Healing Through Repatriation: the Debates and Diplomacy Behind the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

The Fight for Repatriation

"Archaeologists say, 'We're trying to find out all this information about your past.' Indians say, 'We don't need you to find out about our past. Our grandmothers told us what we need to know.'"

~ Larry Zimmerman, Professor of Anthropology & Museum Studies and Public Scholar of Native American Representation at Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis

"Bones of Contention." BBC, 1995

During the 1970s and 1980s, as part of the larger civil rights movement, many Native Americans began demanding the return of their ancestors’ remains and objects. However, most museums and archaeologists resisted, claiming that their study of these remains and objects benefited everyone. Native Americans felt that this study violated their beliefs and wanted their sacred items back. The debate between the two sides raged.

"When archaeologist Chris Dill stands among the shelved boxes of bones at the state's Heritage Center, he senses the potential for knowing who the region's earliest inhabitants were, and how they lived and died."

~ Rogers Worthington, Chicago Tribune

"Reburial, with few exceptions, robs the world of important records of environment, life style and human endeavour. It seldom reflects the wishes of the direct descendants. These losses to science, as well as of money which, otherwise, could be used for better health care and education, will seriously affect medical research into cancer, diabetes and arthritis (which affect Native Americans more than any other faction of the general public) as well as cultural studies."

~ E. J. Neiburger, oral pathologist

"We in museums have cared for them and preserved them, and without our efforts they might have been lost."

~ James Van Stone, Field Museum curator

Activists like Maria Pearson fought for the return of remains and objects. Pearson, upon hearing that a young Native American girl’s remains had been uncovered and taken for study, went to the Governor of Iowa’s office to demand that the girl’s remains be returned, and this unfair treatment be halted.

"Maria Pearson." Ames History Museum

"As Indians, we live with that detachment. We do not become attached [to things], or try to own. That’s where we’re different from most non-Indians. They have a drastic need to own Mother Earth, try to own everything."

~ Maria Pearson, Yankton Dakota activist

"You can give me back my people's bones, and you can quit digging them up."

~ Maria Pearson, Yankton Dakota activist

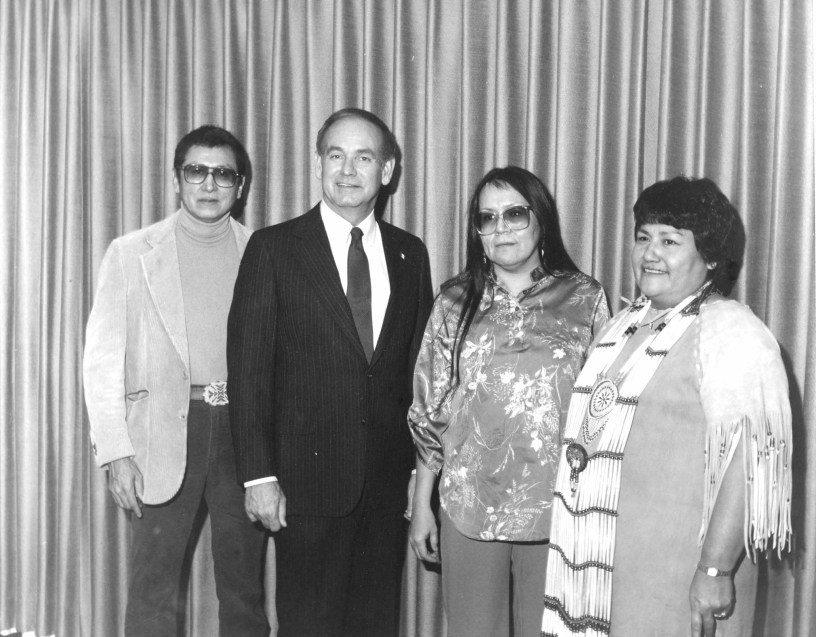

"Iowa Governor Robert Ray is pictured with Maria Pearson,

and her husband, John." Ames History Museum, 1976

"Iowa Governor Robert Ray with Maria Pearson." Center for Art Law / University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist, 1976

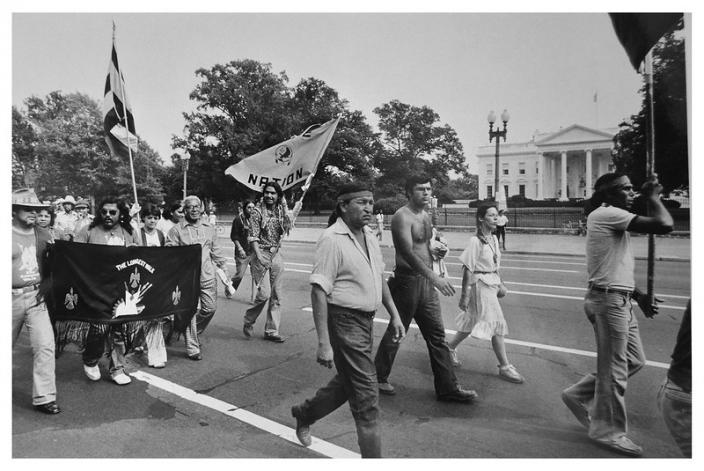

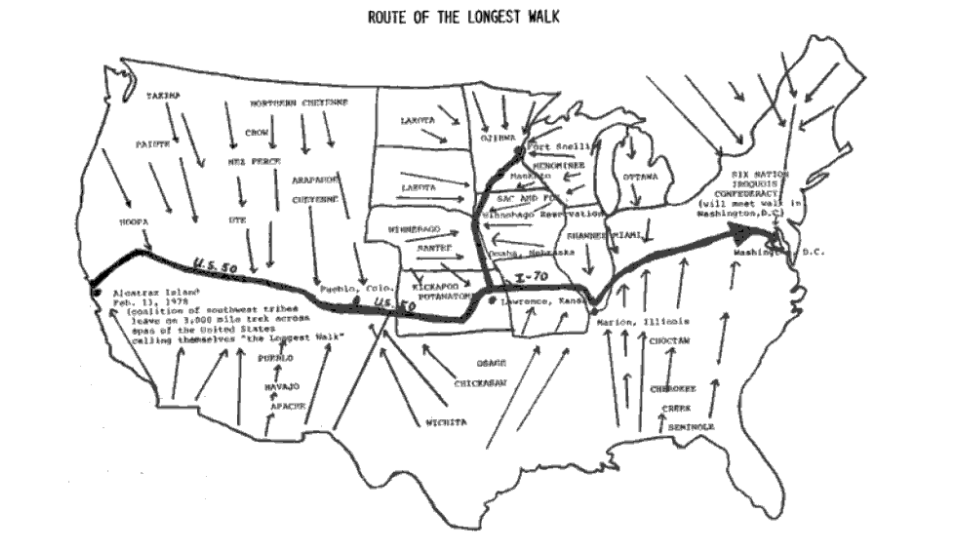

At the same time, peaceful Native American protests occurred. The Longest Walk was a walk across the nation in 1978, which raised awareness of the mistreatment of Native Americans. The walk stopped at many United States museums.

"In 1978, amid a climate of emerging activism among Native American groups, hundreds of Indians began "The Longest Walk" across the country to call attention to Indian issues. In museum after museum along the route the marchers found bones of their ancestors in display cases or in storage, and the disposition of these bones and sacred artifacts became a political and emotional rallying point."

~ Peter Lewis, New York Times

"Native Americans march past the White House." Washington Post / DC Public Library, 1978

"Route of the Longest Walk." Indian Record, 1978