Chicago teachers faced deteriorating respect, conditions, and salaries before and during the Great Depression, inspiring their future strikes.

Chicago’s pre-Depression teachers’ unions, including the Men Teachers Union, Federation of Women High School Teachers, Elementary Teachers Union, and the Chicago Teachers Federation, were separated by gender, grade taught, and goals, (Hagopian, 2012), weakening their communication and power (Lyons, 2008).

Margaret Haley once called Mary Herrick, president of the FWHST, “a cheap little nincompoop (Lyons, 2008)” and Agnes Clohesy, leader of the ETU, “a deliberate rascal… She was a personal promoter of herself. She’d walk over her dead relatives and dead friends to get a place (Lyons, 2008).” Herrick called Haley “impossible to get along with,” having an “unwillingness to cooperate in any activity she could not control (Lyons, 2008).”

“It should be borne in mind that the Chicago teaching staff is dominated by women,” said journalist Howard Smith (Smith, 1931,

as qtd in Lyons, 2008). A motorist once yelled at demonstrating female teachers to “go get a husband!” (Lyons, 2008)

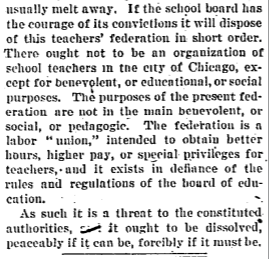

Jacob Loeb, the President of Chicago’s Board of Education at the time, called teachers' unions, “inimical to proper discipline, prejudicial to the efficiency of the teaching force, and detrimental to the welfare of the school system (Loeb, 1915, as qtd, Lyons, 2008).”

(“THE TEACHERS' FEDERATION,” 1905)

Their lack of public respect was largely attributed to the teacher workforce predominantly consisting of women (Lyons, 2008), as well as public figures communicating disdain for teachers in the news and the teachers’ squabbling. Their reputation worsened, aggravating their pre-Depression powerlessness .

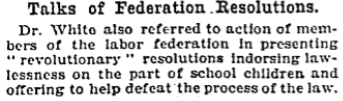

(“TEACHERS' UNION ON RACK: SCHOOL TRUSTEE WHITE ASSAILS THE ORGANIZATION,” 1905)

“... the idea that teaching was a noble profession, free and immune from the cares of a more sordid world, was still prevalent in

the minds of many teachers. As teachers, they felt that they had to maintain a professional dignity, had to be blameless and

subservient, and had to be neutral to social, economic, and political matters (Bessie Slutsky as qtd in “The Chicago Teacher Revolt

of 1933”, 2012).”

“[o]ne of the few compensations of teaching in that time seemed to be a teacher’s consciousness of a certain social superiority over her non-teaching neighbors (Margaret Haley as qtd in Lyons, 2008)”

Teachers’ unions internalized professionalism to gain autonomy, respect, pay, and improved conditions (Lyons, 2008). Educators lobbied, petitioned (The Chicago Teacher Revolt Of 1933,” 2012), and formed connections (Hagopian, 2012) to seem “professional”, eschewing the kinds of strikes seen today (Lyons, 2008).

This 1920s CTF meeting greatly differs from modern pictures of teachers protesting (Rousmaniere, n.d.). They disliked striking, instead acting “professionally”. The CTF, a female-founded elementary teachers’ federation that fought for women’s rights and educational reform, is regarded as the CTU’s predecessor (“Chicago Teachers Union,” n.d.). Note that all these teachers are white. The CTU has a rocky history with race.

Teachers sorely needed the benefits of a professional status, since Chicago’s public schools were mainly funded by property taxes that powerful corporations seldom paid (“The Chicago Teacher Revolt Of 1933,” 2012).

“Too many city classrooms still resemble enlarged prison cells and in too many bad taste is rampant

(George Stayer as qtd in Lyons, 2008).”

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, Chicago was broke (“The Chicago Teacher Revolt Of 1933,” 2012) because of severe financial mismanagement (Rury, n.d.). This, along with tax-dodging and a dramatic increase in enrollment, made public schools’ resources quickly deplete. Working conditions for teachers became near-inhospitable as funding and space dried up (Hagopian, 2012).

Teachers were often laid off or overworked and underpaid. On rare instances where they were paid, they received “scrip” to be cashed in to banks that infrequently observed its full value (“The Chicago Teacher Revolt Of 1933,” 2012).

“Homes have been lost. Families have suffered undernourishment, even actual hunger. Their life insurance cashed in, their savings gone, some teachers have been driven to panhandling after school hours to get food (The Nation, 1933, as qtd in Hagopian, 2012).”

Teachers owed it to their “professional self-respect” to oppose the appalling school conditions, including “mass instruction and mechanization” that “seems to many teachers a deliberate attempt to secure order by mechanizing instruction, reducing the teacher to an automaton, and the pupil to a memory machine (Marian Lyons, 1927, as qtd in Lyons, 2008).”

By 1933, teachers realized that the promises of professionalism went unfulfilled, with their school conditions only getting worse and their cautious union leaders continuing with non-militant actions. The teachers’ disappointment led to the realization that they needed a different approach, leading to the formation of a militant and successful union that led radical protests for well-deserved pay. (Lyons, 2008).