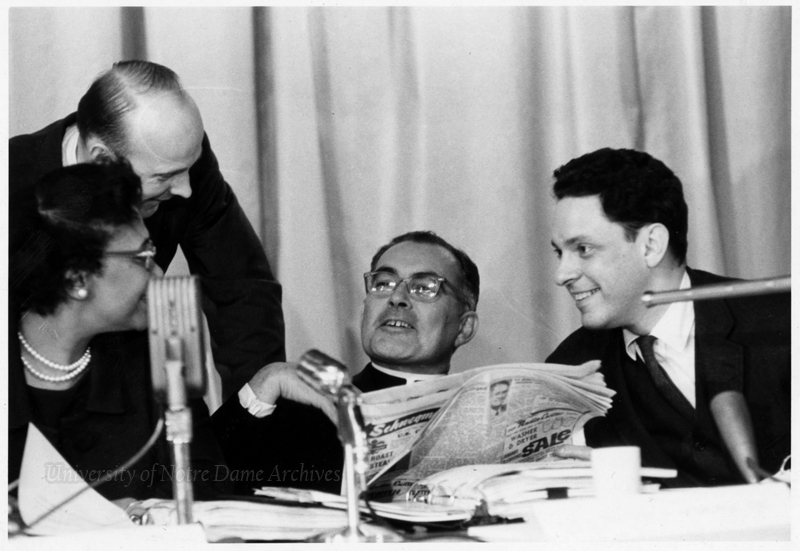

The Commission had 2 years to investigate one specific area of civil rights violations: voting, and then recommend corrections. They started in Montgomery, Alabama, the site of the most complaints.

The resistance from Southern officials made the investigation difficult, but the Commission made their way across the South and North looking at discrimination claims.

"Don't give me any theological stuff, I know what the Bible says, I try to be a Christian, but I'm an old dog."

- John Battle to Father Hesburgh