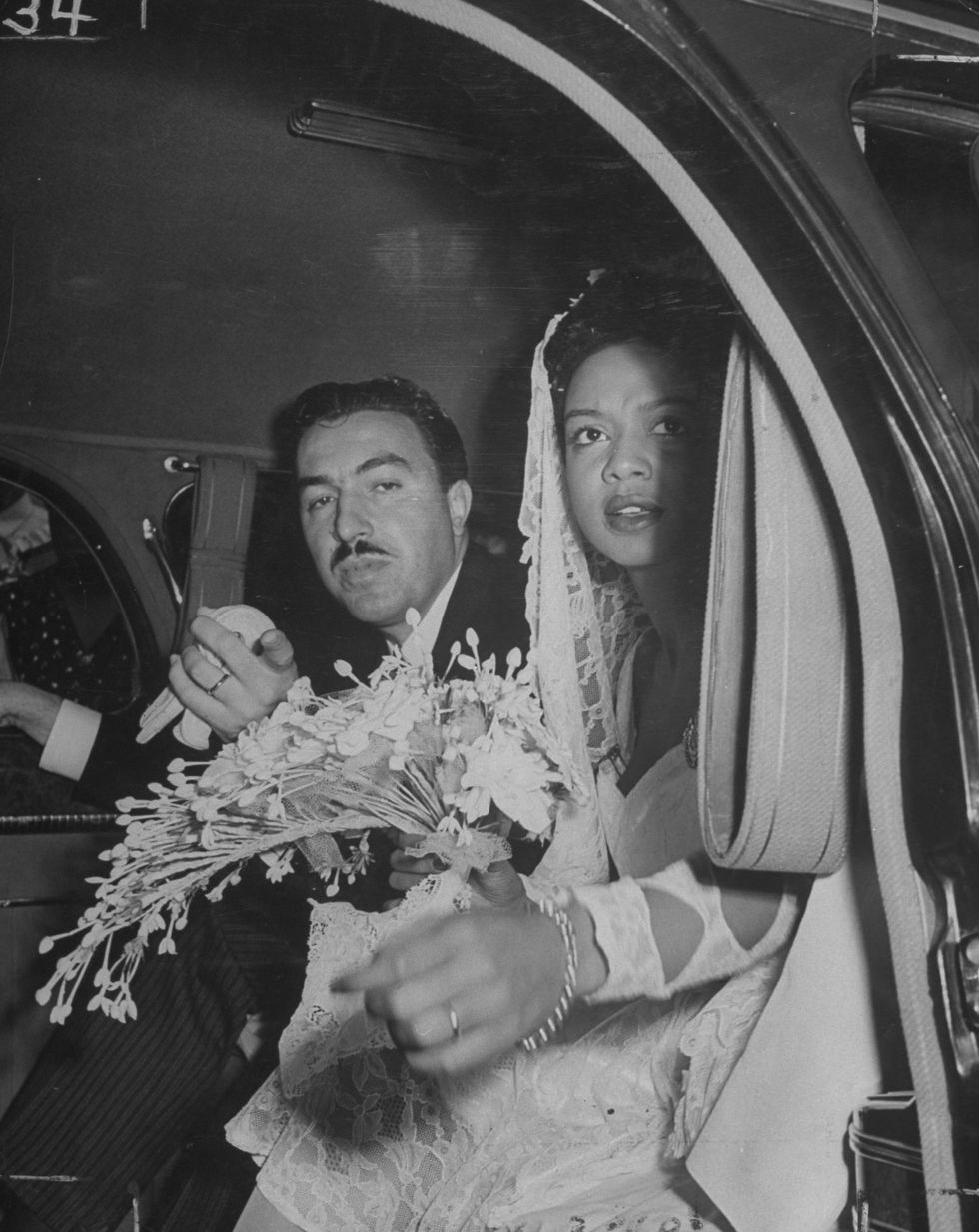

[2] Wedding of Hazel Scott and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.'s, 1945, Harper's Bazaar

[3] The New York Times, "Truman Condemns Negro Ban," October 13, 1945

[4] "Protest DAR bar of Hazel Scott," October 16, 1945, Flickr

[5] Evening Star, "Hazel Scott Cancels Press Club Concert," November 11, 1945

[6] Evening Star, “Hazel Scott Refuses to Play At Segregated Hall in Texas,” November 16, 1948

[7] "Hazel Scott at Lewisohn Stadium, NYC," 1947, Ruth Orkin Photo Archive

[8] Adam Clayton Powell III, Zoom interview by the author, May 12, 2021

[9] Powell v. Utz. Federal Supplement, 1945

[10] Dwayne Mack, "Hazel Scott: A Career Curtailed," 2006

Anita Dinakar

Starring Hazel Scott: Taking a Swing at Segregation

Senior Individual Website

Website Word Count: 1200

Multimedia Length: 2 minutes and 59 seconds

Process Paper Word Count: 500