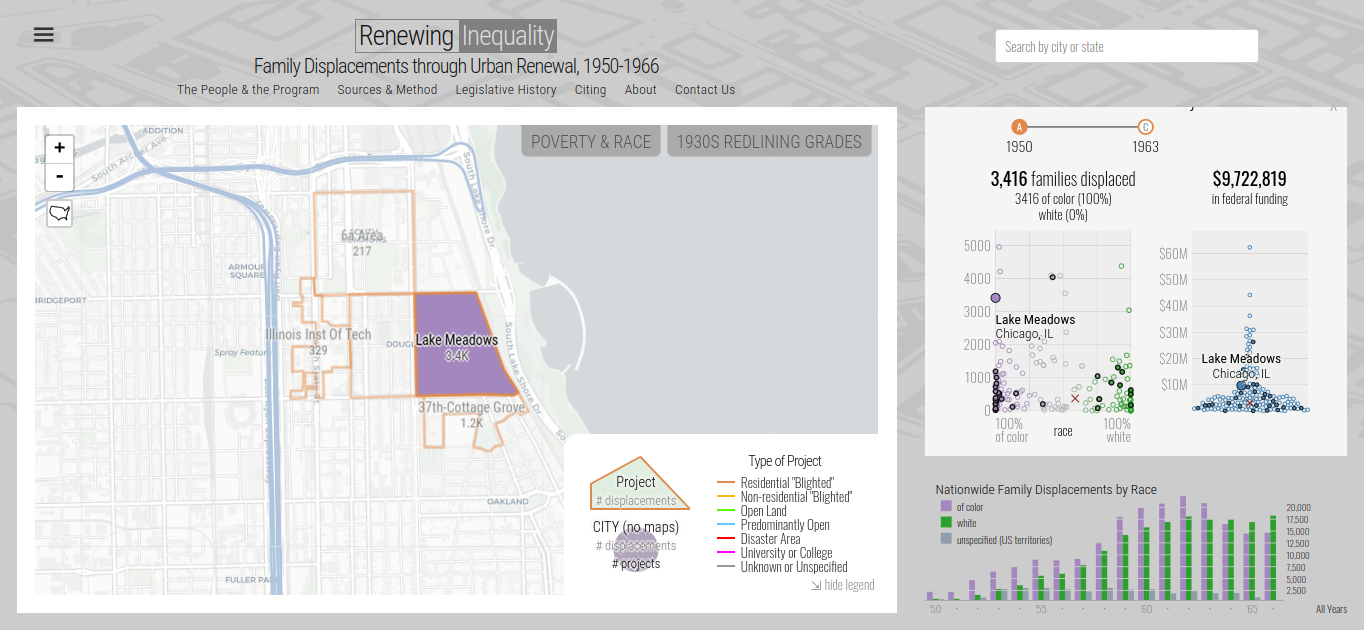

“Chicago’s business elite clearly envisaged a postwar building boom on the city’s periphery, the flight of the middle class, and the insulation of State Street from its ‘normal market.’ They subsequently tried to counter the forces promoting decentralization through the ‘complete rehabilitation of the center of the city.’” (Hirsch 1983, 101)

(The American Title Association 1951)

Mayor Richard Daley and former Mayor Martin Kennelly, two key mayors who were crucial to the urban redevelopment plans (Chicago Tribune)

Marshall Field and Company Building circa 1907 (Library of Congress via Time Out Chicago)

“Together, Pettibone, Mumford, and the MHPC devised a redevelopment formula based on private profit and public power and saw their program accepted by both Mayor Martin H. Kennelly and the state legislature.” (Hirsch 1983, 102)

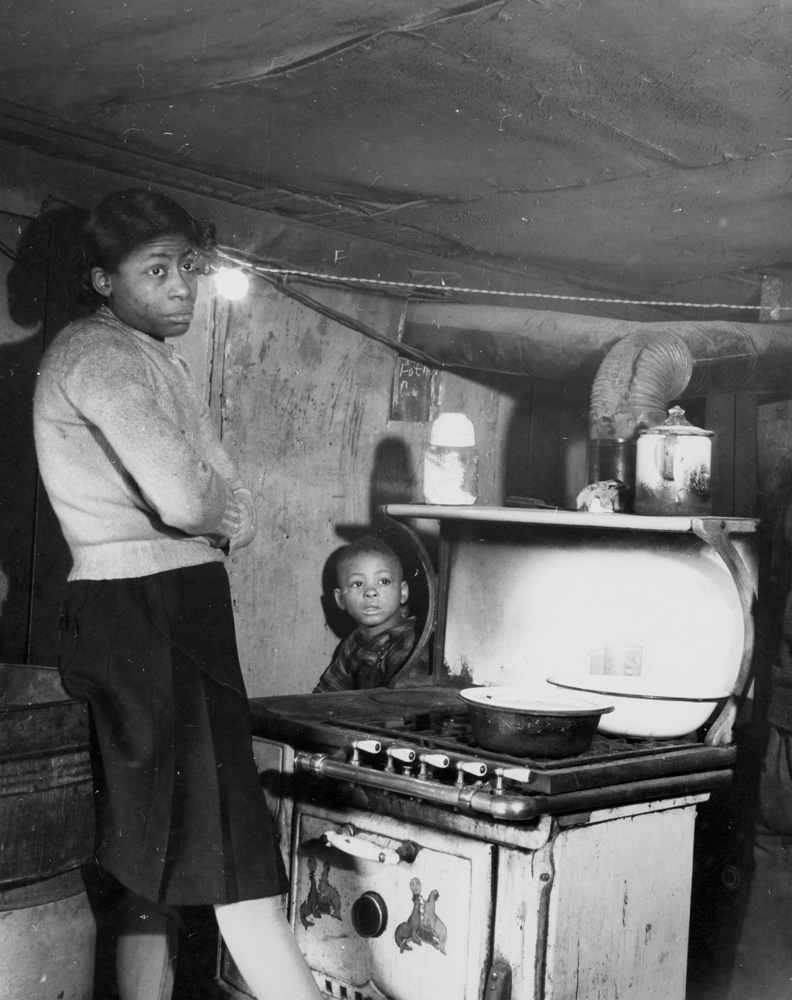

“The crucial point was that the Chicago Housing Authority, which operated publicly owned housing, had a nondiscriminatory tenant selection policy. Under the 1947 legislation, however, redevelopment projects would be privately owned and thus exempt from CHA restrictions.” (Hirsch 1983, 110)