Historical Context

Before Internment

In the years prior to WWII, the Japanese immigrated to America in hopes of new opportunities and a new start. However, the reality was that Japanese-Americans had few rights and faced unfair treatment.

“…Japanese Americans on the West Coast had long been special targets of white hostility. Laws and customs shut out Japanese Americans from full participation in economic and civic life for decades. Japanese immigrants – known as Issei – could not own land, eat in white restaurants, or become naturalized citizens” (Densho).

Japanese Americans faced discrimination from federal laws. In 1913, California passed the “alien land law” and prevented aliens who are ineligible for citizenship from buying farmland. Soon, many other states began to create similar laws. Early Japanese immigrants often resorted to traditions back in Japan such as farming. The people farmed for a living and this being restricted left them unable to provide for themselves.

Events Leading to Internment

As the war spread in Europe, the U.S. remained neutral, but this would change as U.S. naval base Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Axis-allied Japan. This attack frightened the nation and led to President Roosevelt enacting Executive Order 9066.

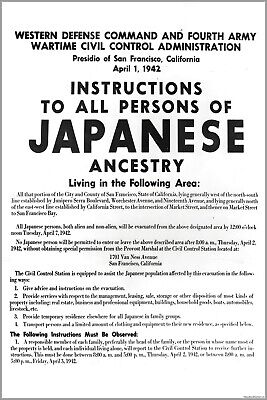

“On February 19, 1942, just over two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066… it had a specific target: the more than 110,000 Japanese Americans living along the West Coast, whom the order would soon force into internment camps” (PBS).

There was no clear evidence that Japanese Americans aided the Axis Powers, yet under the fear of another attack, the decision was made. Executive Order 9066 allowed for the forceful removal of anyone deemed a threat, resulting in the countrywide relocation of Japanese Americans. The order remained in effect until Executive Order 9742 was enacted in 1946, allowing Japanese-Americans to return home.

“Exclusion Order posted at First and Front Streets directing removal of Japanese people”, 1945, Wikipedia.