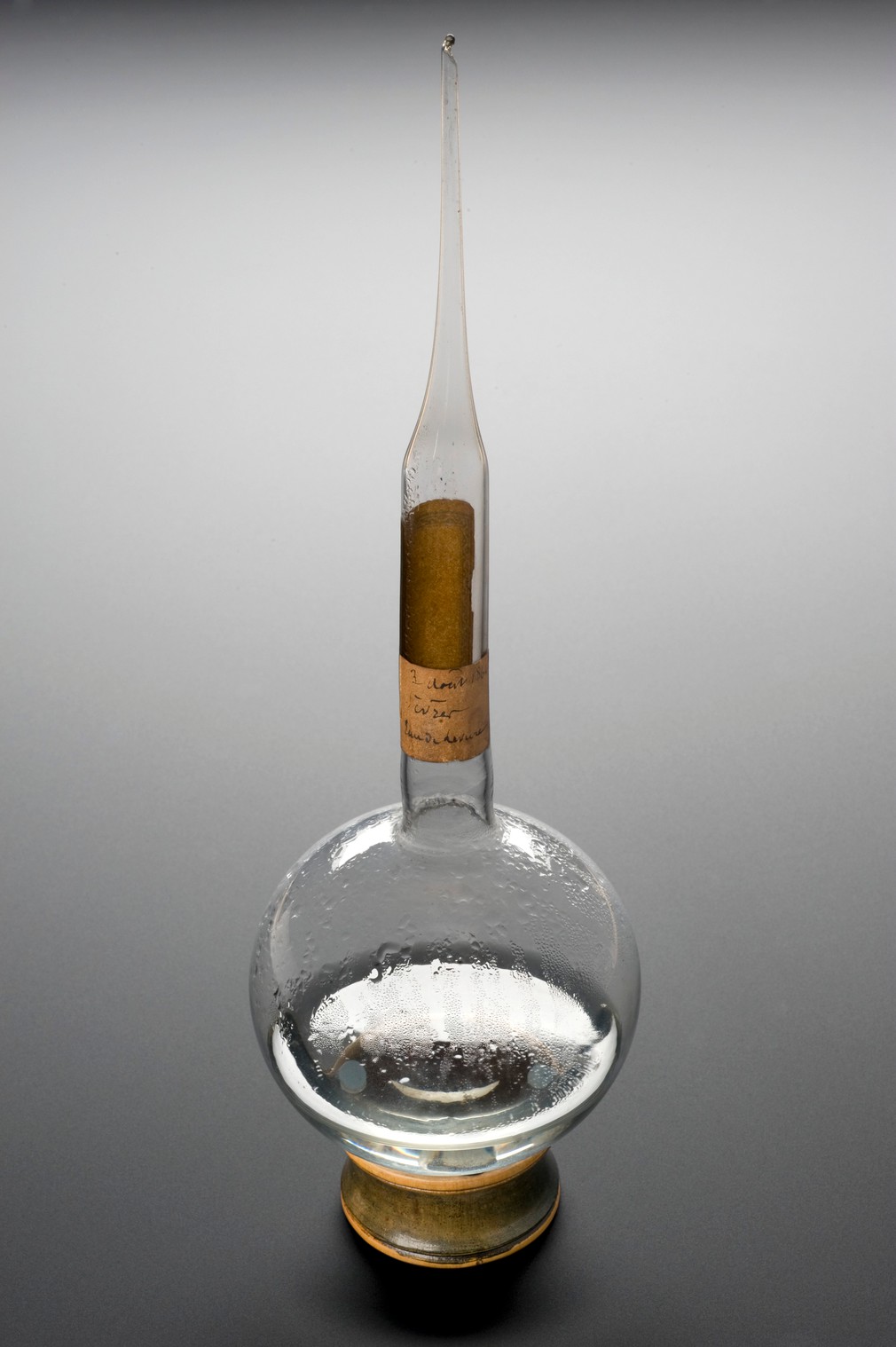

(Flask used in fermentation experiment, Wellcome Collection)

(Common Hall Muscat Grapes, c. 1825, Wellcome Collection)

In 1857, Louis Pasteur studied the fermentation process to prevent France’s wine from spoiling. A popular proposition was that fermentation was a chemical breakdown of the grape juice in the alcohol, but Pasteur disagreed. Pasteur researched the situation and concluded that fermentation was an organic process that was caused by microorganisms. To support this, he replicated fermentation under experimental conditions. This showed that fermentation and yeast multiplication were parallel to each other. He realized that the yeast had to be alive to make alcohol because fermentation was a consequence of multiplying yeast.

