Communicating the Voices of the Unheard:

The Photography of Dorothea Lange

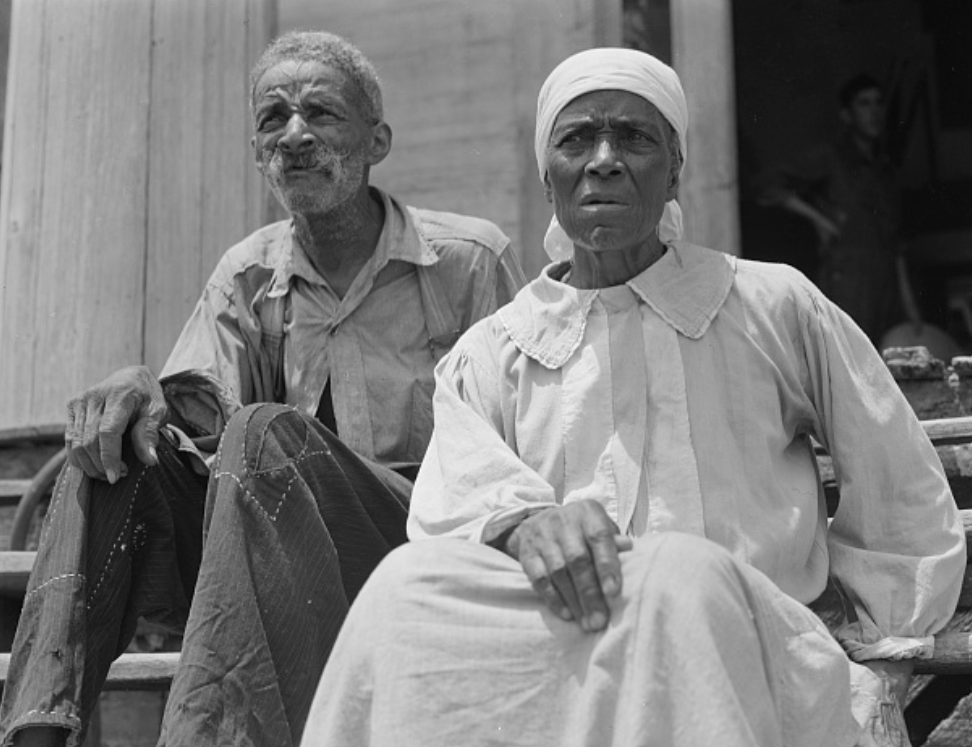

In 1936, Lange’s attention shifted from families who had left their homes to ones who had stayed behind during the Depression, as she and Taylor traveled to the South to study tenancy and sharecropping. There she photographed people who were not often subjects of attention: children, elderly people, ex-slaves, and poor tenant farmers.

While the FSA’s distribution of Lange’s photographs helped the nation see the victims of the Depression, the government mainly worked to distribute pictures of White migrant workers and farmers. Despite this, Lange photographed all minorities alike. Her insistence on capturing all people communicated a complete and accurate record of those impacted by the Depression.

“Take [photographs of] both black and white but place the emphasis on white tenants, since we know that these will receive much wider use."

— Roy Stryker, head of the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration, 1937, quoted in Women in the Arts: Dorothea Lange

"Mexican mother in California. 'Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me, 'We don't want to go, we belong here.''" Dorothea Lange, 1935 (Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration Collection)

"Filipino boy of a labor gang cutting cauliflower near Santa Maria, California" Dorothea Lange, 1937. (Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration Collection)

"This man was born a slave in Greene County, Georgia." Dorothea Lange, 1937 (Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration Collection)

"Ex-slave and wife who live in a decaying plantation house. Greene County, Georgia." Dorothea Lange, 1937 (Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration Collection)

"The government hoped that seeing how much people were suffering would muster a sense of urgency among taxpayers. Because most taxpayers were white, the FSA encouraged Lange to concentrate on white refugees, a suggestion that she actively resisted."

— Jo Lawson-Tancred, in "Hope and Hardship: Dorothea Lange’s America," 2018 (The Economist)

"Lange’s opposition to racism, by contrast, was more than “proto.” It was conscious, considered, and consistent. She made more pictures of people of color — 31 percent of her total output — than did any other FSA photographer."

