Source: Keenan, JP. 17 Jan. 2017.

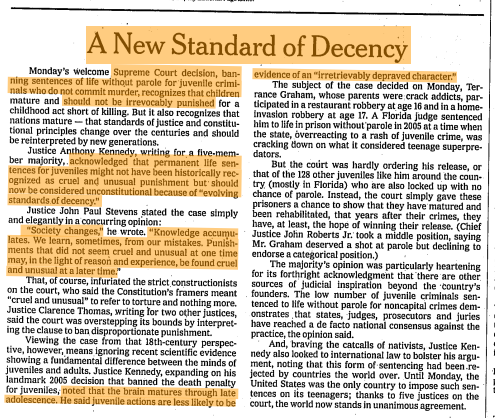

""A New Standard of Decency," the New York Times, 2010

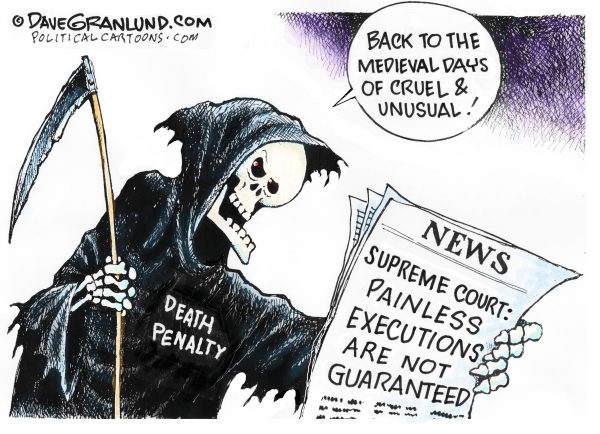

As a society grows and changes, and more factual evidence is uncovered, it is only natural that the standards of ethicality in a society would also evolve. The juvenile death penalty was thought at one point to be perfectly acceptable, but as society's understanding of the undeveloped human brain changed, so did the attitude towards the juvenile death penalty.

"Viewing the case from that 18th-century perspective, however, means ignoring recent scientific evidence showing a fundamental difference between the minds of juveniles and adults."

- "A New Standard of Decency," the New York Times, 2010

“When the California Supreme Court ruled, in 1972, that the death penalty was unconstitutional, the Chief Justice, in his opinion, appealed to 'evolving standards of decency.'”

- David Garland, 2011

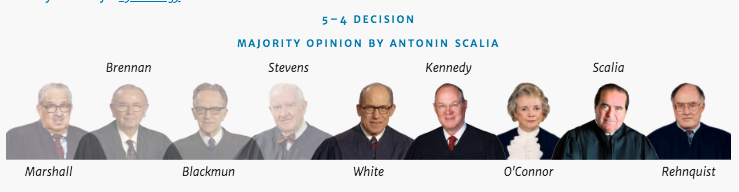

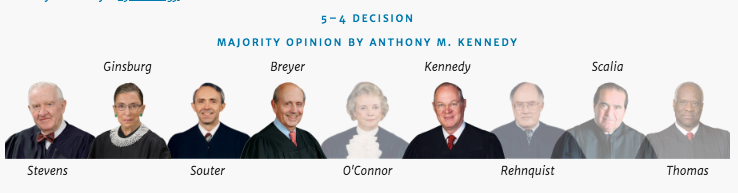

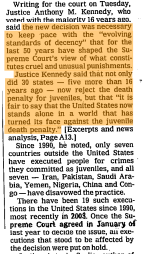

Greenhouse, Linda. "SUPREME COURT, 5-4, FORBIDS EXECUTION IN JUVENILE CRIME: RETREAT FROM '89 RULING, CITING 'EVOLVING STANDARDS,' AFFECTS 72 ON DEATH ROW." New York Times

“Furman’s attorneys famously linked the Fourteenth and Eighth Amendments together to argue that the intrusion of the biopolitical politics of life into capital punishment… despite the statutory presence of the death penalty, capital punishment was itself contrary to ‘evolving standards of decency.' The reason the death penalty persisted, they argued, was that it was so rarely imposed.”

- David Garland, 2011