Sadako Sasaki (Manhattan Project National Historical Park)

("Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Ending the Nuclear Threat")

“We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake. We shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.” - President Harry Truman, 1945

“The story is a familiar one, though nonetheless dramatic. In the early morning of 6 August 1945, a American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, lifted off a runway on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Piloted by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, who had named the giant Superfortress after his mother, the Enola Gay carried a ten-thousand-pound atomic bomb known as ‘Little Boy.’ At 8:15 A.M.. the crew of the Enola Gay covered their eyes with dark glasses and the bombardier, Thomas Ferebee, released the huge orange and black bomb over Hiroshima, Japan, a city of 250,000 people, many of whom were starting their last day on earth. The bomb exploded over the city with a brilliant flash of purple light, followed by a deafening blast and a powerful shock wave that heated the air as it expanded. A searing fireball eventually enveloped the area around ground zero, temperatures rose to approximate those on the surface of the sun, and a giant mushroom cloud roiled up from the city like an angry gray ghost. Within seconds Hiroshima was destroyed and half of its population was dead or dying. Three days later, a second atomic bomb destroyed the Japanese city of Nagasaki, killing more than 60,000 people.

The Japanese government surrendered on 10 August 1945, four days after Hiroshima, and day after Nagasaki. The Second World War was over; the atomic age had begun.” (Michael J. Hogan, "Hiroshima in History and Memory", 1996)

“It was, of course, necessary to set the military wheels in motion, as these orders did, but the final decision was in my hands, and was not made until we were returning from Potsdam. Dropping the bombs ended the war, saved lives, and gave the free nations a chance to face the facts.” - President Truman, January 12, 1953

“Hiroshima stands on a flat river delta, with few hills or natural features to limit the blast. The bomb was dropped on the city centre, an area crowded with wooden residential structures and places of business. These factors meant that the death toll and destruction in Hiroshima was particularly high. The firestorm in Hiroshima destroyed 13 square kilometres (five square miles) of the city. Almost 63% of the buildings in Hiroshima were completely destroyed and many more were damaged. In total, 92% of the structures in the city were either destroyed or damaged by blast and fire. Estimates of total deaths in Hiroshima have generally ranged between 100,000 and 180,000, out of a population of 350,000. Tens of thousands died immediately and many more in the days and months that followed.” (“Campaign For Nuclear Disarmament.”)

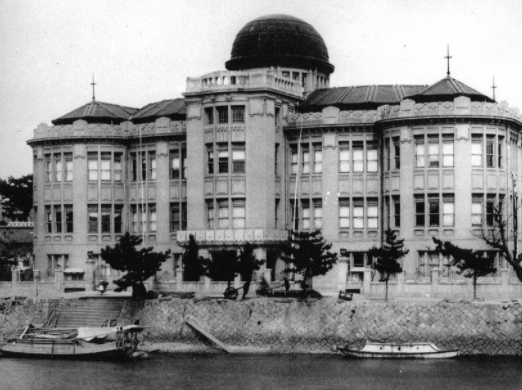

Hiroshima Before The Bombing

Hiroshima After The Bombing

Previously the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, this building is now known as the A-Bomb Dome.

“Due to the hilly geography of Nagasaki and the bombing focus being away from the city centre, the excessive damage from the bombing was limited to the Urakami Valley and part of downtown Nagasaki. The centre of Nagasaki, the harbour, and the historic district were shielded from the blast by the hills around the Urakami River. The nuclear bombing did nevertheless prove devastating, with approximately 22.7% of Nagasaki’s buildings being consumed by flames, but the death toll and destruction was less than in Hiroshima. Estimates of casualties from Nagasaki have generally ranged between 50,000 and 100,000, with many dying instantaneously and others dying slowly and agonisingly as a result of burns and radiation.” (“Campaign For Nuclear Disarmament.”)

These pictures capture Nagasaki both before the atomic bomb was dropped (left), and after (right). The differences between the two were caused by the mass destruction of buildings, clearing the land, and reducing the city to ruins.

A complete analysis of the effects of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left the United States Government Printing Office on June 30, 1946. The document presents the following findings on the effects of radiation exposure in the two cities.

