Communicating the Voices of the Unheard:

The Photography of Dorothea Lange

Lange had a new federal assignment during World War II, this time with the War Relocation Authority. After Pearl Harbor, hysterical fears of future Japanese attacks caused President Roosevelt to order the relocation of Japanese-Americans into internment camps in the West. This policy was motivated by longstanding racism against Asian people. German-Americans and Italian-Americans did not face the same level of persecution in America, despite their home countries being Japanese allies.

Lange was personally opposed to this forced relocation, but she understood the value of creating a historical record and felt it was her duty to photograph the injustice.

"It is said, and no doubt with considerable truth, that every Japanese in the United States who can read and write is a member of the Japanese intelligence system."

— FBI report, 1942, quoted in Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment by Linda Gordon and Gary Okihiro

“I remember having to stay at the dirty horse stables at Santa Anita. I remember thinking, ‘Am I a human being? Why are we being treated like this?’ ... This government can never repay all the people who suffered. But, this should not be an excuse for token apologies. I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget.”

— Albert Kurihara, 1981, Santa Anita Assembly Center, Los Angeles & Poston Relocation Center, Arizona (Amerasia Journal)

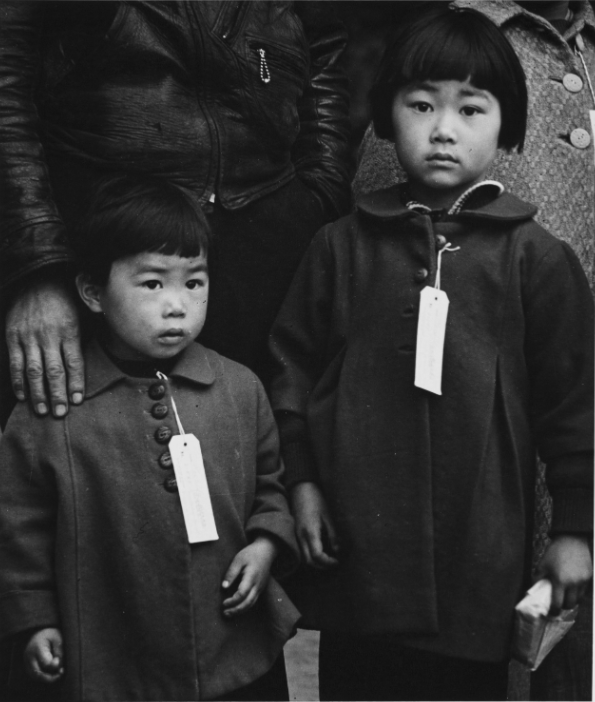

"Two children of the Mochida family who, with their parents, are awaiting evacuation bus," Centerville, CA, May 1942 (The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California)

"Street scene of barrack homes at this War Relocation Authority Center," Manzanar, CA, 1942 (The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California)

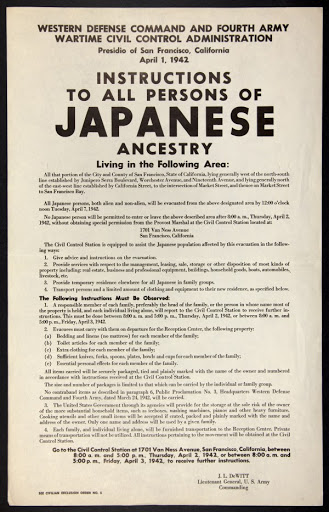

“This War Department Poster, instructing citizens of Japanese descent to report for relocation, has become an iconic symbol of an historic injustice,” 1943 (Oakland Museum of California)

“Lange's earlier work documenting displaced farm families and migrant workers during the Great Depression did not prepare her for the disturbing racial and civil rights issues raised by the Japanese internment. Lange quickly found herself at odds with her employer and her subjects' persecutors, the United States government.”

— "Women Come to the Front," 1995 (Library of Congress)

The WRA imposed strict limits on Lange’s artistic freedom, banning her from speaking to internees and disallowing photographs of barbed wire, armed guards, and the barracks' interiors. Since the government was pushing its own agenda, Lange was severely limited in her ability to communicate the plight of the Japanese-Americans.

"Residents of Japanese ancestry awaiting the bus," Dorothea Lange, April 1942 (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

"Evacuees of Japanese ancestry lining up outside the messhall at noon at this War Relocation Authority center," Dorothea Lange, 1942 (Dorothea Lange Gallery, National Park Service)

"Grandfather and grandson of Japanese ancestry at this War Relocation Authority center," Dorothea Lange, 1942 (Dorothea Lange Gallery, National Park Service)

"Lange photographing Japanese-American evacuees," April 6, 1942 (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

"[The photos] were impounded during the war. Army permission was necessary for their release. They had wanted a record, but not a public record, and [the photos] were not mine."

— Dorothea Lange in a 1968 interview with Suzanne Riess (Bancroft Library, University of California)

Lange's photos of Japanese internment camps never achieved the same publicity as her Depression-era photographs. Instead, the government quietly hid them away. Unlike during the Depression, when the US government attempted to alleviate suffering in America, the government now sought to justify suffering it had intentionally caused. Government officials never intended for the inner workings of the camps to become public knowledge; they merely wanted a clean, private photographic record to protect themselves against accusations of mistreatment. Instead of promoting communication, the government was now actively restricting it.

"Although Ms. Lange’s photographs were commissioned by the federal government as part of its documentary programs, they were suppressed for the duration of the war. Never actively distributed, her prints were sometimes defaced by military personnel, the word “impounded” scrawled across them. After the war ended, the photographs were discreetly deposited in the National Archives, where they remained, largely unseen and unpublished, for decades."

— Maurice Berger in "Rarely Seen Photos of Japanese Internment," 2017 (The New York Times)

"Dorothea Lange: Grab A Hunk of Lightning" (PBS America, 2018)

"The photographs were impounded because they were unmistakably critical. They unequivocally denounced, visually, an unjustified, unnecessary, and racist policy... Sequestering these photographs deprived not only their author but also Americans as a whole... Photography heavily influenced public opinion on these matters, and the Depression and World War II period represented a major leap upwards in that influence."

— Linda Gordon in "Dorothea Lange’s Censored Photographs of the Japanese American Internment," 2017 (The Asia-Pacific Journal)