“And we couldn’t have managed without the Bombes because when so many messages were coming in in a day, you couldn’t have people just working on it each individually. It would be nonsense” - Batey (Film 3)

Batey, Mavis. "Mavis Batey - Film 3, 4, 10 ,12." Legasee.org.uk, Netfrux Technologies

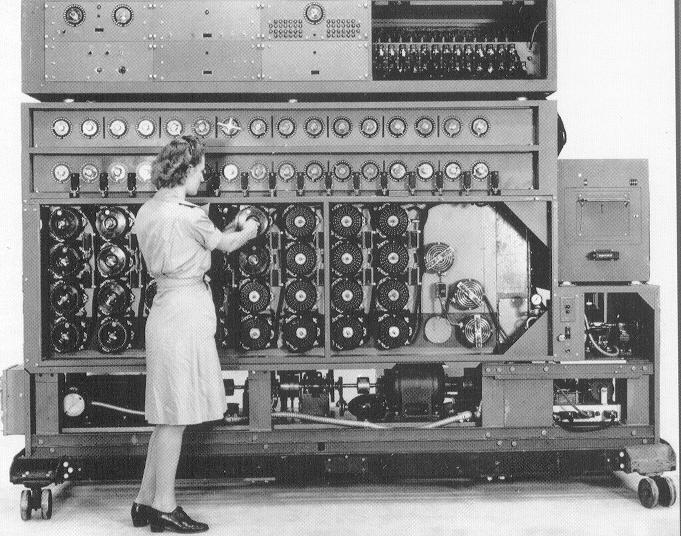

Britain employed the use of machines to complete codework where human hands failed. Similarly, German forces placed trust in their “unbreakable” mechanical code. Furthermore, Turing believed a machine could imitate another. Little did he know, World War II's bombe and Enigma usages broke barriers into modern-electronic ages, majorly replacing complex human thinking and work with machine functions.

"all [Enigma's] intricacies, which taxed the brains of the experts at the time, could now be solved by a [machine] within minutes." - Prof. Garlinski

Bateman, Gary M. "THE ENIGMA CIPHER Machine." American Intelligence Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 1983, pp. 6–11. JSTOR

Ambrose, Stephen E. "Eisenhower and the Intelligence Community

in World War II." Journal of Contemporary History, vol.

16, no. 1, Jan. 1981, pp. 153-64. JSTOR

Another facile error, induced by inertia, is to

permit Ultra to become a substitute for analysis

and evaluation of other intelligence... Ultra

must be looked on as one of a number of

sources; it must not be taken as a neatly

packaged replacement for tedious work

with other evidence." - Col. Taylor

Mans, James. Alan Turing's Office

in Hut 8, Bletchley Park.

"It should not be necessary to stress the value of the material in shaping the general Intelligence of the war. Yet it should be emphasized from the outset that the material was dangerously valuable not only because we might lose it but also because it seemed the answer to an Intelligence Officer's prayer. Yet by providing this answer it was liable to save the recipient from doing Intelligence. Instead of being the best, it tended to become the only source. There was a tendency at all times to await the next message and, often, to be fascinated by the authenticity of the information into failing to think whether it was significant at the particular level at which it was being considered."

Mead, Richard. The Men Behind Monty. Barnsley, Pen & Sword Military, 2015.

Germans fell under this mechanical spell in their pride of their Enigma code, disregarding possibilities of fallibility.

"The basic notation is that one can even make the encryption method public, and just make sure that there are too many combinations for any computer to run through in a reasonable length of time. So in some ways, the Germans actually paid a price for being pioneers; they adopted machine ciphers too early, committing themselves to a design that even as it strode into the new cryptographic age kept one foot dragging behind in the old."

Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of wits : The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York, Touchstone Book, 2002.

Bombes facilitated the institution of mechanizing human work.

Crypto Museum. "History of the Enigma." CryptoMuseum.com, edited by Crypto

Museum, Crypto Museum, 27 Jan. 2019

"The theoretical foundations for the modern computer, and its practical application for business, intelligence and defence purposes, were laid in both Britain and the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. The site bears witness to the first time in history that, spurred on by the exigencies of war, digital technology was harnessed on a systematic basis to the production of information as a commodity."

The International Value of Bletchley Park. Historicengland.org.uk

"But the idea of building machine to solve our problems, an idea that

characterizes our information age society, owes much to Turing's pioneering

efforts, both theoretical and practical."

"Breaking the Code: From the Play Breaking the Code, by Hugh Whitemore: Act II, Scene 7." Bulletin of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 64, no. 4, 2011, pp. 22–30. JSTOR

Passport Sized Photograph of

AMT. Turingarchive.org

Sperling, Karsten. Enigma Machine at the

Imperial War Museum, London. Imperial War Museum, 31 Dec. 2004