Carrying the Burden: Labor Rights and Civic Responsibilities in the Memphis Sanitation Strike

Historical Context

Background:

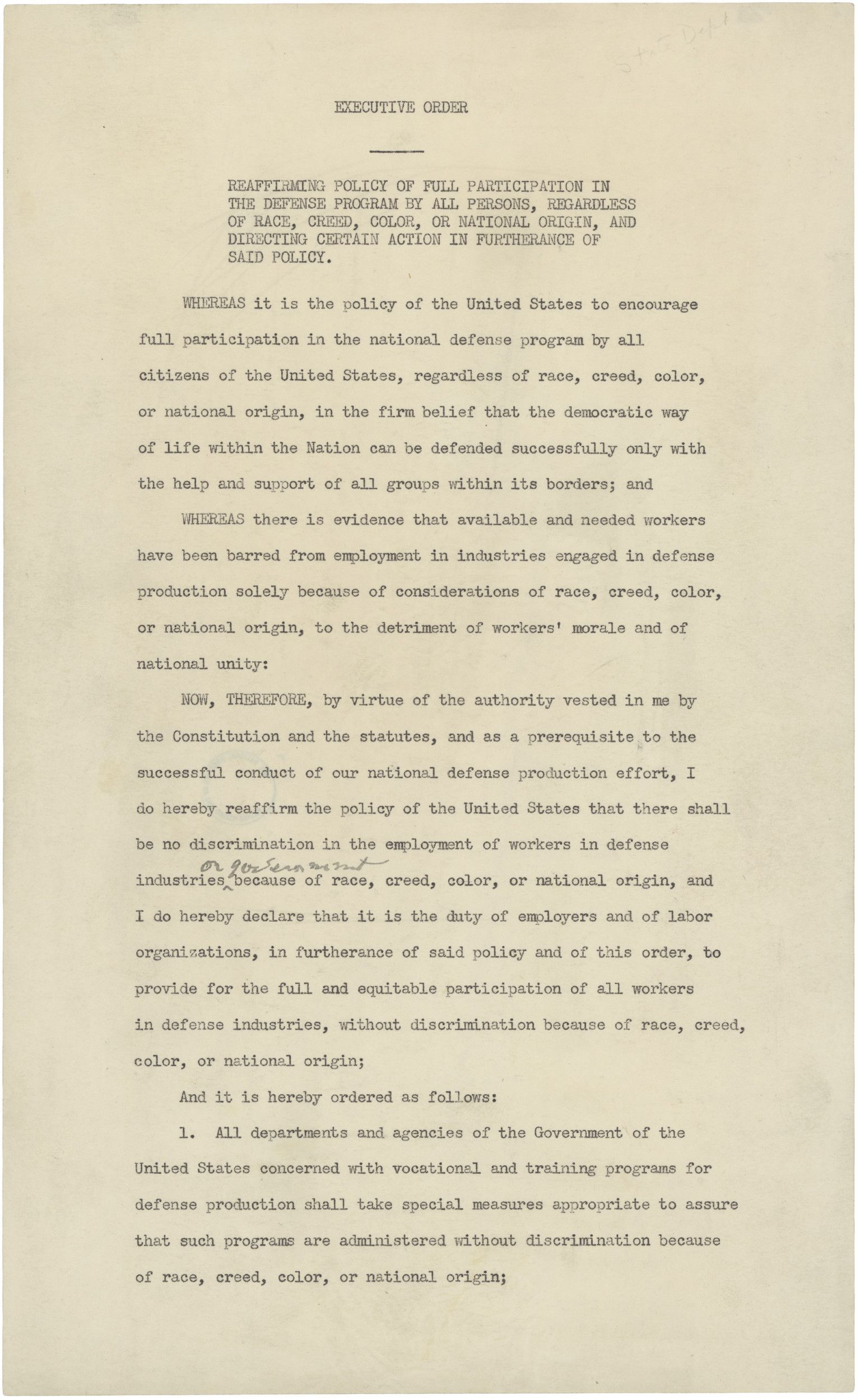

In the 1960s, Memphis, Tennessee, was a city consumed by racism and economic disparity. As the ideas of Dr. Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement started to gain momentum, the fight to bring about racial justice intensified, and the disparities of African American workers in the economy became starkly apparent. Earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 8802 in 1941 which made significant strides towards ending racial discrimination in the defense industry, but other sectors such as municipal services remained resistant to integration and equal treatment.

Cordell, Gina, and Patrick O’Daniel. The Memphis Country Club. Photograph. Historic Photos of Memphis. 1st ed. Memphis, Tennessee: Turner, 2006. Memphis.

Cordell, Gina, and Patrick O’Daniel. The Colored Old Folks Home. Photograph. Historic Photos of Memphis. 1st ed. Memphis, Tennessee: Turner, 2006. Memphis.

