Rosewood Reunion

Washington Post

EXPOSING THE UNSPOKEN TRUTH: IDA B. WELLS

Indirect

Fragmented Justice

For more than a century, Southern resistance and Northern indifference has undermined such legislative efforts. Why? Because lynching had remained a powerful terrorist tool to maintain white supremacy. - Louis P. Masur, distinguished professor of American studies and author of "The Civil War: A Concise History"

The fate of the legislation is currently up to the House of Representatives; if the bill does not pass prior to adjournment, the legislation will die and need to begin the process all over again in the 2019 – 2020 session. - NAACP. 2018.

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Law was rejected in 1918 due to Southern protests.

In 2018, the Senate approved the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act: yet to be passed by the House or the President.

“Is it possible for white America to really understand blacks’ distrust of the legal system, their fears of racial profiling and the police, without understanding how cheap a black life was for so long a time in our nation’s history?”

- Philip Dray, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America

Reparations to Black families were only given by some states. The Rosewood bill, for example, provided cash and scholarship to descendants from the Rosewood racial massacre. Though some feel they were assisted, some feel this was done so “they could shut up about it”. Nevertheless, they vow to preserve their history.

Rosewood Reunion

Washington Post

Benea Denson

Washington Post

In Remembrance

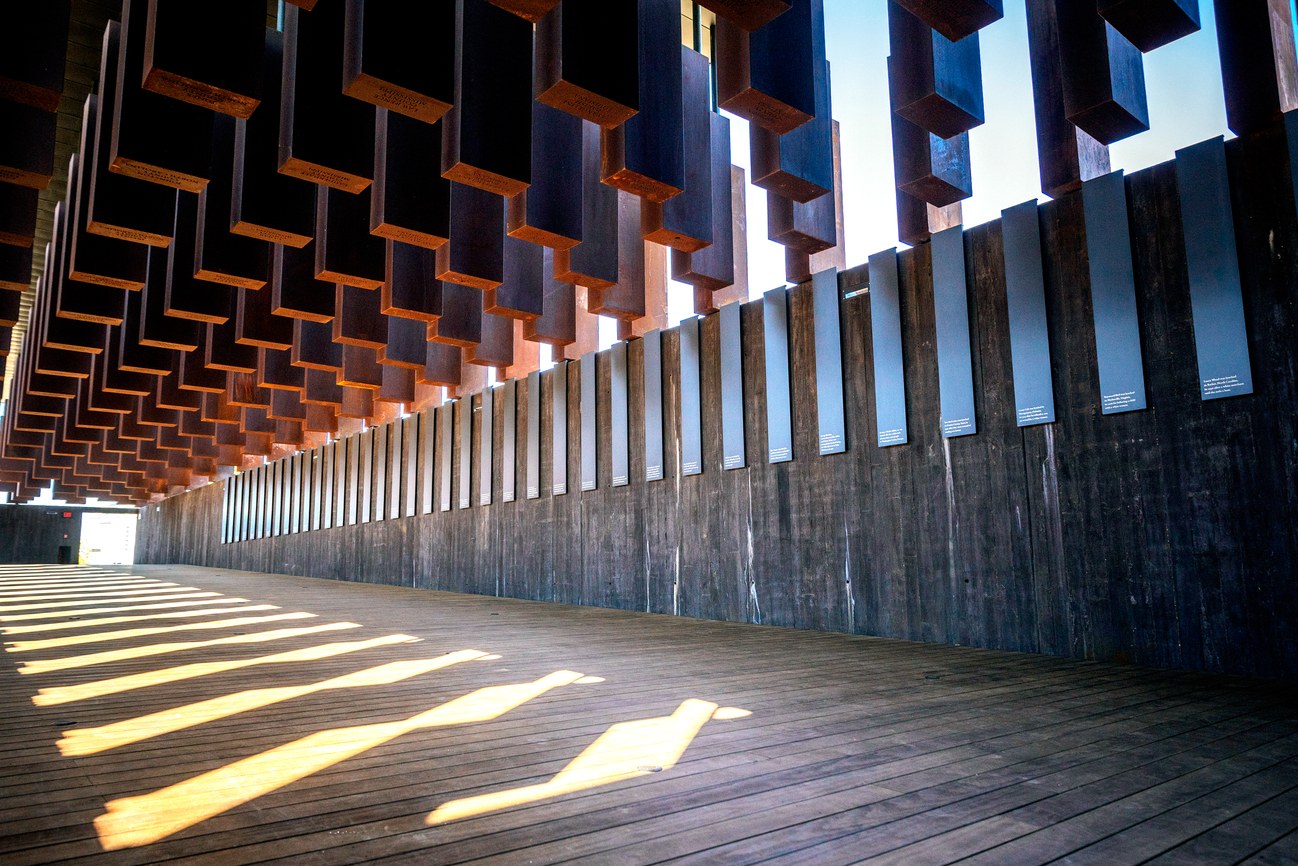

The Equal Justice Initiative is dedicated to aid those denied fair trials. It opened the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opens Thursday on a six-acre site overlooking the Alabama State Capitol, is dedicated to the victims of American white supremacy. And it demands a reckoning with one of the nation’s least recognized atrocities: the lynching of thousands of black people in a decades-long campaign of racist terror. - Equal Justice Initiative

One exhibit wall holds shelves of Mason jars filled with soil from lynching sites. Each jar is labelled with the name of the victim, the date of death, and the county where the lynching took place. - Allyson Hobbs and Nell Freudenberger

Among the first names that a visitor might see are those of the three men on the monument for Shelby County, Tennessee: Calvin McDowell, Thomas Moss, and Henry Stewart. They operated a successful grocery store in Memphis that bested a white business. Their gruesome murders, on March 9, 1892, scarred their friend Ida B. Wells, who spent the rest of her life speaking out and writing the truth about lynching. - Allyson Hobbs and Nell Freudenberger

As founder of EJI and descendent of slaves, Stevenson believes his mission is to bring light to suppressed memories of America's dark history. His memorial represents a continuation of Wells's crusade, and to forgive history, but not forget history.

“I’m not interested in talking about America’s history because I want to punish America. I want to liberate America. And I think it’s important for us to do this as an organization that has created an identity that is as disassociated from punishment as possible.” - Bryan Stevenson, founder of EJI

Steel slabs at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice represents U.S. counties where lynching occurred.(Audra Melton, NYT.)

Enslaved African men and women in a sculpture at the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Jonathan Kelso, NYT.)

A grove on the Memorial site is named in Ida B. Wells's honor. (EJI.)

At the Legacy Museum, jars display soil from lynching sites. Each is labelled with the name of the victim, the date of death, and the county where the lynching took place. (Ricky Carioti, The Washington Post.)

Reconstruction: America After the Civil War

Source: PBS