Zimbaro remembers the turning point within the study, where he realized that, "these were real boys who were really suffering. And that fact had escaped me. I and everyone else around me except for that graduate student--had gotten so far into their prison role prisoner, guard, superintendent, whatever that it was hard to separate reality from the simulation."

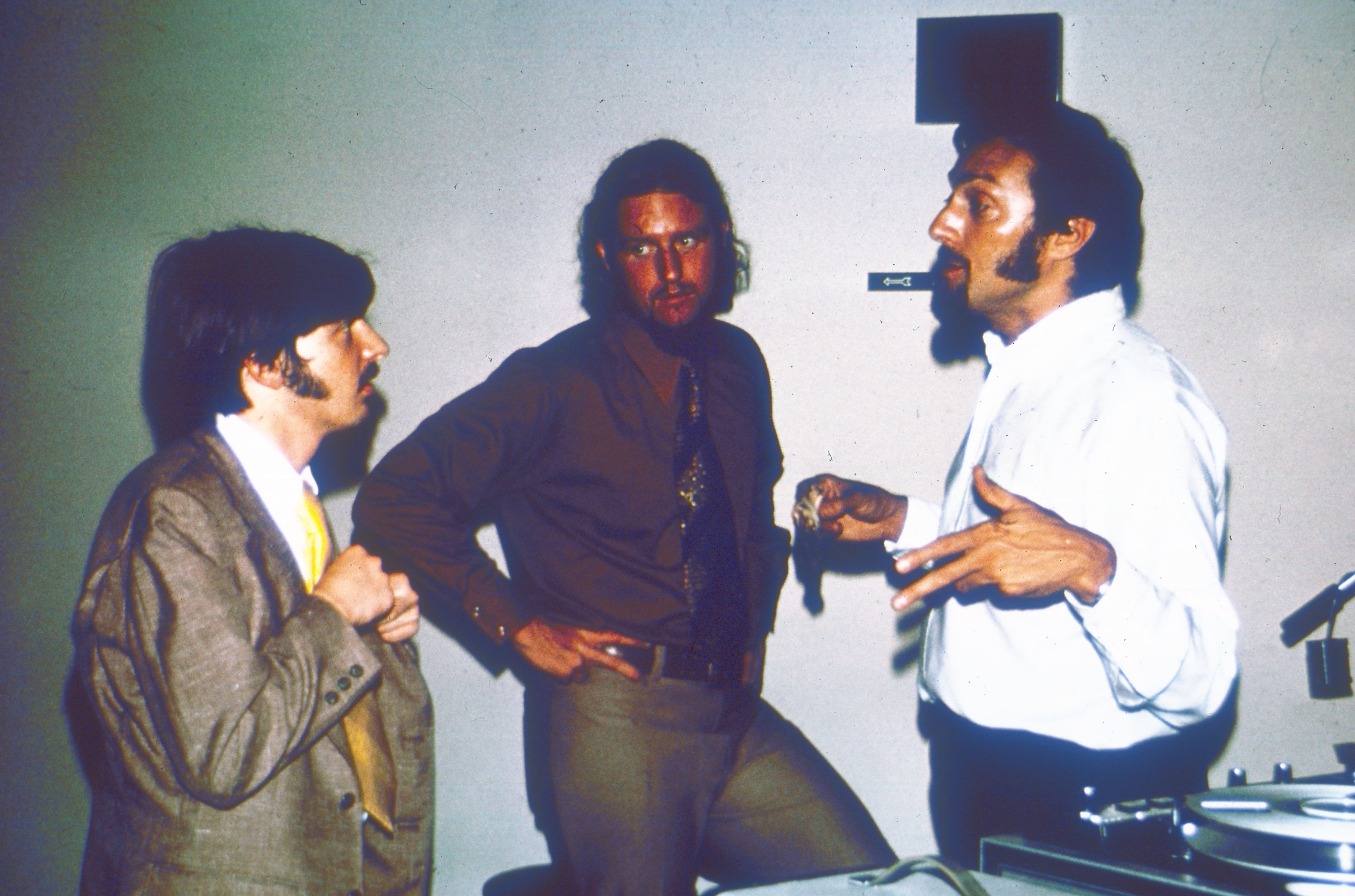

Phillip Zimbardo, Quiet Rage.

Zimbardo interfered by giving the guards instructions during their orientation. He told them, "we can create boredom. We can create a sense of frustration. We can create fear in them, to some degree. We can create a notion of the arbitrariness that governs their lives, which are totally controlled by us, by the system, by you, me, Jaffe. They'll have no privacy at all, there will be constant surveillance—nothing they do will go unobserved. They will have no freedom of action. They will be able to do nothing and say nothing that we don't permit. We're going to take away their individuality in various ways."

Phillip Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect, Pg. 55.

During visiting day, Zimbardo interfered with the study by improving the treatment of the prisoners, in order to prevent them from complaining to their families about the bad conditions in which they were subjected to. Zimbardo shares, "we first grossly manipulated the situation, and then we subtly manipulated the visitors. We did the "hypocrisy" trip to make the prison environment seem pleasant to the parents and undercut any complaints the prisoners might present to them. We washed, shaved and groomed the prisoners, had them clean and polish their cells; we removed all the signs, fed them a big dinner, played music on the intercom, and even had an attractive co-ed, Susie Phillips, greet the visitors at our registration desk."

Phillip Zimbardo, The Stanford Prison Experiment, Pg. 8.

Not only was his interference unethical, it hurt the experiment. After receiving a warning that the prisoners were planning a potential escape, Zimbardo recalls, "we had spent one entire day planning to foil the escape, went begging to the Police Department, cleaned up the storeroom, moved our prisoners, dismantled most of the prison, we didn't even collect any data during the entire day."

Phillip Zimbardo, The Stanford Prison Experiment, Pg. 10

Zimbardo interfered by exaggerating the results of the study. Prisoner 8612 recalls, “the only thing that’s always troubled me through the years is that the experiment is interesting to people like you and the general public because it makes you wonder, you hope that you wouldn’t be a bad person like those sadistic a**hole guards, and so the experiment is compelling and interesting to people because it brings up that issue, oh I hope I wouldn’t be a horrible, nasty person, and that’s the message that Zimbardo wants to send and what's interesting to me about this is that only two of the guards were sadistic, the other eight were not, so why are we talking about the other eight guards that weren’t a**holes, that weren’t sadistic, why are we only talking about the two little horrible guys. And well the reason we’re talking about them is because that’s what interests people."

Douglas Korpi, Interview.