“Executive Order 8802 to Prohibit Discrimination in the Defense Industry.” General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/executive-order-8802.

"I do hereby reaffirm the policy of the United States that there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin, and I do hereby declare that it is the duty of employers and of labor organizations, in furtherance of said policy and of this order, to provide for the full and equitable participation of all workers in defense industries, without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin." Executive Order 8802, 1941

Henry Loeb was elected as mayor of Memphis in January 1968, and soon tensions between the city administration and black sanitation workers began to increase.

"[. . .] the new government had renewed Mayor Henry Loeb’s old policies from his days as Public Works Commissioner in the 1950s: when it rained hard, DPW dismissed workers for the day, with only two hours’ worth of pay [. . .] this policy meant many lost days of work shrank their already-meager wages." Maxine Smith, Michael K. Honey, University of Washington, Going Down Jericho Road, 2007

“Henry Loeb - Alchetron, the Free Social Encyclopedia.” Alchetron.com, 1 October 2024, https://alchetron.com/Henry-Loeb.

Conditions:

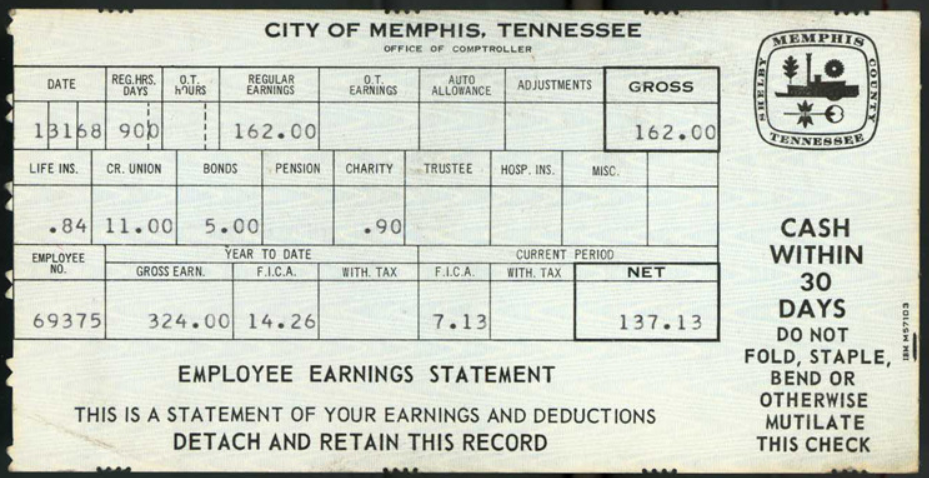

Sanitation workers were forced to labor under poor and unsafe working conditions, including working overtime and night shifts during inclement weather in dilapidated garbage trucks. Black workers were often paid less than their white counterparts for the same work which was as dangerous and as demanding, and their demands for better treatment were consistently ignored by city officials.

“Sanitation workers earned wages so low that many were on welfare and hundreds relied on food stamps to feed their families.” Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike, 1968. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

"At day's end the Black garbagemen would be covered with stinking slime. The White drivers had showers. There were no showers for the men in the back of the truck."

"Surviving Memphis Sanitation Workers from 1968 Strike Awarded $70k Grants Sunday." TODAY.

Pay check stub from sanitation worker. Photograph. I AM A MAN. Memphis, 1968. Memphis. https://projects.lib.wayne.edu/iamaman/items/show/146.

“ We just aren’t heard. We have been down for the same number of years hollering about police brutality. Nobody listens to us and the garbage men through the years. For some reason, our city government demands a crisis […] They seem not to hear Black people […] We are invisible.” Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike, 1968. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

“Sanitation workers inspect a garbage truck similar to the one in which two workers were killed on Feb. 1, 1968. Preservation and Special Collections Department, University Libraries, University of Memphis. Accessed at https://mlk50.com/memphis-had-another-shameful-tragedy in-1968-it-could-have-been-avoided-ef828f0f5091.

Tensions came to a head on February 1, 1968, when two Memphis garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were killed by a jammed garbage truck compactor. The dilapidated truck had been reported months ago, but to save money on the orders of the Mayor, they continued using the hazardous trucks.

"A lot of men that worked in that particular area said they felt it was a disgrace and a sin, that they shouldn’t have continued to use that particular piece of equipment."

T. O. Jones, a fired sanitation worker and strike organizer, 1968

Fleischer, Mark. “Garbage Truck Kills 2 Crewmen.” Storyboard Memphis. February 1, 2018. Accessed at https://storyboardmemphis.org/history/garbage-truck-kills-2-crewmen/.

"It was horrible. He was standing there on the end of the truck, and suddenly it looked like the big thing [the compression unit] just swallowed him. He was standing on the side and the machine was moving. His body went first and his legs were hanging out. I didn't know at the time someone else had already been crushed in the thing."

Mrs. C. E. Hinson, witness, Press Scitimar, 1968