"Great Migration" (Infobase Learning)

(My Modern Met)

In 1917, the Supreme Court outlawed racial zoning laws, citing the Fourteenth Amendment (Brooks 2011). Although this signaled the end of the government’s public condoning of housing segregation, it failed to relieve housing barriers for Blacks.

“Racial zoning (AKA exclusionary zoning) was a legal way for banks and real-estate agents to keep whites in white neighborhoods and blacks in black neighborhoods.” (Valle 2017)

Prior to World War II, Black Chicagoans faced overcrowding due to the “Great Migration”. The “Great Migration” created a housing shortage that formed the Black Belt, a segregated area of houses in Chicago marked by subpar living standards.

Timuel Black, Civil Rights Activist (The University of Chicago 2014)

"Great Migration" (Infobase Learning)

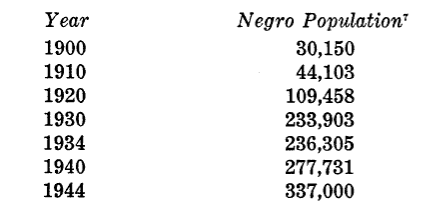

“The year 1915 began the time, known among other things, as that of the "Big Migration." The rapid expansion of industries to meet wartime needs and the shortage of workers created a demand for colored laborers who responded in such great numbers that between 1910 and 1920, sixty-five thousand colored people arrived, making an increase of 150 per cent in the Negro population.” (Sister Claire Marie 1953, 235)

Increase in Black population in Chicago (Sister Claire Marie 1953)

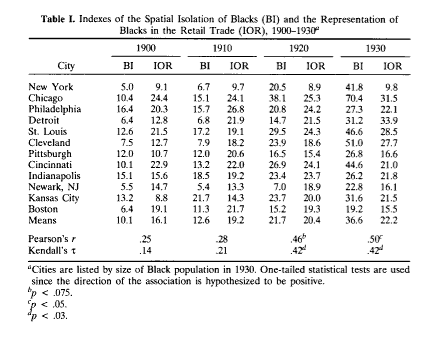

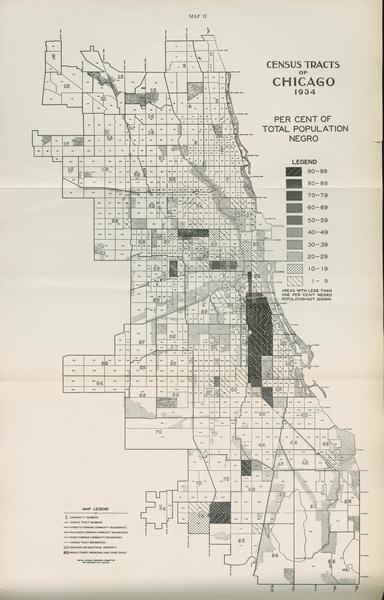

As Black people moved into Chicago, their spatial isolation, or the creation of Black neighborhoods within the city, steadily increased. Specifically, the spatial isolation index (on a scale of 0 to 100) increased from 10.4 to 70.4 from 1910 to 1930.

(Boyd 1998)

By 1930, Chicago had one of the largest urban Black populations, having been a major destination for the Second Great Migration. Failure to alleviate the pre-existing housing crisis led to intensified overcrowding in the Black Belt and worse Black housing opportunities.

“The two decades between 1940 and 1960, and especially the fifteen years following the conclusion of World War II witnessed the renewal of massive black migration to Chicago and the overflowing of black population from established areas of residence grown too small, too old, and too decayed to hold old settlers and newcomers alike.” (Hirsch 1983, 4)

“Chicago and the Great Migration 1915-1950” (The Newberry Library)

“Expansion of the ‘Black Belt’ in Chicago’s South Side” (Infobase Learning)

With racial zoning laws outlawed, private institutions, organizations, and homeowners quickly turned to restrictive covenants to enforce residential segregation to confine Blacks to the Black Belt.

“The forces promoting a durable and unchanging racial border - the dual housing market, the cost of black housing, restrictive covenants - were, at first, buttressed by the housing shortage.” (Hirsch 1983, 29)

“In the mid-1940s, as the housing crisis intensified, the pace of covenant creation and renewal accelerated.” (Hirsch 1983, 56)