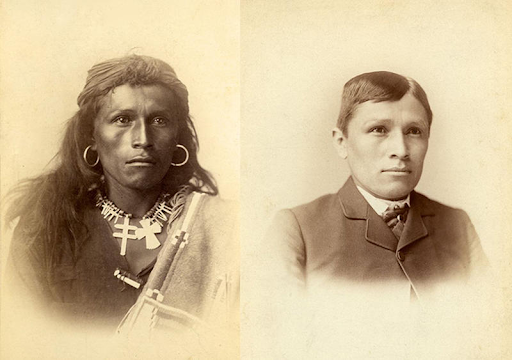

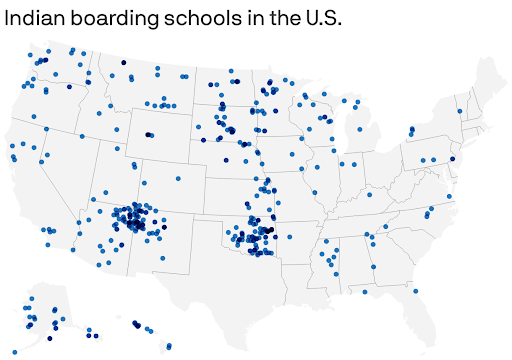

"Between 1900 and 1920 the case against off-reservation school was made along four lines: the belief that Indians, either because of inborn racial traits or sheer obstinacy, were incapable of rapid assimilation; the belief that boarding schools, however effective, were unjustifiably cruel to both parents and children; the belief that such institutions encouraged long-term governmental dependency; and finally, the belief that Native American life ways, rather than being condemned as universally worthless and thereby deserving of extinction, might serve instead as a fruitful foundation for educational growth."

--David Wallace Adams

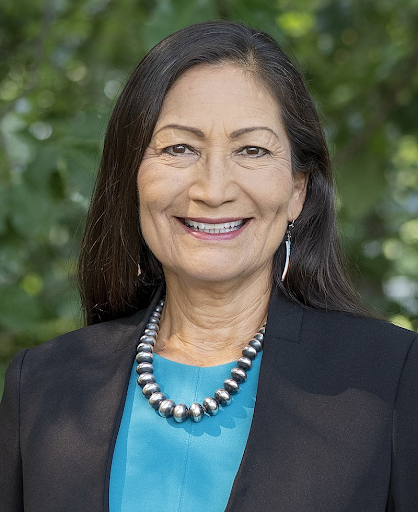

“The consequences of federal indian boarding school policies—including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old—are heartbreaking and undeniable.”

--Interior Department Secretary Deb Haaland