Early BASIC

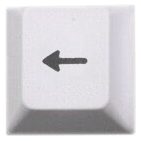

Thomas Kurtz

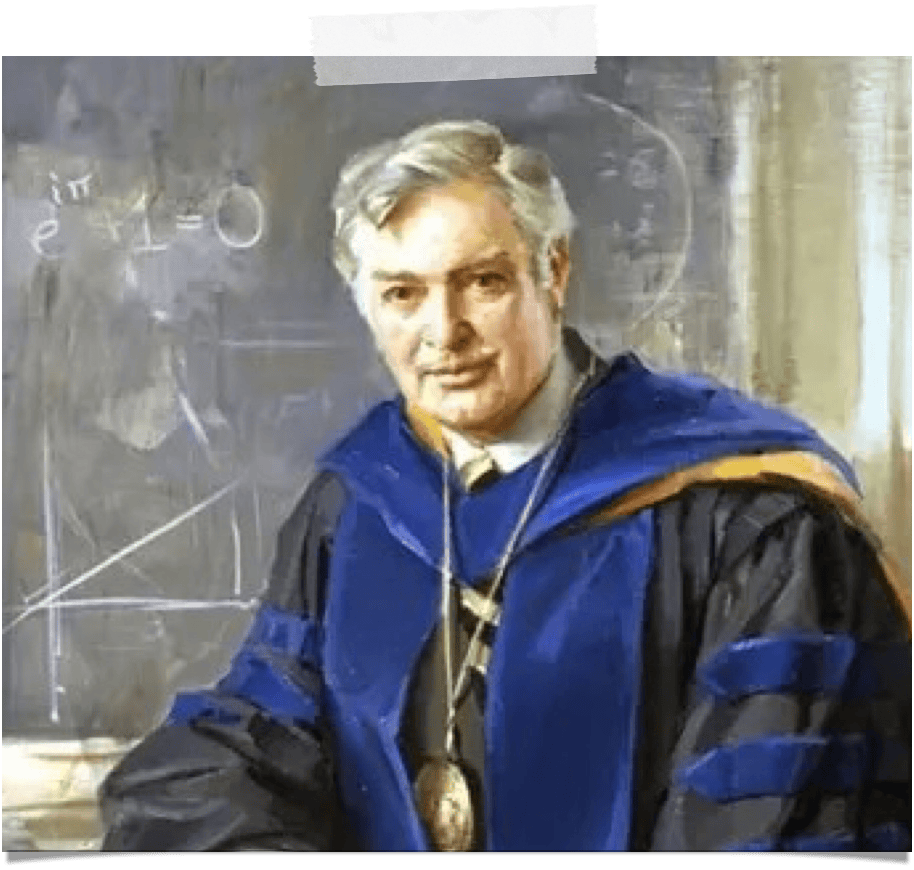

John Kemeny

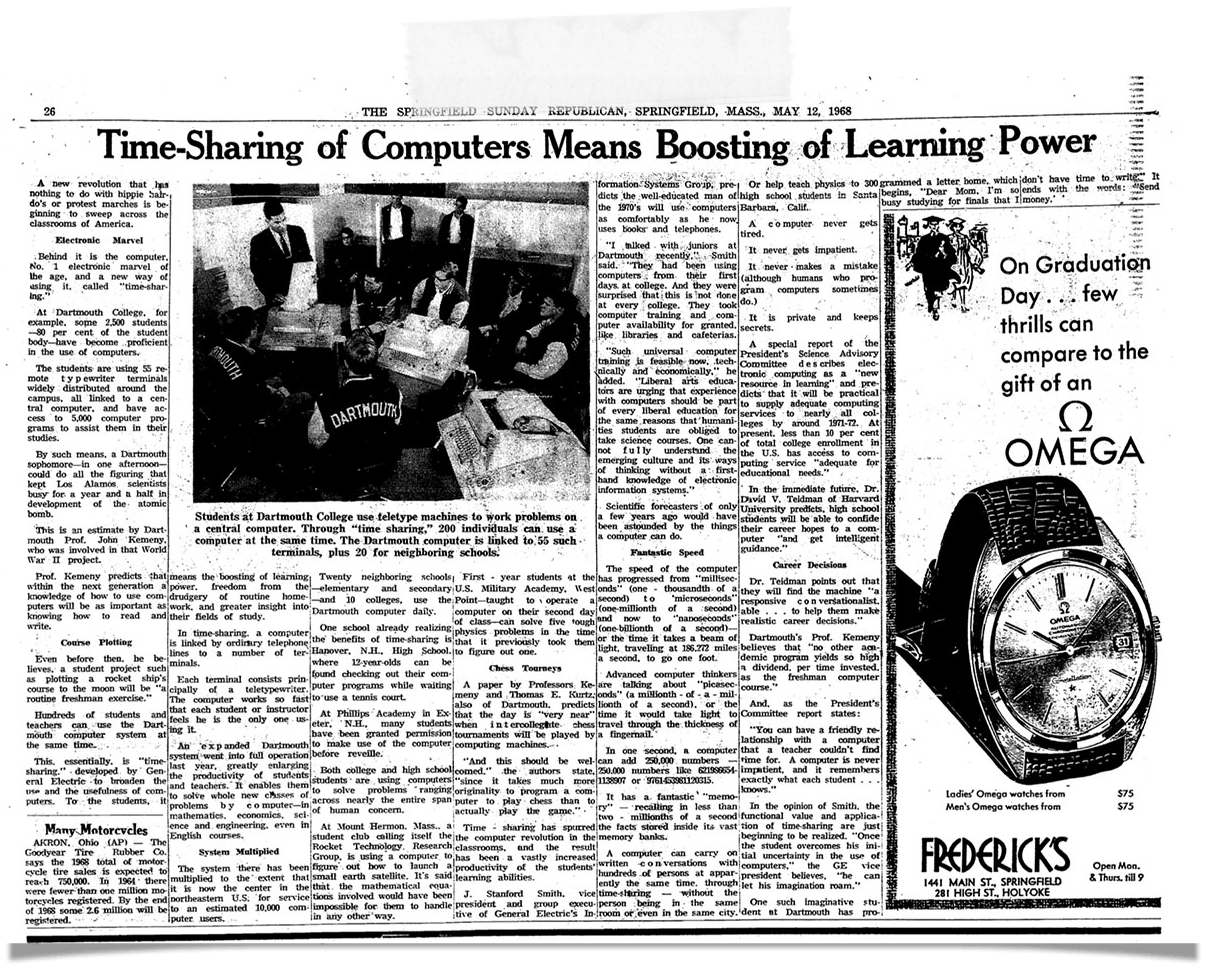

Kurtz was not the first to think of a time-sharing system, where multiple users could concurrently share resources of one computer for instant results. He heard about it during a trip to MIT, where the idea was already being experimented with. However, he was the person who would make it a reality. After that visit, Kurtz explained the idea, and Kemeny latched onto the vision. In fact, Kemeny had never liked the standard of 1950’s and 60’s computing—the extremely high volumes of data could take days to process.

"

Our vision was that every student on campus should have access to a computer.

"