“The seriousness of these radiation effects may be measured by the fact that 95 percent of the traced survivors of the immediate explosion who were within 3,000 feet suffered from radiation disease. Colonel Stafford 'Warren, in his testimony before the Senate Committee on Atomic Energy, estimated that radiation was responsible for 7 to 8 percent of the total deaths in the two cities. Most medical investigators who spent more time in the areas feel that this estimate is 'far too low; it is generally felt that no less than 15 to 20 percent of the deaths were from radiation." (“The United States Strategic Bomb Survey: The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki”, 1946)

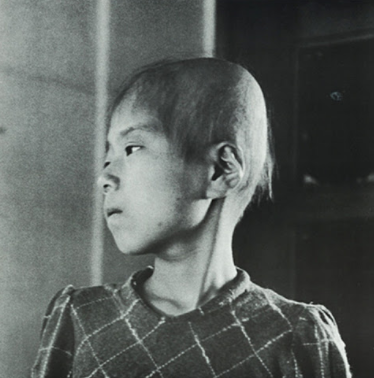

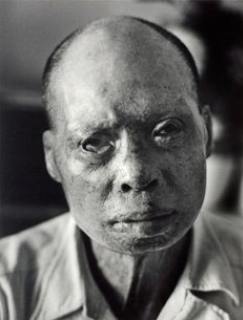

“Autopsies showed remarkable changes in the blood picture-almost complete absence of white blood cells, and deterioration of bone marrow. Mucous membranes of the throat, lungs, stomach, and the intestines showed acute inflammation. . .The majority of the radiation cases, who were at greater distances, did not show severe symptoms until 1 to 4 weeks after the explosion, though many felt weak and listless on the following day. After a day or two of mild nausea and vomiting, the appetite improved and the person felt quite well until symptoms reappeared at a later date. The first signs of recurrence were loss of appetite, lassitude, and general discomfort. Inflammation of the gums, mouth, and pharynx appeared next. Within 12 to 48 hours, fever became evident. . .The other symptoms commonly seen were shortage of white corpuscles, loss of hair, inflammation and gangrene of the gums, inflammation of the mouth and pharynx, ulceration of the lower gastro-i~testinal tract, small livid spots (petechiae) resulting from escape of blood into the tissues of the skin or mucous membrane. . .The white blood count in the more severe cases ranged from 1,500 to 0, with almost the entire disappearance of the bone marrow." (“The United States Strategic Bomb Survey: The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki”, 1946)

Survivors of Hiroshima suffered from radiation (first two pictures), as well as injuries from heat and debris (last two pictures).

"Sterility has been a common finding throughout Japan, especially under the conditions of the last 2 years, but there are signs of an increase in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki areas to be attributed to the radiation. Sperm counts done in Hiroshima under American supervision revealed low sperm counts or complete aspermia for as long as 3 months afterward in males who were within 5,000 feet of the center of the explosion. The effects of the bomb on pregnant women are marked, however. Of women in various stages of pregnancy who were within 3,000 feet of ground zero, all known cases have had miscarriages. Even up to 6,500 feet they have had miscarriages or premature infants who died shortly after birth. . . Two months after the explosion, the city's total incidence of miscarriage, abortion, and premature births was 27 percent as compared with a normal rate of 6 percent." (“The United States Strategic Bomb Survey: The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki”, 1946)

"There is reason to believe that if the effects of blast and fire had been entirely absent from the bombing, the number of deaths among people within a radius of one-half mile from ground zero would have been almost as great as the actual figures and the deaths among those within 1 mile would have been only slightly less. The principal difference would have been in the time of the deaths. Instead of being killed outright as were most of these victims, they would have survived for a few days or even 3 or 4 weeks, only to die eventually of radiation disease." (“The United States Strategic Bomb Survey: The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki”, 1946)

The United States Strategic Bomb Survey concluded that, had there been no physical impact associated with the atomic bombs, radiation alone would result in fatalities of the same magnitude. The only difference being that the deaths would occur up to several weeks later, instead of instantaneously.

"Leukaemia was the first cancer to be associated with atomic bomb radiation exposure, with preliminary indications of an excess among the survivors within the first five years after the bombings. An excess of solid cancers became apparent approximately ten years after radiation exposure. With increasing follow-up, excess risks of most cancer types have been observed, the major exceptions being chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, and pancreatic, prostate and uterine cancer. . .There are also excess risks of various types of non-malignant disease in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors, in particular cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive diseases." ("Cancer and non-cancer effects in Japanese atomic bomb survivors")

Sadako Sasaki (Manhattan Project National Historical Park)

