The Strike

[Group of mainly female shirtwaist workers on strike, in a room, New York], 1910, Library of Congress.

The Causes

In the early 1900s, working conditions were deplorable, especially in factories in the shirtwaist, or blouse, hub of New York. The workers were mostly Jewish women from Eastern Europe. They worked 14 hour workdays making only two dollars a day before their pay was docked for used materials. Pauline Newman, a labor activist and former factory worker, detailed her time at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, a factory known for its poor working conditions and eventual fire, in an autobiographical letter:

“As you will note, the days were long and the wages low -- my starting wage was just one dollar and a half a week -- a long week -- consisting more often than not, of seven days. Especially was this true during the season, which in those days were longer than they are now. I will never forget the sign which on Saturday afternoons was posted on the wall near the elevator stating -- ‘if you don't come in on Sunday you need not come in on Monday’!”

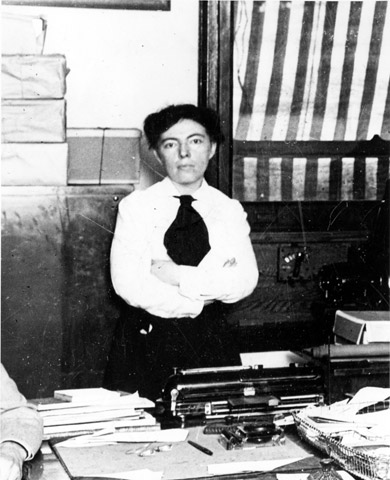

Pauline Newman, 1910, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Long workdays and little pay paired with poor ventilation and locked doors to prevent theft led workers from hundreds of factories to strike on November 22, 1909, prompted by the 23-year-old Ukrainian immigrant worker Clara Lemlich’s passionate words, spoken in Yiddish:

Clara Lemlich, 1910, Jewish Women's Archive.

“I am a working girl, one of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here to decide is whether we shall or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared—now.”

-Clara Lemlich

General strike: A strike all industries participate in—activity in the city will grind to a halt.

The Uprising

On November 23, 1909, 15,000 workers from various factories walked away from their jobs. By the end of the day, there were 20,000 workers on strike, earning it the name “Uprising of the 20,000.”

Towards the beginning of the strike, conditions looked grim. The women faced violence from anti-union factory owners, namely Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, owners of the Asch building of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. Blanck and Harris bribed prostitutes, fighters, and police officers to harass, abuse, and arrest the strikers. Lemlich was among the women harmed, receiving six broken ribs. Court and bail fees ran into the thousands.

Blanck and Harris were Jewish immigrants themselves, as Amy Kolen, whose grandmother was a cousin of Harris, states in her retelling of factory conditions:

“Themselves refugees from Russia, Harris and Blanck exploited the immigrants who worked for them through a subcontracting system common in the industry at the time . . . The firm's owners felt no responsibility for the workers, and never knew exactly how many employees they had because only the contractors' names were listed on the payroll. It was the contractor who, on Saturdays, paid the workers. (Other similar shops were closed on Saturday afternoons but Harris and Blanck had managed to ignore the union's demand for a five-and-a-half-day work week.) There was no starting salary—though the pay was reportedly no lower than at other shops—and little chance of a raise.”

-Amy Kolen

Strikers also endured a frigid winter. A song from the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) details the conditions on the picket line:

In the black of the winter of nineteen nine,

When we froze and bled on the picket line,

We showed the world that women could fight

And we rose and won with women's might.

Chorus:

Hail the waistmakers of nineteen nine,

Making their stand on the picket line,

Breaking the power of those who reign,

Pointing the way, smashing the chain.

And we gave new courage to the men

Who carried on in nineteen ten

And shoulder to shoulder we'll win through,

Led by the I.L.G.W.U.

The Uprising of the Twenty Thousand (Dedicated to the Waistmakers of 1909), Cornell University, 1909.

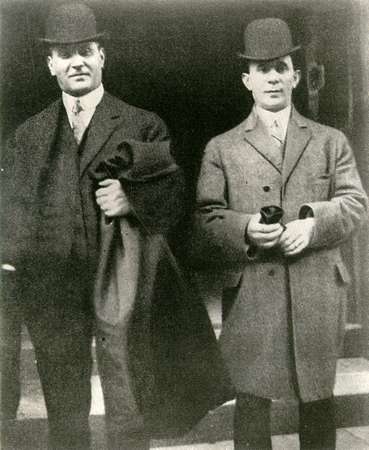

Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, 1910, Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Along with the weather, the strikers were making little ground in their negotiations. Despite their numbers, they got little to no media coverage, so factories were in no rush to meet their demands. However, a group of wealthy women mockingly dubbed the “mink brigade” put a stop to that. Women like Mary Drier, Alva Belmont, and Anne Morgan bailed women out of jail, paid for food, court fees, and rent, and even picketed with them. Because of their high social class, the media started to pay attention, and strikers were less likely to be harmed with a “lady” on the line. Rose Schneiderman, one of the strike’s leaders, detailed the help the mink brigade offered, writing,

“An ally of great value to us was 'The Mink Brigade,' a group of wealthy women who marched on the picket line with the strikers during the Shirtwaist Makers' Strike and several times afterward. They lent prestige and, more important, an aura of respectability to our demonstrations. This was most important for it helped to weaken the attempts of the unsympathetic to force the women back to work through prison sentences and physical violence."

-Rose Schneiderman

Rose Schneiderman, 1910, Jewish Women's Archive.

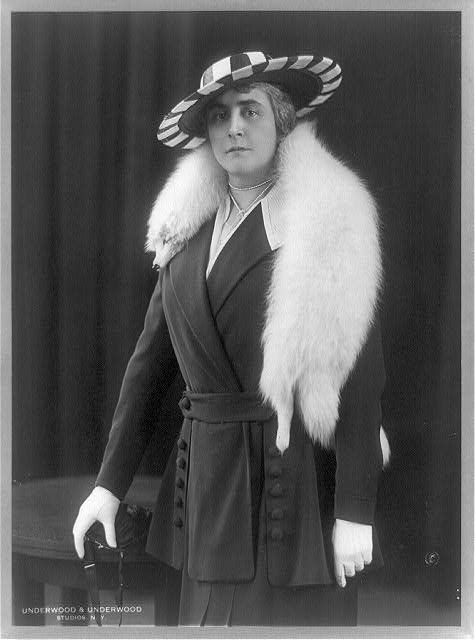

Anne Morgan, 1915, Library of Congress.

With the media’s involvement, smaller factories began to grant the striker’s demands: a 52-hour workweek, wage negotiations, use of material without fines, and even their biggest demand: a closed, union only shop. The larger factories, including Triangle, formed The Associated Waist and Dress Manufacturers, refusing to give in to a closed shop. The factories did not want to be forced into hiring only union members. The workers remained on the picket lines. However, they could not picket forever. Worried about the union’s connection with socialism, Anne Morgan slowed her support for the strike, and pressure from the media went with her. The uprising ended February 15, 1910, and strikers returned to their factories.

“What drove people like Isaac Harris to exploit their fellow immigrants, fellow Jews who, like themselves, had fled from tyranny in their homeland to a life that promised, as Grandma said in her letters, streets paved with gold?”

-Amy Kolen