Upon first glance, The Birth of a Nation seems innocuous enough. The bulk of the scenes are action-packed, popcorn-munching distractions for the masses quick to hand over a week’s wages for an afternoon of entertainment. Given the era in which it was released, however, it’s no wonder the Black community was riled up by the film.

Lights, Camera, Action, Cut:

The Delayed Critique of D.W.Griffith's

The Birth of a Nation

Legacy

“Given these circumstances, it’s hard to understand why Griffith’s film merits anything but a place in the dustbin of history, as an abomination worthy solely of autopsy in the study of social and aesthetic pathology” (Brody, 2013).

The Birth of a Nation debuted some 40 years after the Civil War, a period short enough for people like Griffith to have relatives who saw the battlefield first-hand. It was also the height of the Great Migration, when Blacks moved to industrialized cities in droves. As this was 50 years before the Civil Rights movement, Blacks continued to face segregation, leading to the founding of the NAACP and other urban leagues. The film, therefore, intersected the interests of whites whose bedtime stories hadn’t yet been corrected by history books, and Blacks who were making every effort to step away from a culture of mistreatment.

Founding of the Urban League (Library of Congress, 1910)

The film thus led to growth in both organizations:

“Towards the end of 1915, after acknowledging Griffith's success in having his film shown virtually everywhere with few, if any, restrictions, Secretary Nerney noted that the ‘NAACP office is flooded with applications for help from all over the United States and even from Canada.’ In effect, the campaign against Birth had elevated the association to a position of national stature and indeed preeminence in the struggle for civil rights in America” (Weinberger, 2011).

“There is no doubt that Birth of a Nation played no small part in winning wide public acceptance for an organization that was originally founded as an anti-Black and anti-federal terrorist group” (History.com Editors, 2022).

It took over a decade for the film to morph from Hollywood blockbuster to KKK propaganda. Ultimately, The Birth of a Nation was banned in just two states: Ohio and Kansas.

“According to documents in the NAACP Papers, from the time of the film's first release until the end of 1931, the following governmental actions were taken either to ban the film or to cut it; some of these actions pertained to re-issues of the film, including the 1930 version with an added soundtrack: In Alaska, on 8 Oct 1918, the mayor of Juneau stopped the showing of the film; in California, in Jun 1921, the film was taken off the market, and in 1922, it was prohibited from exhibition by an ordinance passed by the City Council of Sacramento; in Connecticut, in Dec 1915 in New Haven, substantial cuts were made, on 21 Aug 1924, the exhibition of the film was canceled in New Britain, and in Mar 1925, the mayor of Hartford ordered two theaters to show another picture instead; in Illinois, on 15 May 1915, the mayor of Chicago refused to permit a license for the film; in Indiana, in Sep 1915, the film was banned in Gary; in Kansas, in Jan 1916, the film was banned; in Kentucky, on 20 Nov 1918, the mayor of Louisville stopped the exhibition of the film using an executive order; in Massachusetts, in 1915 in Boston, the rape scene involving "Gus" was nearly all cut out, in May 1921, the mayor of Boston suspended the license of a theater owner who planned to show the film, and in Jul 1924, in West Newton, the mayor made a request to a theater not to show the film; in Michigan, on 14 Feb 1931, the mayor of Detroit issued an order prohibiting the film's exhibition; in Minnesota, in Aug 1921, the mayor of Minneapolis refused to allow its exhibition, and on 30 Dec 1930, the City Council of St. Paul passed a resolution ordering the chief of police to stop the film's exhibition; in Nebraska, on 30 Mar 1931, the mayor of Omaha prohibited the showing of the film; in New Jersey, on 15 Dec 1923, the film was withdrawn in Camden, in Jul 1924, the Board of Commissioners of Montclair passed a resolution directing that the film not be shown, in Nov 1931, officials in Roselle deleted portions of the film, and on 4 Sep 1931, the deputy director of public safety in Jersey City forbid a theater from continuing to exhibit the film; in New York, on 13 Oct 1931, the mayor of Glen Cove, Long Island stopped the showing of the film; in Ohio, in Oct 1916, the film was banned, on 2 Jun 1925, the Supreme Court refused to license the film in the state, and on 4 Mar 1926, the attorney general ruled that the Ku Klux Klan could not show the film privately; in Oregon, in Mar 1931, the city council of Portland prohibited the showing; in Pennsylvania, on 2 Sep 1931, the mayor of Philadelphia ordered the film barred from the screen; in Rhode Island, in Sep 1915, the police commissioner of Providence refused to give the producers a license to show the film; and in West Virginia, in Feb 1919, the legislature passed a bill barring the film from the state. Many of these actions came in response to protests organized by local branches of the NAACP, which also organized protests in other jurisdictions. Protests also occurred in the cities of Morristown, NJ, Norfolk, VA, Springfield, IL, Vancouver, Canada, Atlanta, Atlantic City, Baltimore, Cleveland, Dallas, Milwaukee, Nashville, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, San Francisco, Spokane and Toronto” (AFI Catalog).

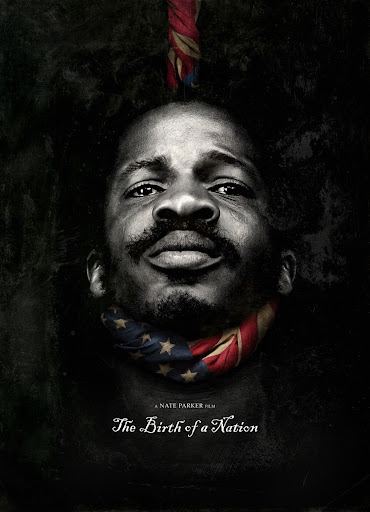

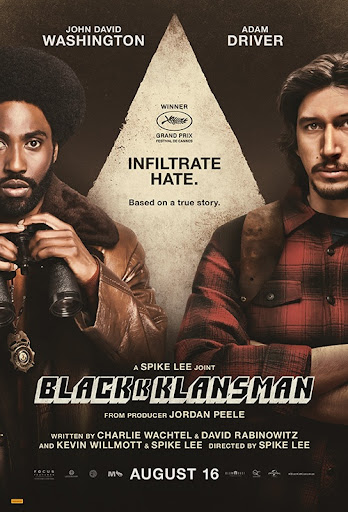

In the 100 years since its debut, the film has consistently been a lightning rod for debate. It has been trotted out as a symbol of American values, whether positive or negative, at every critical juncture: the boycotts of the Civil Rights era, the race riots of the 1990s, Barack Obama's election, and even the #BlackLivesMatter protests. As the African-American community attempts to reclaim the narrative with films like BlacKkKlansman (2018) or Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation (2016), the desire to grapple with the "dark side of wrong" prevails.

Poster for The Birth of a Nation (2015).

Poster for BlacKKKlansman (2018).

The outcry surrounding The Birth of a Nation may have been delayed, but it certainly won’t be reduced to a whimper anytime soon. Whether for its cinematic achievement or its bigoted content, the film is a perennial response to current events.

“In the year 2024 the most important single thing which the cinema will have helped in a large way to accomplish will be that of eliminating from the face of the civilized world all armed conflict. Pictures will be the most powerful factor in bringing about this condition. WIth the use of the universal language of moving pictures the true meaning of the brotherhood of man will have been established throughout the earth. For example, the Englishman will have learned that the soul of the Japanese is, essentially, the same as his own. The Frenchman will realize that the American’s ideals are his ideals. All men are created equal” – D.W. Griffith, “The Movies 100 Years From Now” (1924).

Resources