Abolishment of the Edo Feudal Hierarchy:

The Successes and Consequences for Japan

Legacy

The short-term impact of abolishing the Edo feudal system exemplified the extent to which Japan evolved throughout the 19th century. Their warlike approach to handling dissension initially resulted in more consequences than benefits. All parties, including the Tokugawa shogunate, the Meiji government, and the rebelling samurai, faced equally adverse outcomes regarding the number of Japanese citizens left dead or impoverished from war—something that remained constant on all sides.

“Battle of Shiroyama." Samurai: The World of the Warrior, circa 1800s

"You can see that there is not much chance for the Rebels to escape, and when their food is gone they will have to give in [to the imperialists] and end the rebellion."

~ John Capen Hubbard, a ship captain who witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Shiroyama

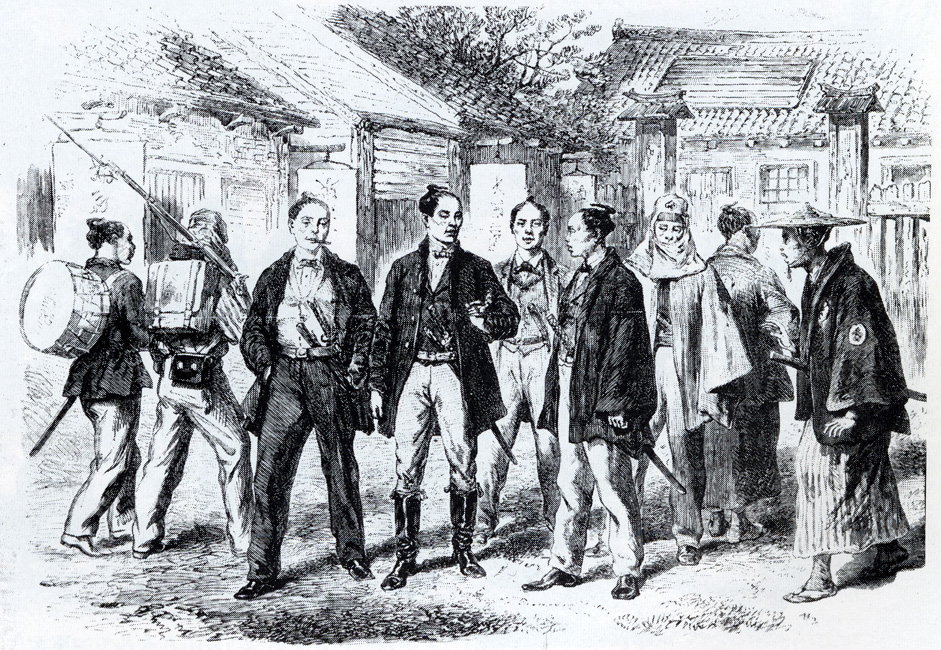

"Samurai in Western Clothing." Illustrated London News, 1866

Once these parties started to work together towards a sense of diplomacy, a positive long-term change became evident. The 1889 Meiji Constitution stood as one of the first diplomatic acts within the Japanese government that did not emerge out of war and violence. Without this type of reform, Japan would have never been linked to events such as World War I and World War II, for they would have never learned the significance of implementing diplomacy within debates. Ultimately, debate with words, rather than arms, brought diplomatic successes for Japan.

Their newfound, peaceful approach to disagreement provided additional opportunities that allowed them to interact better with other countries and transform the perspective of foreigners amongst the Japanese internally. Unfortunately, while the abolition of feudalism in Japan helped the Japanese government achieve diplomatic policies domestically, their imperialistic ambitions hindered them from being able to utilize this approach internationally.