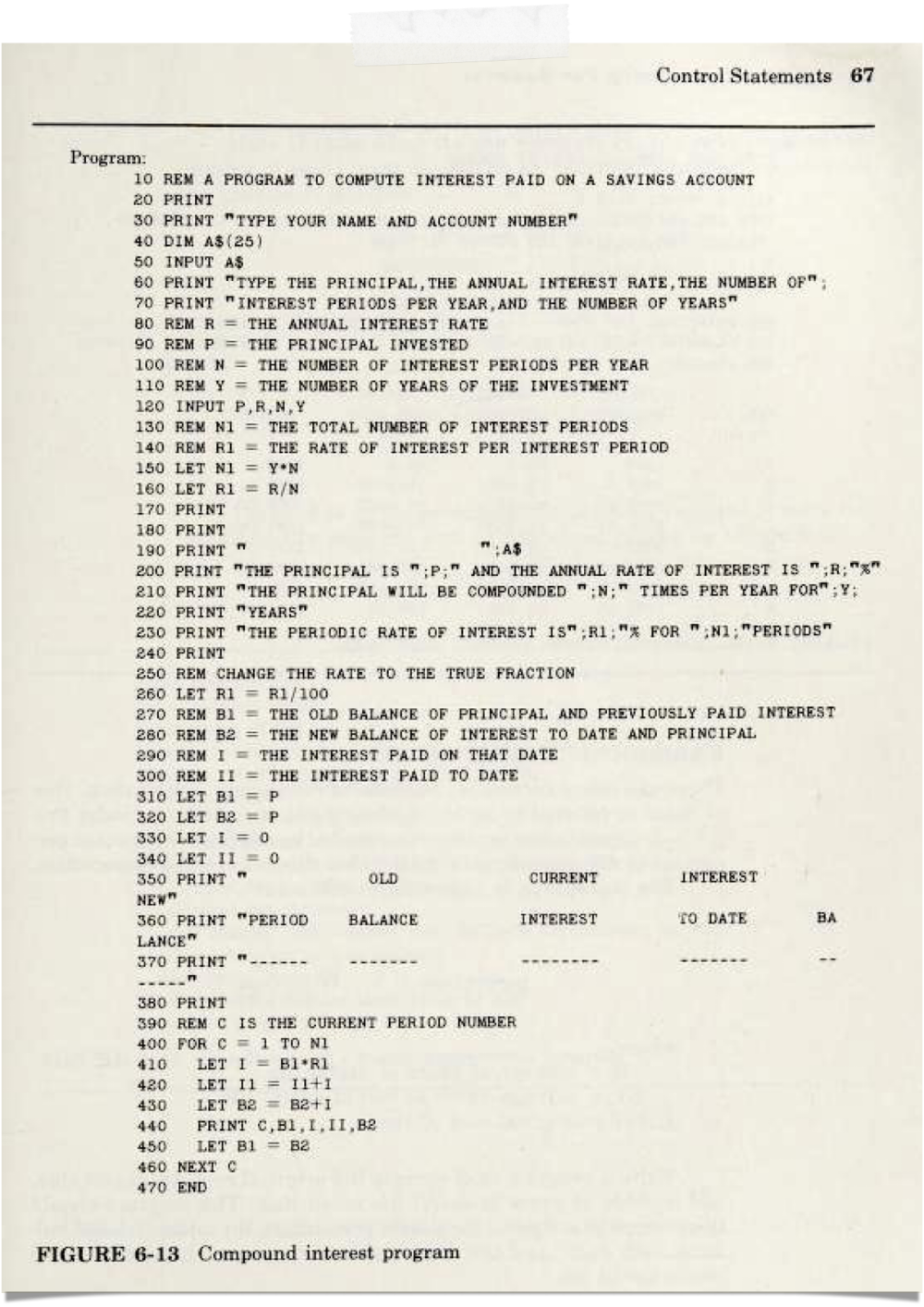

As the time-sharing system, now called DTSS (Dartmouth Time Sharing System) was being created, they had to decide what programming language to use.

Kurtz spoke about the decision later:

“We looked at languages and we both decided that the languages FORTRAN, ALGOL—that type of language were just too complicated. They were full of punctuation rules, the need for which was not completely obvious and therefore people weren't going to remember.”

“I finally decided that [using a previous language] was not possible […] and I agreed with Kemeny that a new language was needed.”

That new language became BASIC, or Beginners All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code. When a compiler was built to run programs and DTSS was set up, it was finally ready to be used. BASIC was not intended to be used commercially—with 