Mexican territory ceded to the United States in 1845-1853.

"The ancestors of many of these people had lived in the same area since before the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth--and yet the rest of the U.S. population often regarded them as aliens, people who were not as competent, not as socially acceptable, and generally unequal to Anglo-Americans. As a result, Mexican-Americans have endured long years of discrimination, racism, and oppression."

- Jose Limon, Professor at University of Texas, "A Name of Their Own: Chicanos.", 2005.

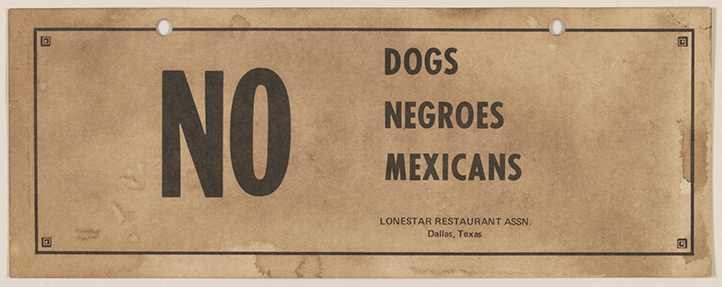

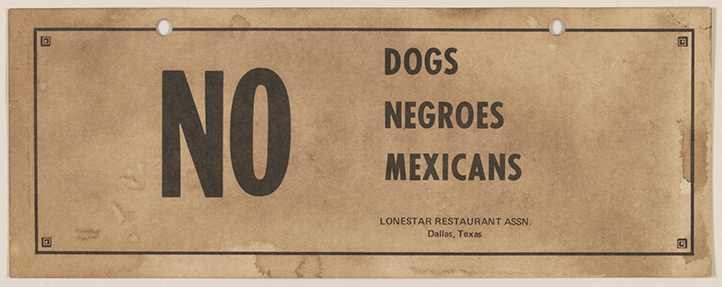

"NO DOGS, NEGROES, MEXICANS.” Lonestar Restaurant Association, Dallas, Texas. 1960s.

"We Serve White's only No Spanish or Mexicans". 1960s. Russell Lee Photography Collection.

In order to understand the Mexican-American experience, it must be traced back to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in which Mexico ceded land to the United States. This marks the beginning of discrimination, racism, and identity crisis that shaped Mexican-American life. Mexican-American history, prior to the Chicano movement, consisted of marginalization and attempting to assimilate into American society. Although there was push back against discrimination, there was no large-scale movement to mobilize the Mexican-American community.

"The wall could represent just about anything you want it to represent. People escaping from something or breaking tradition or just coming out of what's always been there, always compressed, always hidden. The writing was incorporated or included in the whole piece to keep it here so it would just remain part of the barrio and part of everything that is here period."

- Willie Herron, Chicano artist, interview The Wall that Cracked Open. 1973.

Herrón, Willie. "The Wall That Cracked Open, 1972." (2008).

Chaz Bojórquez, Arroyo Seco River, Los Angeles, 1973. Photo: Gusmano Cesaretti.

Chaz Bojórquez’s first Señor Suerte tag, Harbor Freeway, Los Angeles, 1969.

"The Chicano gangs were originally more about taking pride in a neighborhood. By 1943, when the LA riots happened against the Latino zoot suiters, it created the foundations for the Cholo culture. Graffiti was a way to define your identity[...]Placas are usually placed at the edge of a neighborhood, marking the territory for an individual gang. It says, “This is ours.” When I see a tag, I see a complaint; I see a whole bunch of tags, I see a petition."

- Chaz Bojorquez, Chicano graffiti artist, "Cholo Graffiti.", 2011.

It was in barrios, segregated communities for Mexican-Americans, that the Chicano art style began to develop as well as a brewing sense of displacement in American society. However, it was not until the Chicano Movement that Mexican-American culture, history, and art were defined by a collective identity along with a call to action for social justice.

Leffler, Warren K. Civil rights march on Washington, D.C. Library of Congress.

“During the turbulent period of protest which characterized the 1960s and early 1970s, Mexican-Americans joined Blacks, women, and other disadvantaged groups in their attempt to establish unity and demand their share of the American Dream.”

- John Hammerback and Richard Jensen

Chicanos also drew from the Black Freedom Movement that inspired social and political change in the 1960s. Mexican-Americans began to embrace the idea of Chicanismo, reclaiming the term "Chicano", an identity of one who is aware of social injustice and educated on Mexican-American history and culture.

Rivera, Diego. Pan American Unity. 1940.

“The civil rights movement of the 60s informing minorities to find out more about their origins, about their roots and to check things out more clearly to get the truth on everything. When the Chicano Movement, which actually started around that time as well, starts to check out their history, they recognize the great Mexican muralist and that was something that inspired them to think that: we can do murals, we can do wall paintings too.”

-Susan Cervantes, founder and director of Precita Eyes Muralists, Telephone interview, 2021.

