Fighting For Miscegenation - How the Loving v. Virginia Case Changed Marriage Laws Across the U.S.

The Supreme Court Case

Before the Case

Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving were family friends. They fell in love and were high school sweethearts. This wasn't seen as a big deal because their community, Central Point in Caroline County, Virginia, was small and racially diverse. However, Mildred and Richard couldn't wed in Virginia because of the state's anti-miscegenation legislation. So on June 2, 1958, Mildred and Richard got married in Washington D.C. before returning to Virginia. On July 14, 1958, they were arrested by the local sheriff and accused of breaking Virginia's anti-miscegenation law.

The Lovings were indicted on those charges. After they pleaded guilty the following year, Judge Leon M. Bazile sentenced the Lovings to one year in prison. However, he suspended the sentence on the condition that they would leave Virginia and not return together for 25 years. Following the sentencing, the Lovings moved to Washington D.C., and raised their family there for several years.

Grey Villet, 1970s, Richard and Mildred with their children, Icarus Films

Start of the Case

In 1963, Mildred Loving requested help from U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy so they could end their sentence and return to Virginia since both the Lovings desired to return to their hometown.

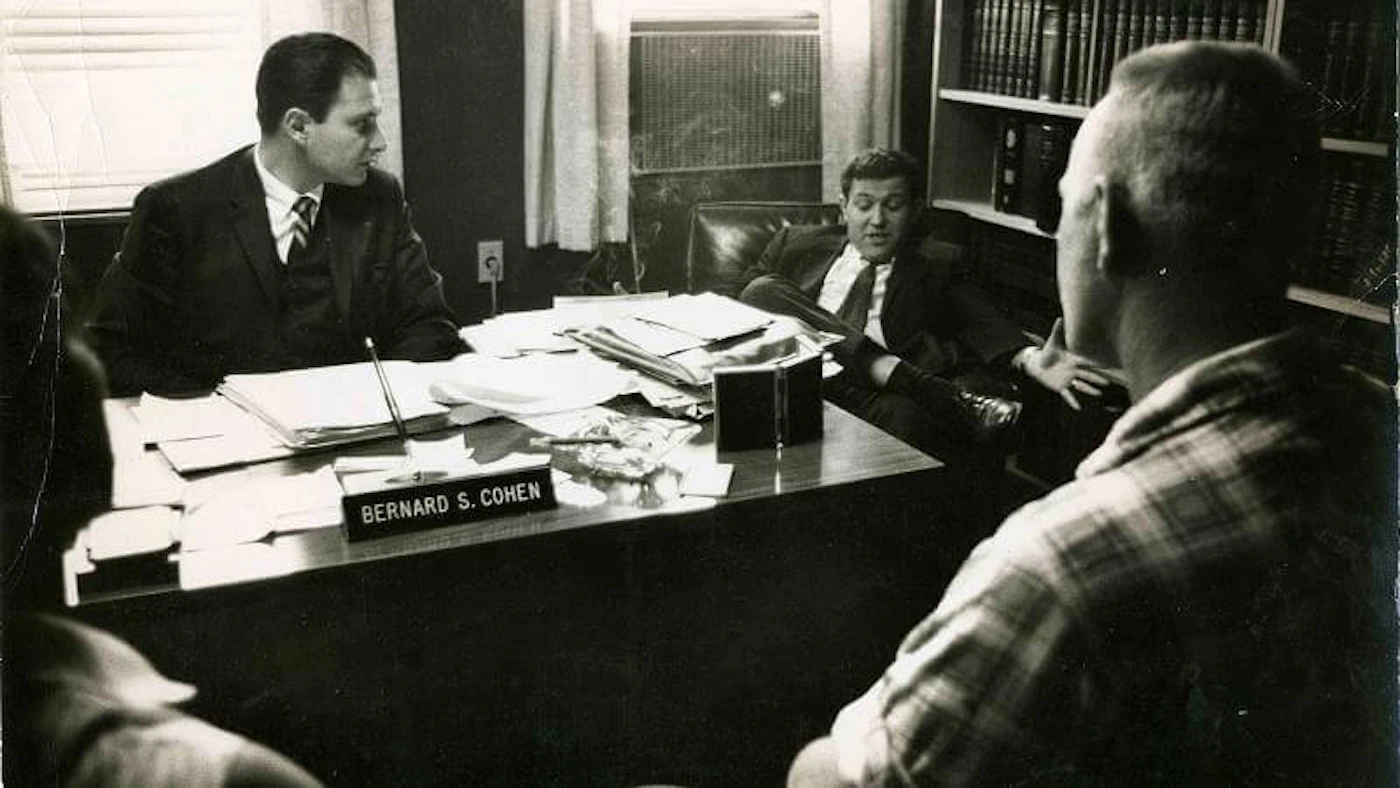

He referred the Lovings to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which accepted the Lovings' case. The ACLU assigned Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop to assist the Lovings. With their help, the Lovings filed a motion against Judge Leon M. Bazile asking him to vacate their conviction. Judge Bazile didn't sustain their appeal, so they took it to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. The appeal wasn't sustained by them either, so in April 1967, it was brought to the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Grey Villet, Bernard Cohen meeting with the Lovings before the Supreme Court Case, HBO

The Case

The state's main argument for not overturning the Lovings' sentence was that, under the 10th Amendment, marriage was within state authority and should remain so without intervention from the federal government. They claimed that as a state, they had the power to continue enforcing the punishment because they had chosen to impose it. In terms of the statute's validity, the Commonwealth declared that it didn't count as racial discrimination because it upheld the law by punishing both whites and blacks equally.

The Lovings countered that the “interracial” marriage law applied only to white-black marriages, not to interracial marriages between people of color, and that supported white supremacy, henceforth racism. They argued that the overall basis on which the interracial marriage law rested was based on biased ideals, lacking evidence as to why it was still necessary. The state's claim was dismissed because it wasn't strong.

The Lovings’ brought up their main argument, that Virginia’s interracial marriage law continued to be unconstitutional because it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Equal Protection Clause stated that:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Their lawyers stated, despite being of different races, both the Lovings were U.S. citizens, and as citizens, marriage was a privilege that they held. The state did not reserve the right to violate it in any case.

“To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law ... Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the state,” - Chief Justice Earl Warren

The court was in unanimous agreement with the Lovings. So on June 12, 1967, the frontier in interracial marriage rights was crossed after the Supreme Court banned all anti-miscegenation statutes within the U.S. and overturned the Lovings’ previous sentence.

Miscegenation in the U.S.

Aftermath