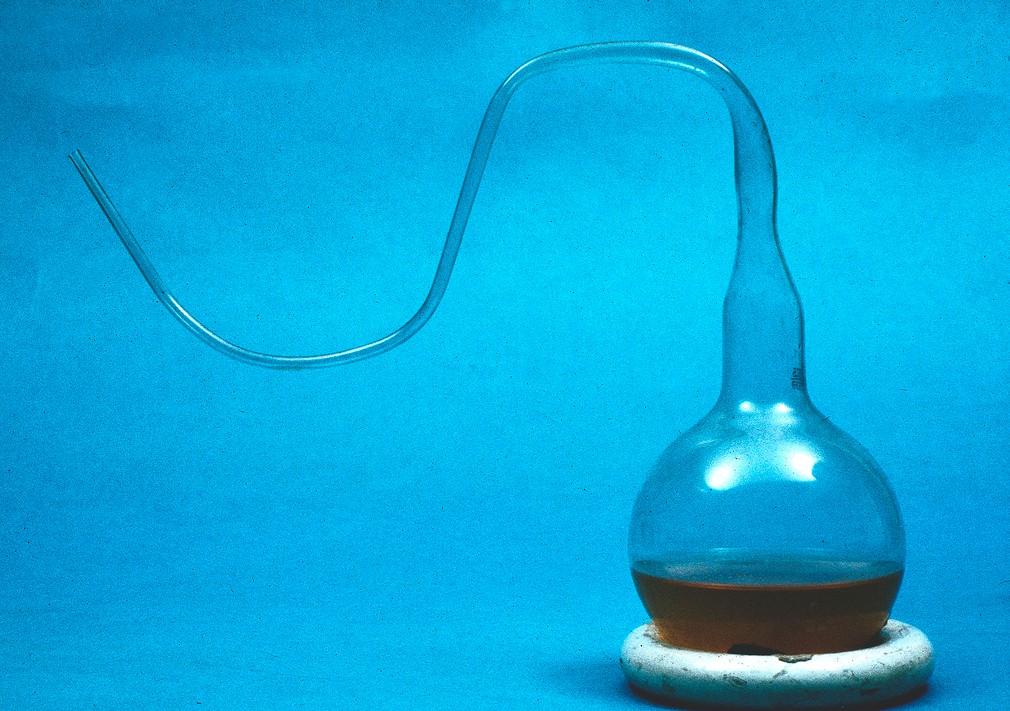

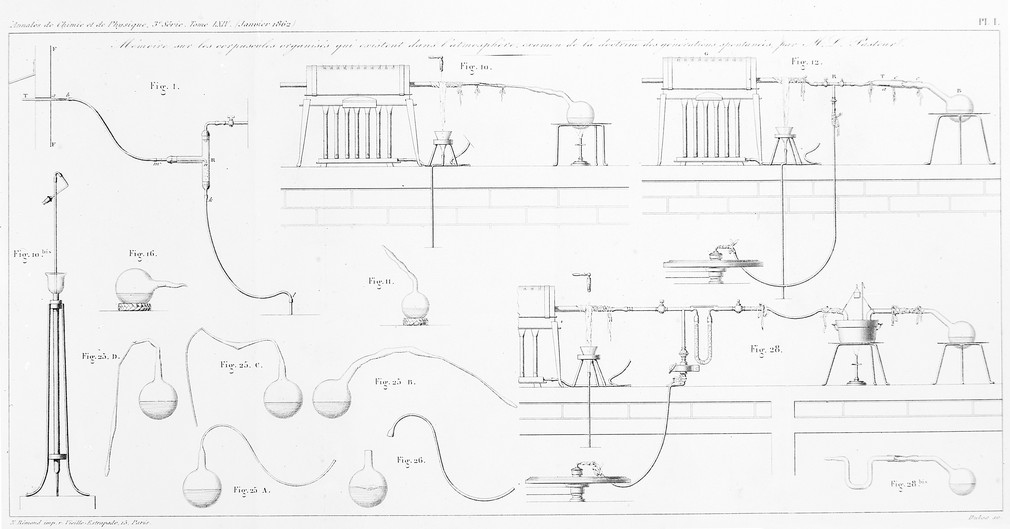

He hypothesized that the broth would remain sterile if the swan neck (see the image on the right) was not broken. In his experiment, he boiled the broth to decontaminate it. Next, he broke some of the flasks' necks so that airborne microorganisms could enter. Its design prevented microbes from getting in while still letting air circulate in the flask. Pasteur was correct because the intact flasks did not grow microbes like the broken ones. In 1865, he patented "pasteurization". He had realized that heating the wine up to a temperature between 60° (140°F) and 100°C (212°F) would remove unwanted microorganisms. This technique was used for other perishable goods.