— Linda Gordon, in "Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist," 2006 (The Journal of American History)

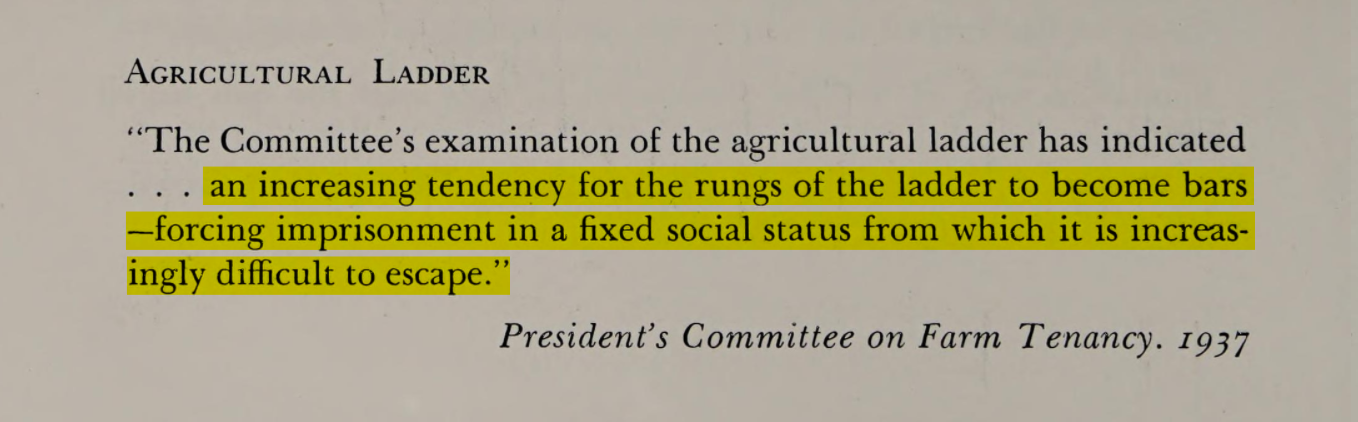

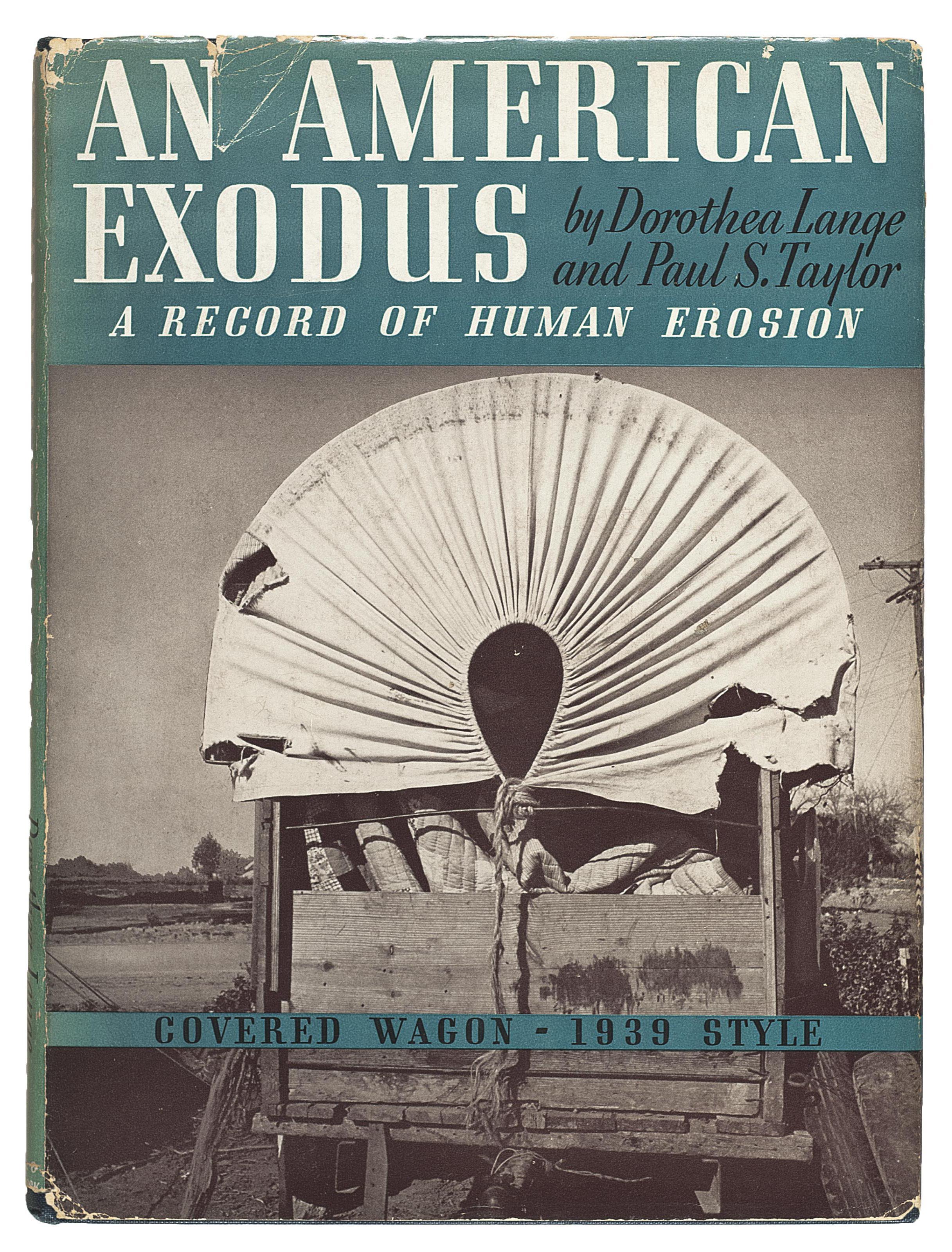

Lange and Paul Taylor publicly documented rural poverty in their 1939 book An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion. They published pictures of minorities and exposed the racism ingrained in the social values of the Deep South and migrant camps in California.

"Our work has produced the book, but in the situations which we describe are living participants who can speak. Many whom we met in the field vaguely regarded conversation with us as an opportunity to tell what they are up against to their government and to their countrymen at large. So far as possible we have let them speak you face to face. Here we pass on what we have seen and learned from many miles of countryside of the shocks which are unsettling them."

— Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor, in the foreword to An American Exodus, 1939

"An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion," page 16, by Dorothea Lange and Paul Schuster Taylor, 1939 (Internet Archive)

"Cover of An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion," Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor, 1939, (The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California)