"Tres Grandes" - David Alfaro Siqueiros, Jose Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera.

Early Chicano murals were a way of drawing from Mexican culture, which was a theme of the movement because of their embracing of non-Anglo history and romanticization of Latin heritage. Diego Rivera, a very famous Mexican muralist, often painted heavily social/political imagery in his murals.

"The artists also aligned their identity with the political activism of Mexican political muralists such as Jose Clemente Orozco, David Siquieros and Diego Rivera."

- Michelle Kern, Professor at College of San Mateo "Artist, teacher, Chicano activist, Jose Montoya made history." People's World, 2013.

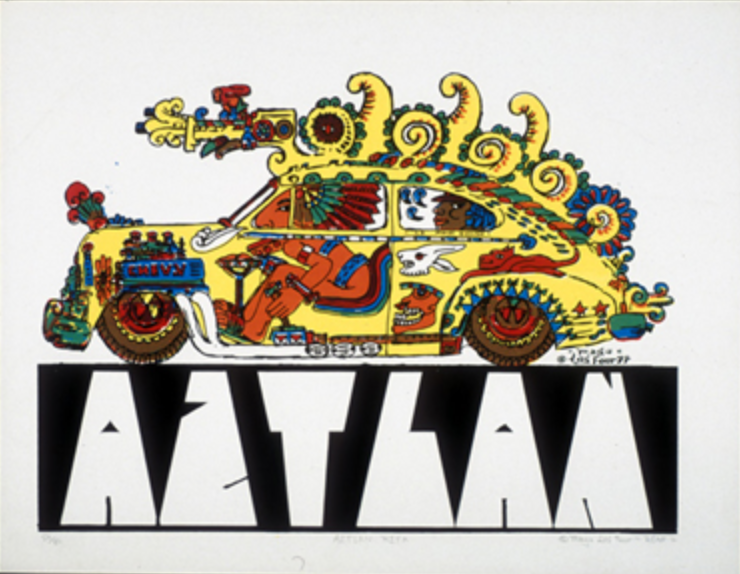

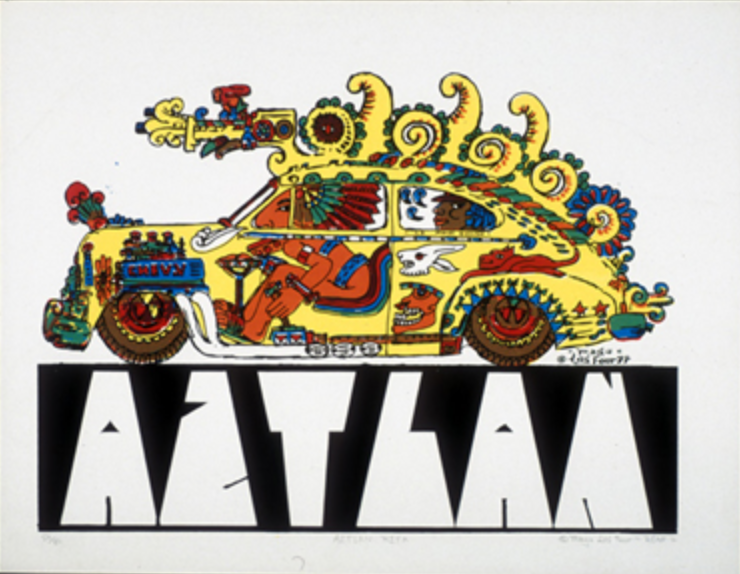

Lujan, Gilbert"Magu." See You In Aztlan. 1977. silkscreen print, Online Archive of California.

"What's interesting is how did the plan actually affect people as they really began to take to the streets or create organizations or do art work or educate[...] It was a watershed moment in Chicano or early civil rights activism that gave a plan for how to proceed in social change and to achieve social justice."

- Sybil Venegas, Chicana/o Studies professor at East Los Angeles College, "The Manifesto.", 2011.

"A big part of this whole Chicanx identity is this idea of Aztlan. You will hear this a lot when you google the Chicano movement or Chicanx identity Aztlan will come up. Aztlan is very interesting and complicated. It is basically this claim that there are certain parts of what is now called US that belong to Chicanos, Chicanas, Chicanx people and to their indigenous ancestors because as Chicanx people our connection to our indigenous roots can be traced to Aztec people primarily or Mechica. This Aztlan territory was supposedly Mexico before the Treaty of Guadalupe. It’s places like California, Arizona, New Mexico and that southern area. What I understood throughout the years is that folx within the Chicano movement have believed that one day that land will be for Chicanos again and the borders won’t be there. [...] All those states that I just mentioned that are supposed to be Aztlan, that already had indigenous people before. There were indigenous tribes, indigenous communities all throughout these states, all throughout what is called “Aztlan” that are not being represented or talked about at all within this idea, this mythology that this is Aztlan."