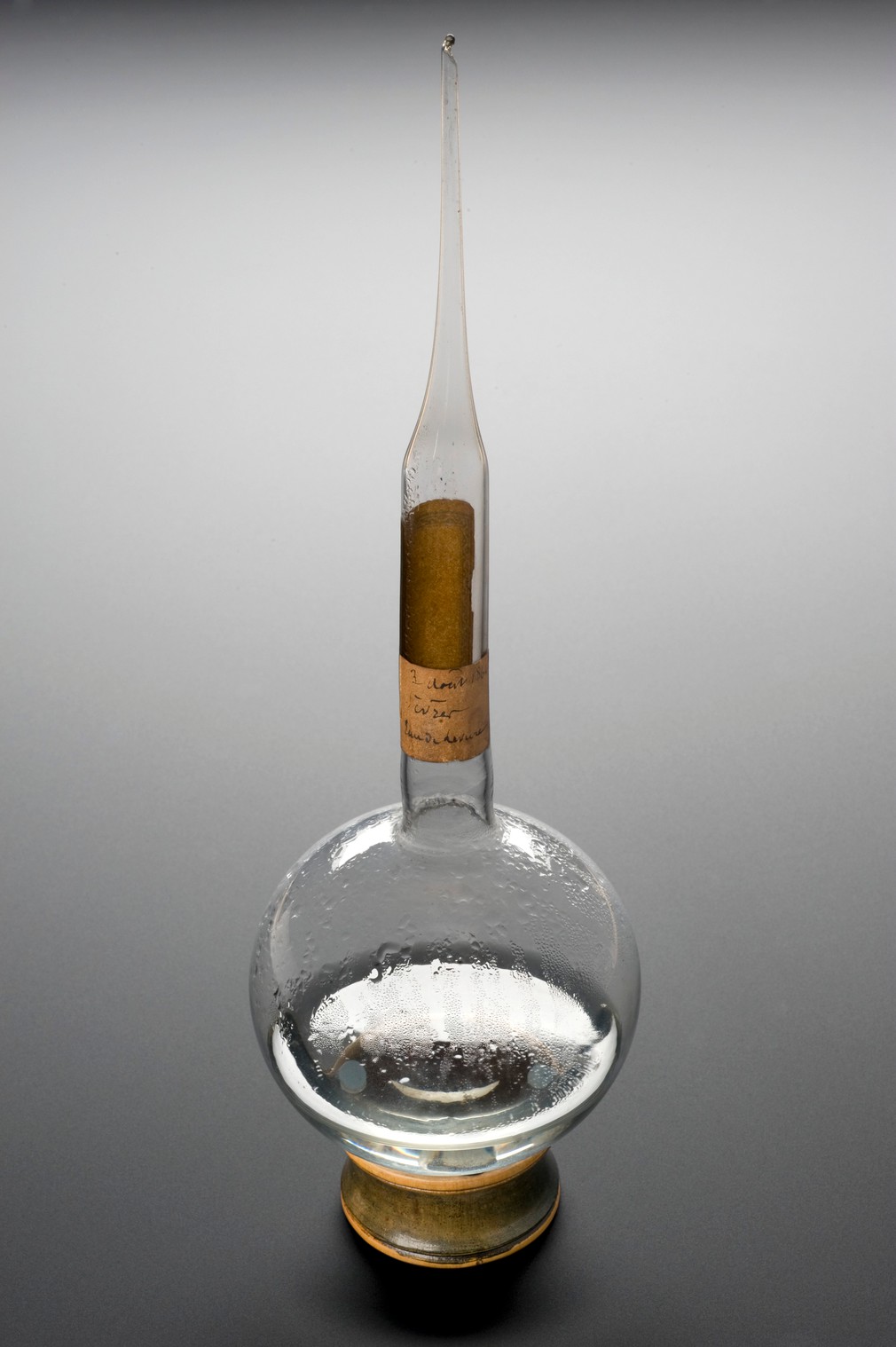

(The control flask, Wellcome Collection)

"...The fermentable liquid was composed of yeast-water sweetened with 5 per cent, of sugar... ferment employed was sacchormyces pastorianus.

