Hodges, Andrew. "Alan Turing: The Enigma." Turing.org.uk, www.turing.org.uk/

scrapbook/ww2.html. Accessed 6 Apr. 2020

"If the possible different Enigma keys were tested at the rate of one per second, it would take five million million years to try them all. So how could Alan Turing's ingeniously designed bombe make any impact, however fast it ran?" - Derek Taunt

Smith, Michael, and Ralph Erksine, editors. Action this Day : Bletchley Park : From the

Breaking of Enigma to the Birth of the Modern Computer. London, Bantam, 2002.

"Enigma" ["Enigma"]. Enigma.umww.pl, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic

of Poland, 2017, enigma.umww.pl/en/. Accessed 6 Apr. 2020

"Tackling Enigma (Turing's Enigma Problem Part 2) - Computerphile." Youtube.com, YouTube, 9 Dec. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=kj_7Jc1mS9k. Accessed 6 Apr. 2020.

Turing took on solving the unbreakable naval Enigma. Though facing 150,738,274,937,250 odds, he wasn't in the dark.

"A single contradiction is enough to eliminate all the billions of possible plugboards, on this hypothetical machine. Sheer numerical size, therefore, may be insignificant, compared with the logical properties of the cipher system."

"But these contradictions would make something go very wrong for Germany and lead to

bridges falling down."

Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing - the Enigma. Princeton, New Jersey, Oxford : Princeton UP, 2014.

“[Turing] recognized that the Polish machine helped to identify keys by asking, in mathematical terms, whether the enciphered message keys of the cryptogram were consistent with the unknown basic setting that was wanted. The bombe actually did this by recontradictory situations to be tested to see whether their settings yielded German when applied to the intercepts."

Kahn, David. Seizing the Enigma : The Race to Break the German U-Boat Codes, 1939-1943. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Mans, James. Alan Turing's Office

in Hut 8, Bletchley Park.

"The concept of the bombe owed several ideas to the Poles ... But the fundamental mathematical insight behind the British bombe was wholly Turing's."

Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits : The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York, Touchstone Book, 2002.

Turing deduced:

"the behaviour of the computer at any moment is determined by the symbols which

he is observing."

Copeland, Jack B. The Essential Turing. PDF ed., Oxford, Oxford UP, 2004.

Hodges, Andrew. "Alan Turing: The Enigma." Turing.org.uk, www.turing.org.uk/

scrapbook/ww2.html. Accessed 6 Apr. 2020

Turing understood the bomba’s analytical computation. He applied his own mathematical theories and designed his own machine - one playing an imitation game in codebreaking.

March 1940, Turing achieved a feat exceeding Rejewski's. Laying out the Enigma’s whole theoretical structure in its variations, Turing's bombe was built - the machine that would save lives and vast work-hours.

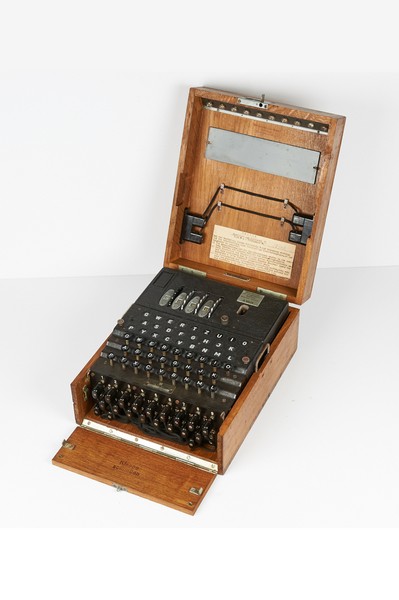

The bombe was

"something of a scientific miracle that in time much transcended Enigma itself. It was at first an electromechanical ... aimed to adjust itself to whatever alterations the Germans might make in the arrangement of the three rotors and ten pairs of plugs of the Enigma mechanism."

- Harold Deutsch

Bateman, Gary M. "THE ENIGMA CIPHER Machine." American Intelligence Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 1983, pp. 6–11. JSTOR

