Abolishment of the Edo Feudal Hierarchy:

The Successes and Consequences for Japan

Transfer of Power

"Saigo Takamori with His Officers at the Satsuma Rebellion."

Le Monde Illustré, 1877

With this newfound power, the Meiji government became determined to achieve a centralized government that no longer relied on the structure of feudalism. The imperialists introduced a more straightforward class system in 1869 that made former feudal lords and court nobles kazoku (“peers”)—officials that still maintained significant political power.

Yet, samurai were excluded from this status entirely and were grouped with the remaining citizens as heimin (“commoners”). Consequently, this new classification system no longer provided the standard annual stipends for samurai, causing the samurai class to become impoverished quickly.

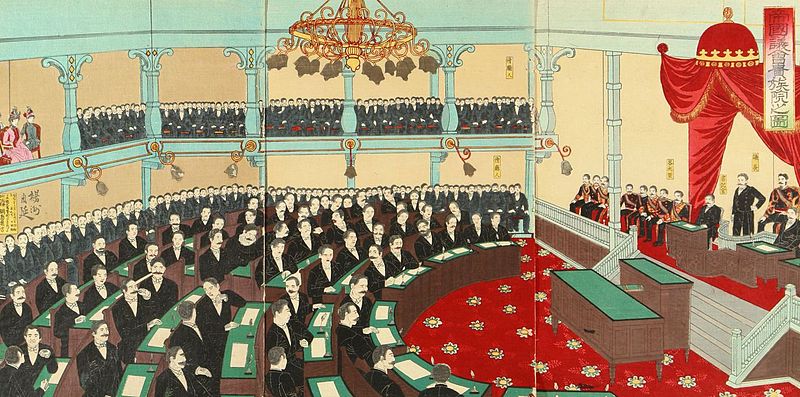

"A Scene in the House of Peers." Chikanobu, Yōshū, 1890

"Conté Portrait of the Emperor Meiji."

Chiossone, Eduardo, 1888.

Many samurai who had supported the imperial throne during the collapse of the Tokugawa now felt conflicted and betrayed. One samurai, Saigō Takamori, proposed to the Meiji administration that the samurai could be of better use in situations like the invasion of Korea. Nonetheless, the imperial court responded to these proposals with threats of completely eradicating the samurai class. Saigo later resigned from the government and would soon lead a significant revolution called the Satsuma Rebellion.

“Portrait of Saigo Takamori."

Nakagawa, C., 1877

"It was a few seconds before I realized his head was cut off... While looking at the bodies, Saigō's head was brought in and placed by his body... It was a remarkable looking head and any one would have said at once that he must have been the leader."

~ John Capen Hubbard, a ship captain who witnessed the Battle of Shrioyama from his ship and visited the scene of the battle afterwards

He and many others fought against the conscript army with reigning support from the samurai class, only for him to meet his demise at the Battle of Shiroyama. His death resonated deeply with the imperial court—so much so that imperialists recognized him as a hero and posthumously pardoned Saigo of his prior crimes.

This became one of the first acts of assent amongst dissenting imperialists and hierarchy apologists that would inadvertently foreshadow their future development to work together to achieve a sense of diplomacy within the Meiji Constitution.