The impregnation took place on January 20th. The flasks were placed in an oven at 25 degrees (77 degrees F.)..."

"...FLASK A, WITHOUT AIR.

January 21st.--Fermentation commenced; a little frothy liquid issued from the escape tube and covered the mercury.

The following days, fermentation was active. Examining the yeast mixed with the froth that was expelled into the mercury by the evolution of carbonic acid gas, we find that it was very fine, young, and actively budding.

February 3rd.--Fermentation still continued, showing itself by a number of little bubbles rising from the bottom of the liquid, which had settled bright. The yeast was at the bottom in the form of a deposit.

February 7th.--Fermentation still continued, but very languidly.

February 9th.--A very languid fermentation still went on, discernible in little bubbles rising from the bottom of the flask..."

"...FLASK B, WITH AIR.

January 21st.--A sensible development of yeast.

The following days, fermentation was active, and there was an abundant froth on the surface of the liquid.

February 1st.--All symptoms of fermentation had ceased..."

"...As the fermentation in A would have continued a long time, being so very languid, and as that in B had been finished for several days, we brought to a close our two experiments on February 9th. To do this we poured off the liquids in A and B, collecting the yeasts on tared filters. Filtration was an easy matter, more especially in the case of A. Examining the yeasts under the microscope, immediately after decantation, we found that both of them remained very pure. The yeast in A was in little clusters, the globules of which were collected together, and appeared by their well-defined borders to be ready for an easy revival in contact with air.

As might have been expected, the liquid in flask B did not contain the least trace of sugar; that in the flask A still contained some, as was evident from the non-completion of fermentation..."

~Louis Pasteur's "The Physiological Theory of Fermentation", Translated by F. Faulkner and D.C. Robb

(Flask used in fermentation experiment, Wellcome Collection)

(A glass flask, Wellcome Collection)

(Sketches of Pasteur's equipment, Wellcome Collection)

"...From these facts the following consequences may be deduced:..."

"...1. The fermentable liquid (flask B), which since it had been in contact with air, necessarily held air in solution, although not to the point of saturation, inasmuch as it had been once boiled to free it from all foreign germs, furnished a weight of yeast sensibly greater than that yielded by the liquid which contained no air at all (flask A) or, at least, which could only have contained an exceedingly minute quantity..."

"...2. This same slightly aerated fermentable liquid fermented much more rapidly than the other. In eight or ten days it contained no more sugar; while the other, after twenty days, still contained an appreciable quantity.

...At first, when the air has access to the liquid, much yeast is formed and little sugar disappears, as we shall prove immediately; nevertheless the yeast formed in contact with the air is more active than the other. Fermentation is correlative first to the development of the globules, and... to the continued life of those globules once formed. The more oxygen these last globules have... during their formation, the more vigorous, transparent, and turgescent, and, as a consequence of this last quality, the more active they are in decomposing sugar..."

"...3. In the airless flask the proportion of yeast to sugar was 1/59; it was only 1/79 in the flask which had air at first.

The proportion that the weight of yeast bears to the weight of the sugar is... variable, and this variation depends... upon the presence of air and the possibility of oxygen being absorbed by the yeast. We shall presently show that yeast possesses the power of absorbing that gas and emitting carbonic acid... oxygen may be reckoned amongst the number of food-stuffs that may be assimilated... and that this fixation of oxygen in yeast, as well as the oxidations resulting from it, have the most marked effect on the life of yeast,... multiplication of its cells, and... activity as ferments acting upon sugar, whether immediately or afterwards, apart from supplies of oxygen or air..."

In the experiments... described, fermentation by yeast... as the direct consequence of the processes of nutrition, assimilation and life, when these are carried on without the agency of free oxygen. The heat required... must necessarily have been borrowed from the decomposition of the fermentable matter... from the saccharine substance which... liberates heat in undergoing decomposition. Fermentation by means of yeast appears... to be essentially connected with the property possessed by this minute cellular plant of performing its respiratory functions... with oxygen existing combined in sugar...."

~Louis Pasteur's "The Physiological Theory of Fermentation", Translated by F. Faulkner and D.C. Robb