“Protest Restrictive Covenants” (A Just Chicago)

(Stoddard 1963)

“Buchanan v. Warley wherein racial zoning by a municipality was struck down as unconstitutional, with the Court there making the point that racial zoning has no relevancy ‘to the public health, safety, moral, or general welfare.’” (Scanlan 1949, 169). This ruling spurred the use of covenants because of its distinguishment between publicly enacted zoning ordinances and privately enacted restrictive covenants.

|

“Tovey v. Levy...involved a residential building at 417-421 W. 60th Street in the Englewood neighborhood... The contested property had been converted to a rooming house and leased to Joseph Allen, an African American, who rented its thirty rooms to African Americans. Several of the covenant signers sued...The Chief Justice of the Superior Court...issued a decree...supporting the covenant because of rulings of lesser judges involved in the case.” (Plotkin 2001, 57-58)

|

|

“Carl Hansberry [an African American]...twice challenged the Washington Park covenant...With the University of Chicago financing a good part of the suit against Hansberry, the Cook County and Illinois State Supreme Courts ruled in favor of enforcing the covenant...In the November 1940 decision in Hansberry v. Lee, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the lower courts’ rulings.” (Plotkin 2001, 42)

|

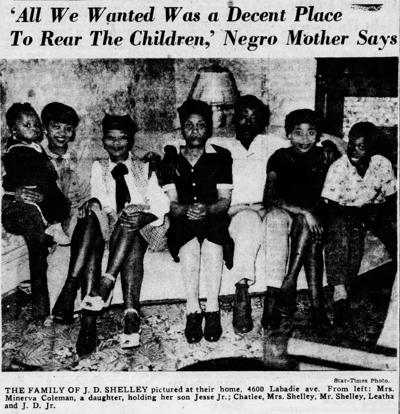

“Shelley v. Kramer...the ruling against the enforcement of covenant--a significant victory not only because of the blow against covenants but because of the new doctrine that the 14th Amendment prohibited state enforcement of racially discriminatory private agreements.” (Plotkin 2001, 54)

World War II’s end brought an increased interest in civil rights movements and consequently, the eventual outlawing of restrictive covenants. Organizations such as the NAACP voiced their contempt for restrictive covenants, causing covenants’ legality to be questioned.

“...restrictive covenants began to fall under withering ideological attack. They were denounced as ‘uneconomic, undemocratic, and unethical,’ and the city’s black press wondered aloud if Americans were going to ‘de-nazify’ their racial beliefs by doing away with such agreements. The mobilization of anticovenant feeling peaked as the war drew to a close and culminated in a series of large public gatherings. The Chicago chapter of the NAACP, the CHR, and the CAD each organized anticovenant parades and conferences. As a result, although covenants were still legally enforceable until May 1948, their open or tacit support became a risky proposition for those in the public eye.” (Hirsch 1983, 178)

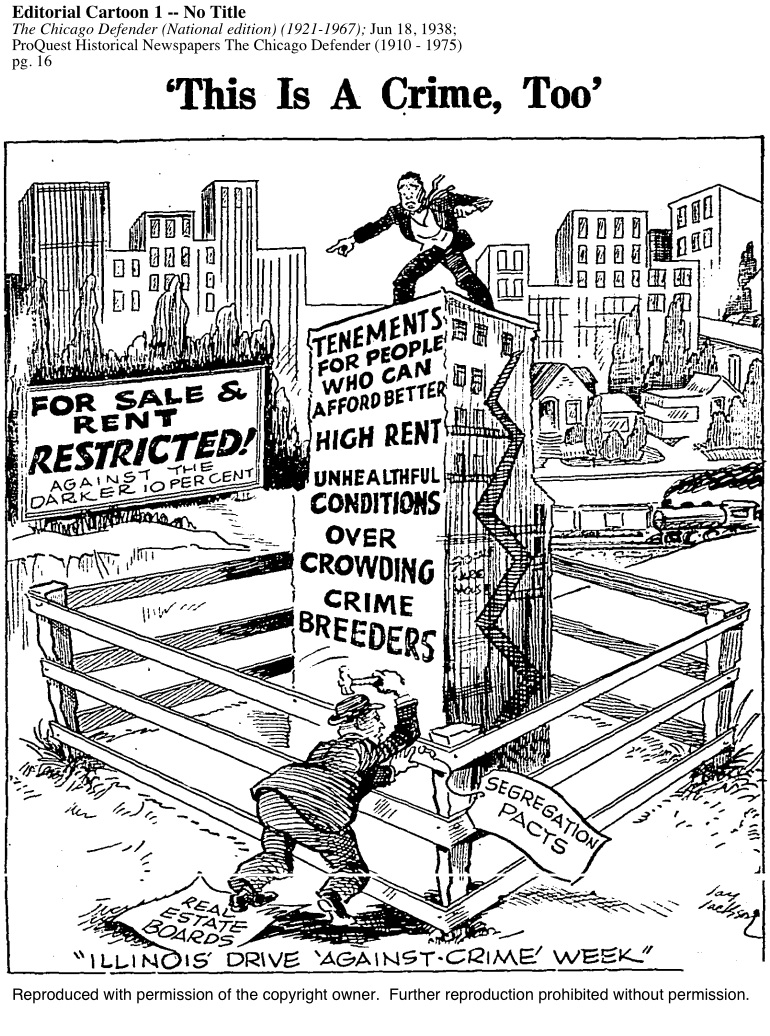

(The Chicago Defender 1938)

Black Chicagoans pursued various methods of breaking down the barriers of residential segregation. From individuals purchasing homes in previously all white neighborhoods, to legal organizations attacking the laws that made covenants judicially enforceable, Black Chicagoans began the process of ending racially restrictive covenants.

“Protest Restrictive Covenants” (A Just Chicago)

Chicago’s NAACP Conference in 1944 (The Encyclopedia of Chicago 2005)

“NAACP was also pressing its legal campaign against restrictive covenants, pursuing the Lee v. Hansberry case in the ultimately successful attempt to open up the Washington Park Subdivision.” (Hirsch 1983, 176)

(Chicago Defender 1940)

“...as they grew increasingly confident of the experience and expertise of the Chicago branch of the NAACP to defend them, African Americans continued to move in large numbers into covenanted neighborhoods and dared white owners to enforce the covenants.” (Plotkin 1998, 46)

“As vacancies began to appear around established black communities in the late 1940s and 1950s, black ‘pioneers,’ eager to escape ghetto conditions and both willing and able to compete economically for the inner-city housing becoming available, moved into previously all-white neighborhoods.” (Hirsch 1983, 28)

“Shelley v. Kraemer” (St. Louis Post-Dispatch )

Racially restrictive covenants were deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1948. Although they still contributed slightly to residential segregation post their outlawing, as many realtors and individual sellers continued to follow them, the peak of restrictive covenants’ effectiveness had passed. However, the sentiments behind covenants continued to pervade Chicago. Now, instead of employing restrictive covenants as their main tool of enforcing segregation, private institutions and homeowners turned to new methods.

(Chicago Defender 1948)