15 instructions (later updates would add several more) and very low speed, it was exclusively a teaching language. Really, what made BASIC so great was the same as what made it 'useless' in a practical sense. The ability to learn how to control a computer in an hour or two was previously nonexistent. With such limited resources, trade-offs had to be, and were, made.

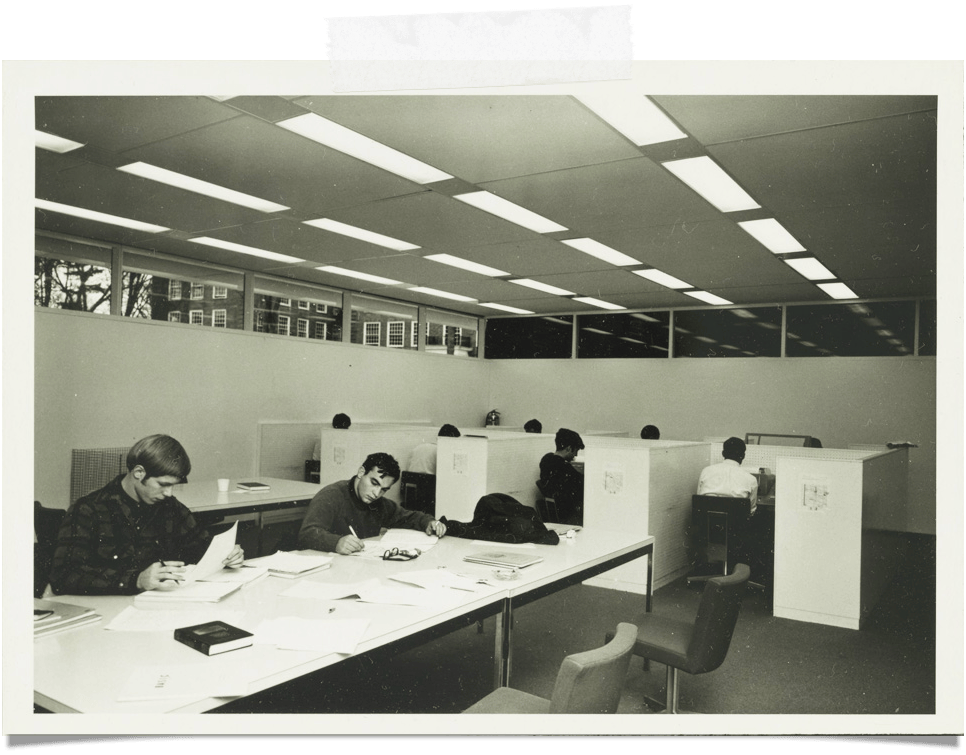

DTSS and BASIC were both huge successes. Many students and teachers started using the system regularly, but the system also spread outside of Dartmouth. Using telephone lines, other schools started to access DTSS and it began spreading across the country.

Kemeny and Kurtz had already achieved more than they had hoped for. In the following years, Dartmouth built a Computer Lab, the Kiewit Computation Center, increasing Dartmouth's reputation in computer fields.