"At our meetings, each one of them took a different route through the darkness to the indicated rendezvous." ~ Achard de Bonvouloir’s report, in Doniol, I, 287

The Secret Rendezvous:

Reshuffling Europe’s

Diplomatic Cards

Philadelphia, December 18, 1775. A mysterious French envoy, Achard de Bonvouloir, met secretly with Benjamin Franklin and members of the Continental Congress' foreign relations committee.

Vergennes’ approach

The mastermind behind this rendezvous was Comte de Vergennes, an experienced French diplomat, now King Louis XVI's foreign secretary.

Mortified by France’s humiliation in the Seven Years War, Vergennes wanted to restore France’s prestige and weaken its imperial rival, Britain.

He welcomed America’s rebellion as an opportunity for revenge.

“England is the Monster against which it is wise to be always prepared. [...]

Let us profit by their mistakes. The English have inconsiderately embarked on a war with their American colonies, which, from now on, will cost them very dear and which as a consequence, might very easily cost them part of their commercial existence.”

~ Comte de Vergennes to Marquis d'Ossun, July 28, 1775, in Meng, 340-341

Charles Gravier Comte de Vergennes by Vincezo Vangelisti, courtesy of British Museum

Vergennes organized Bonvouloir’s secret mission to make overtures to Americans.

“Canada is the sore point for them and they must understand that we do not think about it at all and that rather than envying them their liberty and independence that they are working to acquire, we admire on the contrary the grandeur and nobility of their efforts and that, without interest in harming them, we shall with pleasure see those happy circumstances that allow them to frequent our ports; the facilities that they will find there for their trade will soon prove to them the esteem we have for them.”

~ Comte de Vergennes, French Minister of Foreign Affairs, to Count de Guines, Ambassador to Great Britain, August 7, 1775, Naval Documents of the American Revolution

America’s response

Vergennes’ reassurances were needed. France, often allied to Indian tribes, had been the colonists’ traditional enemy.

But Americans, rebelling against Britain, now had their Congress and army.

Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor, courtesy of Library of Congress

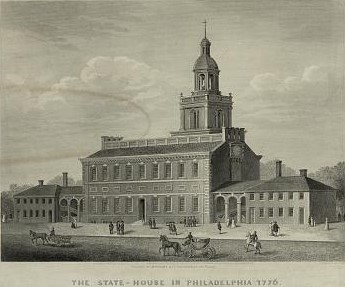

The State House in Philadelphia in 1776 by John Serz, courtesy of Library of Congress

Still, victory required foreign aid. Resentment of England united France and America; the colonists agreed to meet Bonvouloir.

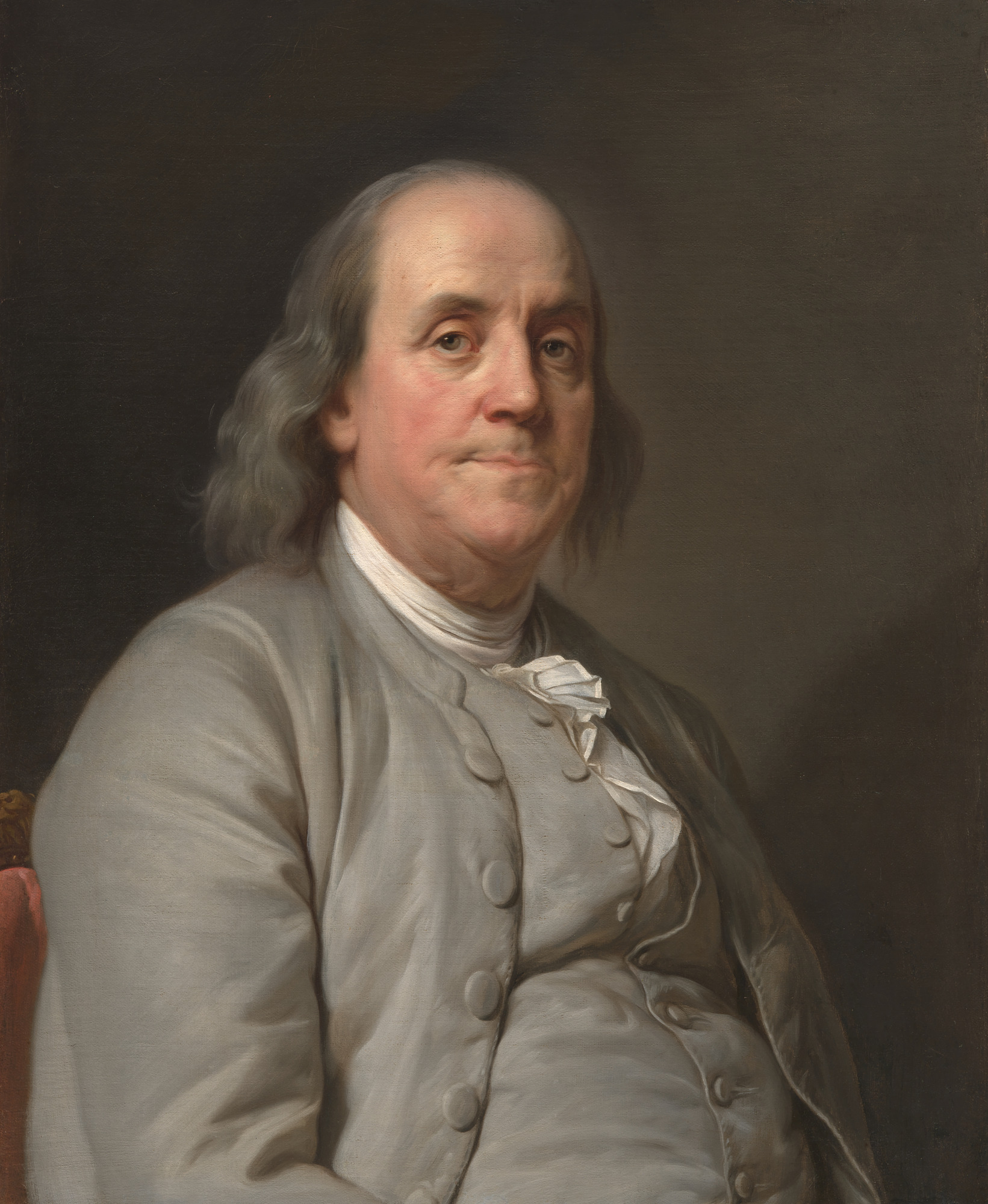

Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Duplessis, c. 1785, courtesy of National Portrait Gallery

With his fame and experience as colonial agent in London, Benjamin Franklin, now a Pennsylvania delegate, was best fitted for this secret – indeed, treasonous –meeting.