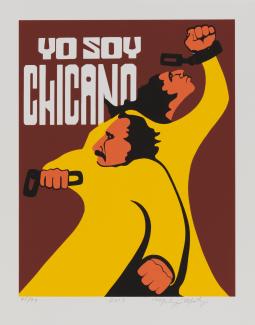

"Words weren’t the only way that people communicate. We can communicate through visual images and through oral traditions as well."

~ Katynka Martinez, Chicana/o Studies professor at San Francisco State University, Videoconference interview, 2021.

A nonviolent form of protest, the murals and posters of the Chicano art movement worked to inspire and educate not only a Mexican-American audience but also all members of the community.

Baca, Judy. La Memoria De Nuestra Tierra: California. 1996. Univerity of Southern California.

"The arts also play a major role in the Movement. As cultural pride blossomed, Chicano visual arts, music, literature, dance, theater, and other forms of expression also flourished, and a full-scale Chicano Art Movement emerged during the early years of the Movement. Chicanos expressed their cultural heritage through painting, drawing, sculpture, and lithography"

~ Jose E. Limon, Professor at Univeristy of Texas, "A Name of Their Own: Chicanos.", 2005.