Alan Turing, Enigma, and the Breaking of German Machine Ciphers in World War II

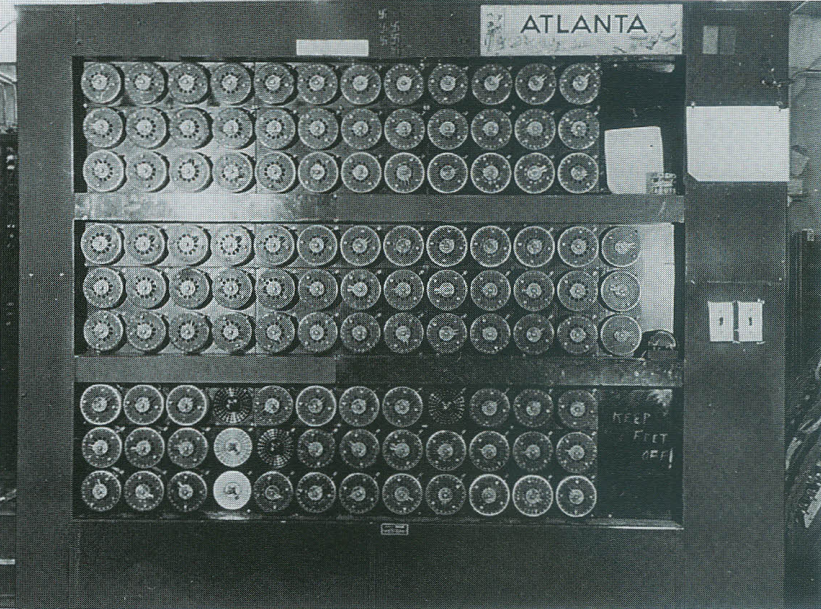

"Six and a half feet high, seven feet wide,

weighing a ton, and perpetually leaking machine

oil, it contained thirty Enigma machines

drivenfrom a common shaft. The

rotors were not positioned side by side

as in an actual Enigma, but rather were

individually mounted flat against

the face of the cabinet."

Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits : The Complete Story of

Codebreaking in World War II. New York, Touchstone Book, 2002

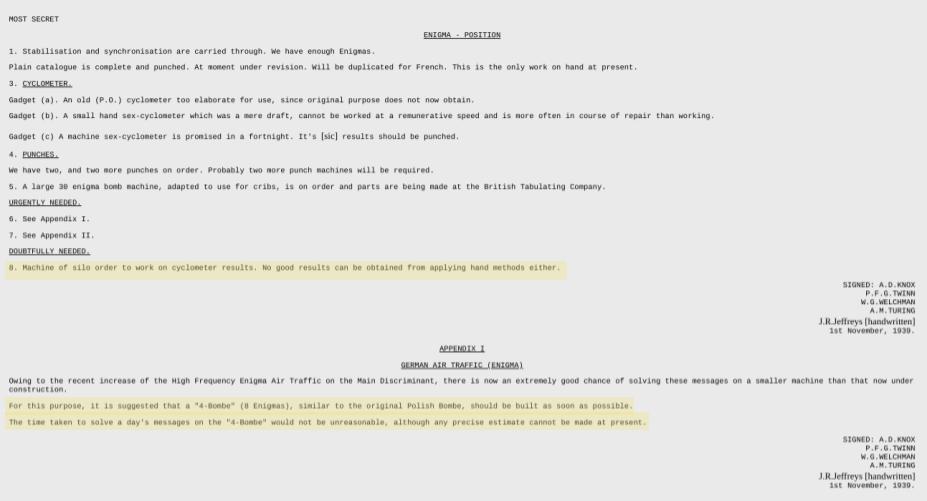

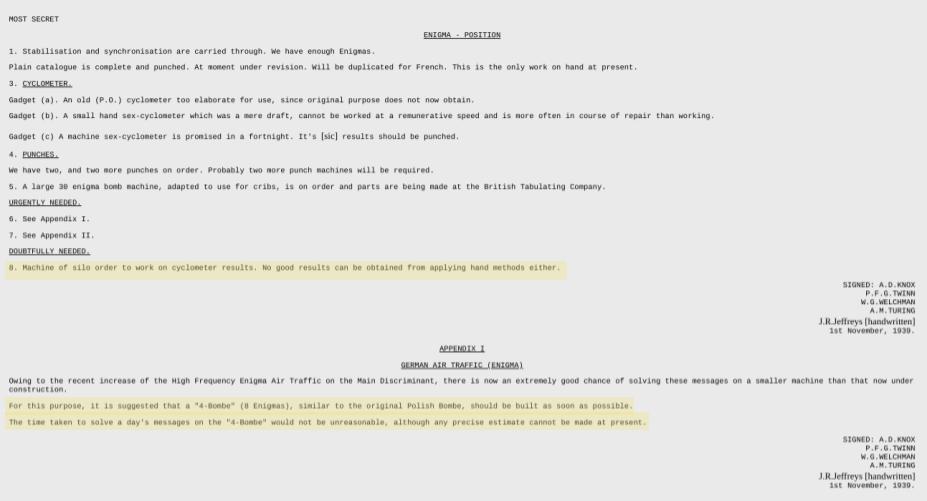

Turing's Treatise on the Enigma describes

his understanding of the code and the bombe’s Polish roots.

