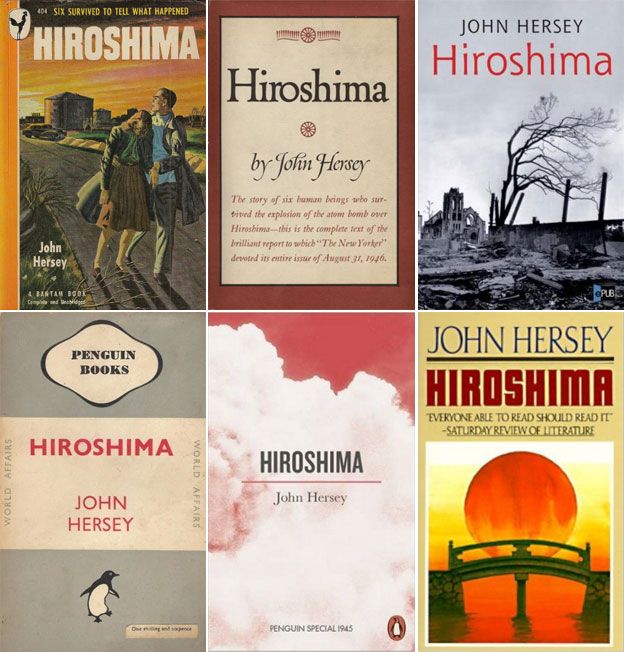

Around the world, people raced to get their hands on the essay. Printed and sold in a variety of languages, there were few places in the world where "Hiroshima" was banned. In Russia, Hersey faced severe backlash from politicians and from the Russian newspaper Pravda, which denounced the bombings and claimed that Hersey was using this as a means to acheive fame.

"Archived communications among John Hersey and his editors, Harold Ross and William Shawn, show that The New Yorker realized that his reporting on Hiroshima and on the true nature of nuclear arms — namely that they were radioactive weapons that continued to kill long after detonation — would be taken by the Soviets as a propagandistic threat."

~ Lesley M. M. Blume and Anastasiya Osipova, "Long After the Bomb, Its Story Finds a New Audience"