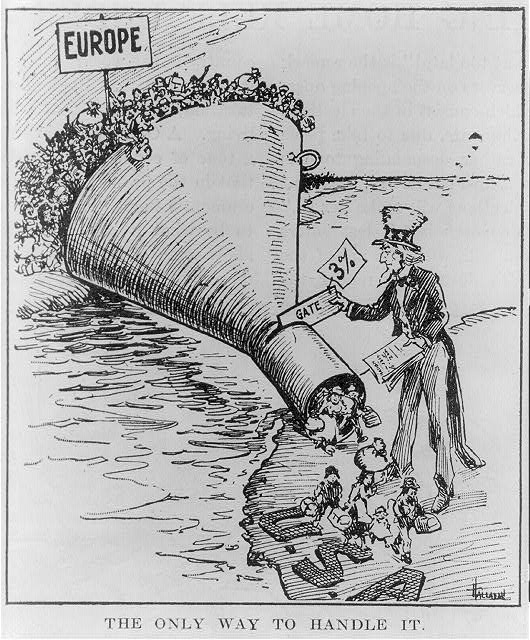

The only way to handle it: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1921

Sugar beets require a prodigious amount of manual labor. About 1/2 - 3/4 of the work is done by hand, so wages greatly affect the overall cost of producing beets (Blakey, 1912). A large, cheap workforce was needed for the expansion of the sugar beet industry.

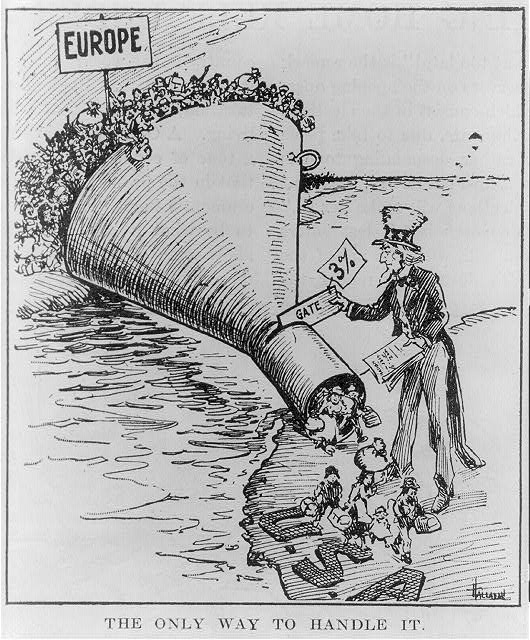

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 set an immigration quota of 2% for each nationality in America, but as it was crafted to target migrants from Europe and Asia, it exempted Mexicans, considering them “non-quota” immigrants (Bloch, 1929). This established a migratory labor framework that allowed the government to ignore workers’ rights, exploit them, and limit their employment mobility.

The only way to handle it: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1921

“...the immigration from Mexico prior to 1911 was relatively unimportant. During the ten years 1901-1910, only six-tenths of one percent of the total immigration into the United States was from Mexico…The rush of immigrants from Mexico began during the World War and was undoubtedly caused by the then prevailing shortage of labor. Although Mexican immigration began during the World War period, the great influx of immigration from Mexico was caused by the passage of the quota laws…during the eleven years preceding the enactment of the 2 percent quota law the number of Mexican immigrants admitted was only 3.8 percent of the total immigration…this percentage increased to 10.9 during the three fiscal years ended June 30, 1924. This shutting off of immigration from European countries undoubtedly gave an added impetus to immigration from Mexico."

Louis Bloch, 1929

Because of Texas's proximity to the Mexican border, the influx of Mexicans concentrated there, but Michigan also needed field laborers. In the early 1920s, Michigan sugar companies sent recruiters south to Texas to hire Mexican seasonal laborers, (Lansing State Journal, 1925; Haack, 2023).

During the season of 1926, 6,720 Mexicans were employed to tend 42,000 acres of sugar beet fields in Michigan. 3,048 Mexicans were shipped by a single company (Edson, 1927).

“‘American boys will not work in the fields with their hands,” said Augustus C. Carton, of the State Department of Agriculture. ‘He will drive the tractor, but when it comes to getting down close to the ground and working with his hands on the plants, as work must be done with sugar beets, he will not do it, as a rule. There are not a sufficient number of them left on the farms and in the rural communities to do this hand labor.'"

Lansing State Journal, 1925

“The [Mexican] peon makes a satisfactory track hand, for the reasons that he is docile, ignorant, and nonclannish to an extent which makes it possible that one or more men shall quit or be discharged and others remain at work; moreover, he is willing to work for a low wage.”

Annual Report of the Commissioner-General of Immigration of 1911, 1911

These comments show the exploitative ideas behind agribusinesses’ want for Mexican labor that kept immigrant laborers stuck doing menial jobs nobody else wanted to do, a scenario that continues today.

R. C. Kedzie, Father of the Sugar Industry in Michigan: Courtesy of the Lansing State Journal

Seasonal workers thinning beets: Courtesy of the Lansing State Journal, 1958

Mexican Child in Migrant Labor Camp: Courtesy of the Dorothea Lange Digital Archive, 1935

“The Mexican signing the contract agrees to block and thin the beet plants, keep the rows hoed and free from weeds, and to pike and top the beets at harvest. Nothing is said in the contract about helping the Mexican, but before the contract is signed a representative of the company is assured that the Mexican can muster sufficient help. This help usually consists of his wife and children…The blocking is done by a grown man, using a wide hoe to strike out the plants to hills from ten to 12 inches apart. The women and children on their hands and knees pull out the weeds and superfluous plants, leaving one vigorous plant in a hill. The hoeing is performed by persons able to handle a hoe. When the beets are harvested the plowing out is done by the farmer, and the adult Mexicans strike off the tops and tails with a topping knife, throwing the beets in piles."

George Edson, 1927

As is displayed in the quote above, beet farming was difficult. Not only that, but it involved child labor.

"Since the war, Mexican workers have been employed in increasing numbers. Each family contracts to take care of so many acres, the area varying with the number in the family group. Both women and children are employed at the work, and the possibility of turning even young children into wage earners is one of the inducements for taking the contract."

Woman and Child Labor, 1923

Moreover, it was not much better than the labor offered from where they had been imported.

“…the workers embarked on this annual trek to the North to take advantage of the better wages and living conditions in the beet farms and to avoid the virulent racial discrimination to which they were subjected in the Southwest, particularly in Texas. However, a close analysis of the daily lives and labor of the beet farm hands shows that the nature of their work, earnings, and standard of living in the North were not too dissimilar from those they encountered in the Lone Star state. Mexican migrant laborers found similar prejudice and social, occupational, and wage discrimination in Texas cotton ranches and in northern sugar beet farms."

Camila Montoya, 2000

Housing for Meixcan sugar beet workers: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1941

Mexican home in sugar beet area: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1941

The average wage a Mexican sugar beet worker was paid in the 1926 season was $143.75 (Edson, 1989). This was shockingly inadequate at best, and their housing was insufficient.

"Tents and huts are provided by the beet sugar companies who employ them. Each family occupies tent, or hut, no matter how large the family or how small the shelter."

Lansing State Journal, 1925

Although these laborers came to Michigan for better opportunities, the jobs lacked fair wages, suitable housing, restrictions on child labor, and were generally discriminatory. The government, despite having regulatory responsibility, chose inaction against abuses of immigrant laborers' rights. These migratory workers were no less deserving of workers' rights than American workers were. They were vital to the success of the industry and should have been protected.