“Informed by the methods they used while collaborating on government reports, An American Exodus is a compassionate document of the grim economic and environmental circumstances and personal costs of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. Read today, the book appears as a work of love and care for others, but also as a testament to Lange and Taylor’s relationship as partners and lifelong collaborators.”

— River Bullock, in "Written by Dorothea Lange," 2020 (Museum of Modern Art)

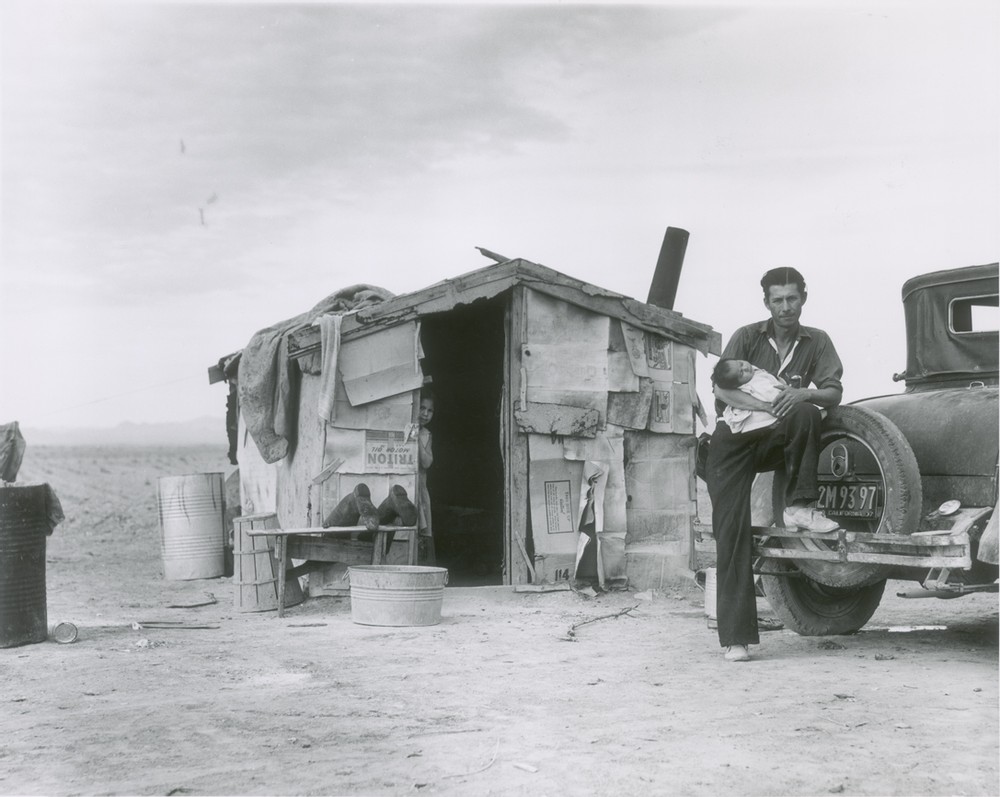

An American Exodus shared diverse photographs of people, showing the true face of rural poverty in America and examining how sharecropping and tenancy often created inescapable suffering for many African American and poor White workers.

“Plantation overseer and his field hands, near Clarksdale, Mississippi” Dorothea Lange, 1936 (The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California)

“Migratory Mexican field worker’s home on the edge of a frozen pea field. Imperial Valley, California” Dorothea Lange. 1937 (The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California)

"Line-up of Negro Unemployed, Memphis" Dorothea Lange, 1938 (Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration Collection)