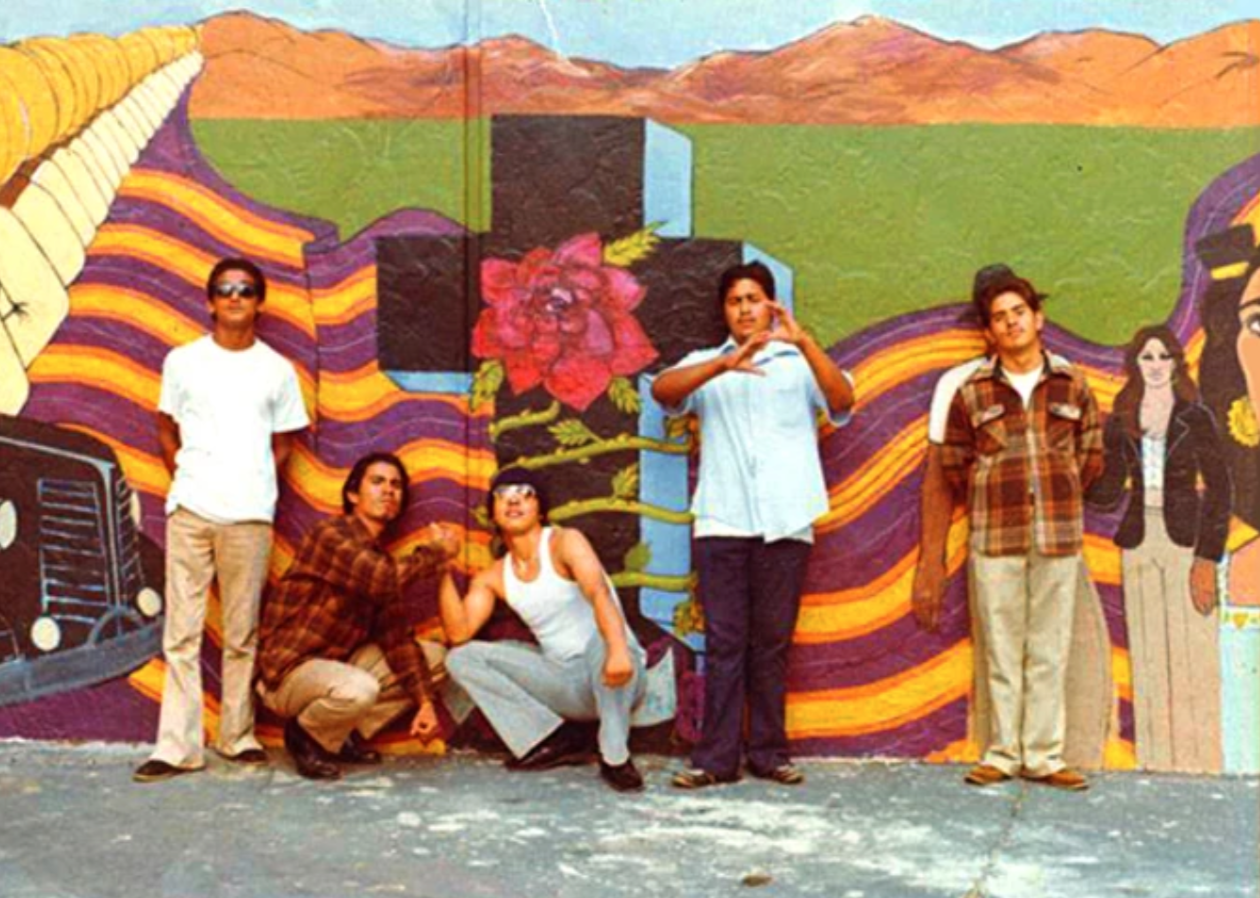

"In 1972, the Chicano art collective ASCO tagged the outside of LACMA, because the museum didn’t show Chicano artists. Two years later, the museum gave another Chicano group, Los Four, a show. But for the museum, it was barbarians at the gate."

- Cheech Marin, Chicano art collector, "Cholo Graffiti.", 2011.

After the Chicano art movement, Chicano artists struggled to gain entrance into museums and be regarded as professional artists.

ASCO. Spray Paint LACMA. 1972. Photo by Harry Gamboa

“It’s always been my contention that Chicanos are a co-equal culture and capable of participating and sharing and contributing. At some level, [the show] just gives people hope that it’s possible to actually create work and have it recognized as being art.”

- Harry Gamboa, member of ASCO artists group who tagged the LACMA