"Sadako Sasaki was two years old on August 6th, 1945 when pilot Paul Tibbett of the United States Air Force flew his B-29 bomber airplane over the city of Hiroshima, Japan. . . Sadako and family lived a little over one mile from the bomb’s hypocenter. A blinding white light flashed through the city, and a huge boom was heard miles away when Little Boy exploded over Sadako’s hometown. . . By all appearances, Sadako was a happy and healthy child. She was known to be a fast runner and popular with her classmates. That is why it came as such a surprise when at the age of twelve, Sadako began to show symptoms of leukemia, and had to be admitted into the hospital. While in the hospital, Sadako remained optimistic and resilient. . . Japanese folklore says that a crane can live for a thousand years, and a person who folds an origami crane for each year of a crane’s life will have their wish granted. The story of the origami cranes inspired Sadako. . . Sadako soon filled her room with hundreds of colorful origami cranes of all different sizes. After folding her thousandth crane, Sadako made her wish, to be well again. Sadly, Sadako’s wish did not come true. Surrounded by family, with 1,300 origami cranes in her room and hanging overhead, Sadako passed away at the age of twelve.” (Manhattan Project National Historical Park, “The Story of Sadako Sasaki”)

Sadako Sasaki was just one of hundreds of thousands of people, who were impacted by the dropping of the atomic bomb. Her story is one that emphasizes how innocent people were negatively impacted by miscommunication on a global scale.

The introduction and use of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the world into an atomic age. Weapons and technology were being modified to bring such bombs as these into existence, and slowly, more nations beyond the United States were in possession of atomic weapons.

"Thirty-five years later both the United States and the Soviet Union had thousands of atomic weapons. The first bombs were like the pyramids of Egypt and the Great Wall of China: visible, dramatic, singular public works projects, the fruit of an enormous, centrally directed concentration of resources. Three years and $2 billion had been required to make them. Now the explosives, if not the vehicles for delivering them, are more like automobiles: mass-produced, with periodic minor improvements. Even as the first two bombs were vastly more powerful-than all previous man-made explosives, so the present models are far more devastating than those that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. . . Their successors are based on the fusing of atoms together. The explosive force of fusion, or hydrogen bombs is measured in the millions of tons of TNT equivalent." ~ Professor Michael Mandelbaum, "The Nuclear Revolution: International Politics Before And After Hiroshima", 1981

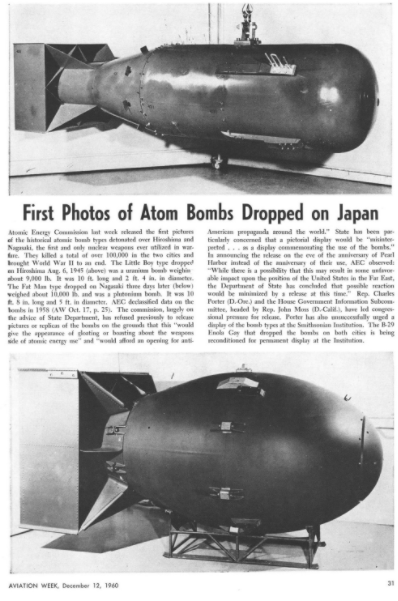

The atomic bombs "Little Boy" (top left) and "Fat Man" (bottom left) were made in August, 1945. The Soviet hydrogen bomb (right) was made ten years later in 1955.

"How have nuclear weapons affected international politics? They have not produced a revolutionary change in the international system. Relations among sovereign states are still governed by the principle of anarchy. War is still possible. . . Still, it is plain that nuclear weapons have had something to do with the peace that has prevailed at the heart of the international system since the end of World War II. National leaders have said that they exert a restraining influence. In crises, when the United States and the Soviet Union have seemed on the verge of war, the record shows that their fear of nuclear devastation has influenced the calculations that have been made." ~ Professor Michael Mandelbaum, "The Nuclear Revolution: International Politics Before And After Hiroshima", 1981

While the existence of nuclear weapons causes great concern for national leaders, it has not resulted in the possibility of war between nations to increase. In fact, it has yielded the opposite results, as leaders are more fearful of nuclear warfare than they were of a war without it. This causes them to be more cautious when handling foreign affairs, and facilitates their willingness to seek peace over conflict. Even without the direct threat of the use of nuclear weaponry, the subconscious knowledge of their existence, guides leading politicians to be more deliberate with their actions.

The destruction of two cities, hundreds of thousands of lives lost, devastating side effects to radiation, and a looming threat of mass destruction held over the heads of leaders worldwide. Much of this, if not all, could have been prevented or postponed, had efficient communication been held between the United States of America and Japan. But, because of the tragic misuse of the word "mokusatsu", thousands of people suffered immediately as a result of the bombing, and the sudden reveal of nuclear weapons altered the way wars would be held for years to come.