Japanese Prime Minister, Kantaro Suzuki ("Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures")

("Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Ending the Nuclear Threat")

English Translation of a quote said during the Prime Minister’s press conference (excluding the phrase “mokusatsu suru” for ease of identification):

“The government of Japan does not consider it [The Potsdam Declaration] having any crucial value. We simply mokusatsu suru."

- Suzuki Kantarō, Prime Minister of Japan, 1945

"According to the commonly accepted story, Japan chose to spurn the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, which called upon her to surrender, and thereby brought down upon her head the atomic bombing and the Russian declaration of war against her. A close examination of the Japanese response to the Potsdam Declaration will show, however, that the Japanese government never intended to reject the Potsdam Declaration. It’s policy was that of mokusatsu, which was quite a different thing from rejection."

~ Kazuo Kawai, “Mokusatsu, Japan’s response to the Potsdam Declaration”, November, 1950

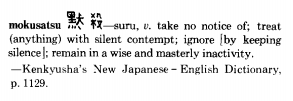

Dictionary Definition of "Mokusatsu," located above the essay titled, "Mokusatsu: One Word, Two Lessons"

“At first look, the Japanese word mokusatsu seems to be pretty simple. The word is a combination of two kanji: the moku- (黙) is found in words like 黙る meaning ‘to be silent’; combined with -satsu 殺, the kanji found in words like 殺人 (A killer). In short, it means to kill something by ignoring or remaining silent about it.” (Matthew Coslett, “The Japanese Art of Silence,” 2014)

"Reporters in Tokyo questioned Japanese Premier Kantaro Suzuki about his government's reaction to the Potsdam Declaration. Since no formal decision had been reached at the time, Suzuki, falling back on the politician's old standby answer to reporters, replied that he was withholding comment. He used the Japanese word mokusatsu, derived from the word for ‘silence.’ As can be seen from the dictionary entry quoted at the beginning of this essay [located above], however, the word has other meanings quite different from that intended by Suzuki. Alas, international news agencies saw fit to tell the world that in the eyes of the Japanese government the ultimatum was ‘not worthy of comment." ("Mokusatsu: One Word, Two Lessons", 2013)

Japanese Prime Minister, Kantaro Suzuki ("Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures")

The miscommunication that took place as a result of Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki’s use of the word “mokusatsu” reiterates the idea that, while the receiver of information is burdened with the task of correctly understanding what is being communicated to them, the sender of information is equally responsible for making their intended message clear. Ambiguity surrounding the word allowed for Suzuki's message to be interpreted in a variety of ways.

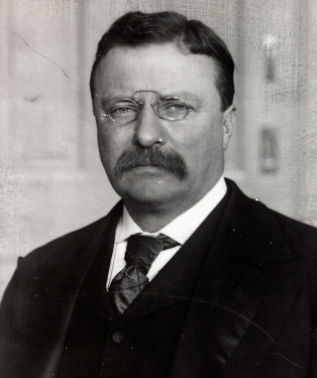

"The fault for the mokusatsu incident is not entirely the translator's. Believe it or not, the real culprit is no less a personage than Kantaro Suzuki, the Japanese Prime Minister himself! After all, there would have been no translation problem if he had not used an ambiguous word for such an important statement. However, politicians are notorious for preferring words that are either meaningless or so full of meanings that no one can be sure of just what they do mean. In all probability the word mokusatsu was well beloved by Japanese officials as their equivalent of ‘No comment!’ simply because it does have such a broad spectrum of meanings. A politician could use it and not really be saying anything he couldn't squirm out of later; but it also left him the opportunity to claim later that he had long been against the course of action under discussion. Terms like these are the ones that Theodore Roosevelt once referred to as ‘weasel words'." ("Mokusatsu: One Word, Two Lessons", 2013)

“One of our defects as a nation is a tendency to use what have been called weasel words. When a weasel sucks eggs it sucks the meat out of the egg and leaves it an empty shell. If you use a weasel word after another there is nothing left of the other.”

- Theodore Roosevelt, May 31, 1916

Theodore Roosevelt (Britannica)

“It is the multiple possibilities offered by silence that make mokusatsu such a useful term for politicians and protestors. For this reason, either the word or the action are commonly used as answers to difficult questions. After all, why risk incriminating yourself or saying something foolish when everyone interprets silence in their own way?

For him [Prime Minister Suzuki], the reply of ‘mokusatsu’ was an attempt to keep everyone happy. The militarists who were a huge problem at the time could take the harshest meaning and imagine a strong Prime Minister contemptibly brushing aside the foreign bully boys; while the more peace-loving politicians could assume that the statement indicated that surrender wasn’t off the table. Unfortunately, the Allies hadn’t asked for a cleverly-considered, ambiguous answer that tried to appease everyone, they wanted ‘the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces’.” (Matthew Coslett, “The Japanese Art of Silence,” 2014)

Japan's response to the Potsdam Declaration suffered a variety of impediments that ultimately transformed it into a fatal miscommunication. Kantaro Suzuki's use of vague language to develop an unclear message; the conscious decision, made by reporters and news agencies, to interpret Suzuki's response as a display of disdain for the authors of the Potsdam Declaration; and a tendency of politicians to ensure they always have a way out, all contributed to a breakdown in communication between the United States and Japan.

"Some years ago I recall hearing a statement known as ‘Murphy's Law’ which says that ‘If it can be misunderstood, it will be.’ Mokusatsu supplies adequate proof of that statement. After all, if Kantaro Suzuki had said something specific like ‘I will have a statement after the cabinet meeting,’ or ‘We have not reached any decision yet,’ he could have avoided the problem of how to translate the ambiguous word mokusatsu and the two horrible consequences of its inauspicious translation: the atomic bombs and this essay." ("Mokusatsu: One Word, Two Lessons", 2013)