Turing, Alan. "Turing's Treatise on the Enigma." 1940.

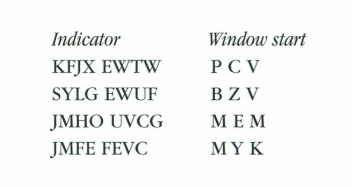

"... repetition of the EW combined with the repetition of V suggests that the fifth and sixth letters describe the third letter of the window

position, and similarly one is led to believe that

the first two letters of the indicator [JM] represent the first letter [M] of the window position, and

that the third and fourth represent the second."

Alan Turing, Enigma, and the Breaking of German Machine Ciphers in World War II

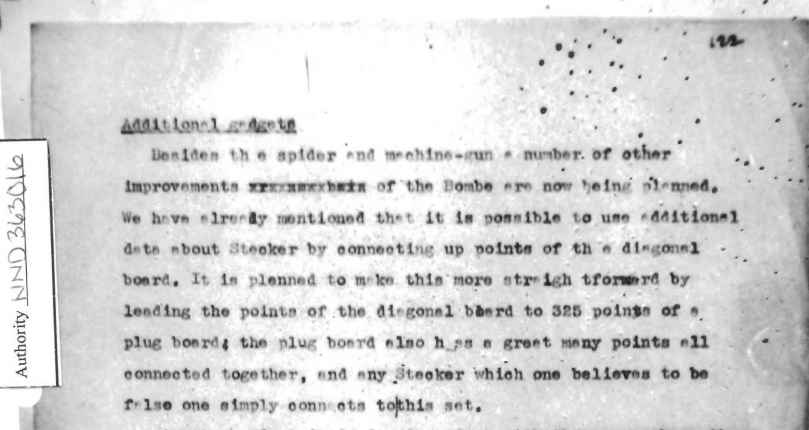

Turing describes plans - bombe additions:

Turing, Alan. "Turing's Treatise on the Enigma." 1940.

Batey describes Turing’s breakthrough:

“the wonderful bombe, and Turing, and everything that came as a result

of exploiting the original breaks." - Batey (Film 12)

Batey, Mavis. "Mavis Batey - Film 3, 4, 10 ,12."

Legasee.org.uk, Netfrux Technologies

"Gordon Welchman Codebreaker."

Crypto Museum, 19 Apr. 2018

Gordon Welchman, head

of Hut 6, improved

Turing's bombes with

“diagonal boards,” ensuring

plausible plugboard

setting eliminations in

one pass, hence

"Turing-Welchman" bombe.

“[Turing] was incredulous at first, as I had been, but when he had studied my diagram

he agreed that the idea would work, and became as excited about it as I was.

He agreed that the improvement over the type of Bombe that he had been

considering was spectacular." - Gordon Welchman

"Enter Turing and Welchman." Bombe.org.uk, www.bombe.org.uk/enter-turing-and-welchman/

Turing’s bombe used algorithmic techniques to speed logical deductions, signaling early major-scale applications of analytical machines to human labor.

"The analyst could select a 'menu' of some ten or so letters from the 'crib' sequence - not necessarily including a 'loop,' but still as rich as possible in letters bound to lead to implications for other letters. And this would provide a very severe consistency condition, sweeping

away billions of false hypotheses with the speed of light.”

Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing - the Enigma. Princeton, New Jersey, Oxford : Princeton UP, 2014.

WRNS used menus for operating bombes. Bombes were so essential to code breaking, they ran 24-7.

"We just operate the bombes full stop, you know. ... You start the bombes, and then they

would go through all these different numbers until they got a possible combination. The

bombe would stop and would write down the first three letters and what the color bombes

were and so forth. Of course nine times out of ten they were no use, and they were just

carried on. You just went on doing it and doing it and doing it." - Joy Aylard

"Joy Aylard - Film 4." Legasee.org.uk, Netfrux Technologies

Bombes facilitated cipher decryptions, giving Allies German information while greatly reducing human codebreaking.

"It would be an understatement to say that the bombes had a great impact on the course

of British (and, later, American) military operations. By providing a method to identify the

‘daily settings' of the Enigma machine used to encipher a particular message (e.g. the naval

version of the Enigma used by the German submarine command), the bombes allowed the

codebreakers into the message. Perhaps the most dramatic result of this success was the

ability (with some interruptions) to track and anticipate the movements of German

submarines during the Battle of the Atlantic."

Alvarez, David. E-mail interview. 2 Feb. 2020.

Alan Turing in 1934. 1934. Duncommutin,