- Samara Almonte, "New Series! Beyond Chicanismo: Indigeneity & the Environment." Raices Verdes, 2020.

The Plan of Aztlan was constructed at the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference and, for the first time, presented a set ideology and goals for revitalizing the Chicano community into a nationalist movement.

"We are a bronze people with a bronze culture. Before the world, before all of North America, before all our brothers in the bronze continent, we are a nation, we are a union of free pueblos, we are Aztlán." - National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference (1969). El Plan de Aztlán. Denver, Colorado.

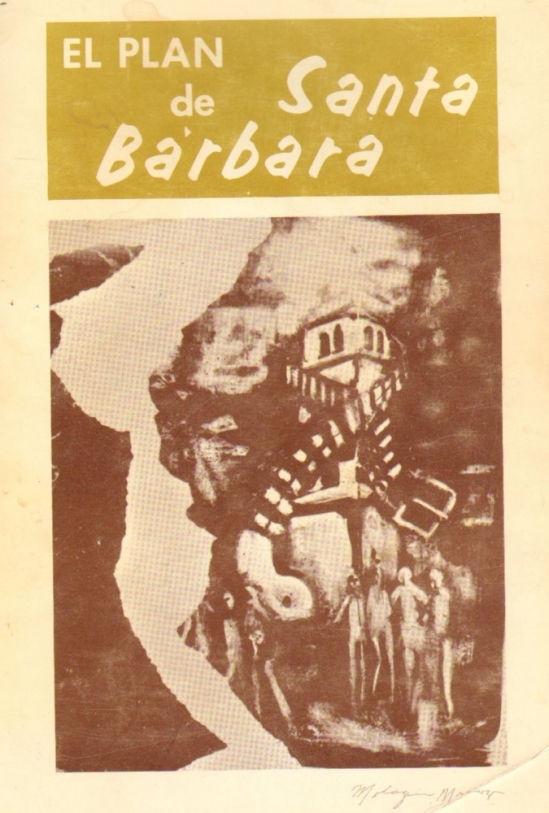

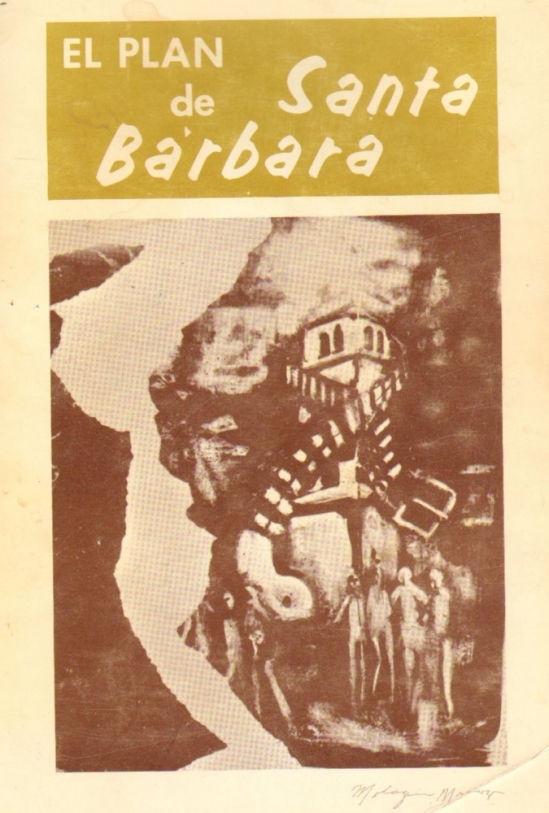

Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education. El Plan de Santa Barbara: A Chicano plan for higher education. 1971. La Causa Publications.

"There’s this focus primarily on Aztec culture, Aztec mythology, Mechica mythology and sometimes even Mayan as well. I am sure that there are people with our movement that have identified as such. There are definitely people that have Aztec ancestry, Mayan ancestry, Mechica ancestry but not all of us do. [...] It has pushed this narrative for all of us to kind of take on some of this knowledge from the Aztec and Mechica people. Which in a way is problematic because that doesn’t belong to all of us and that isn’t part of all of our history."

- Samara Almonte, "New Series! Beyond Chicanismo: Indigeneity & the Environment." Raices Verdes, 2020.

In their goals for cultural affirmation and political activism, the plans emphasized public artwork as a vehicle for delivering ideological and political messages. However, El Plan de Aztlán, and another El Plan de Santa Barbara, written by male Chicano leaders, lacked Chicana, Queer, and Indigenous voices.

In many ways the climate demanded a movement. Artists became activists and joined leaders of the Chicano movement to create a visual form of protest.

“You have a population that was really ready for a movement that acknowledged who they were, and in many ways demanded to be who they were. The time was right, the setting was right and it was an amazing time for this community to assert its presence."

-Sybil Venegas, Chicana/o Studies professor at East Los Angeles College, "The Manifesto.", 2011.