Lead Up

History of Tinkathia System

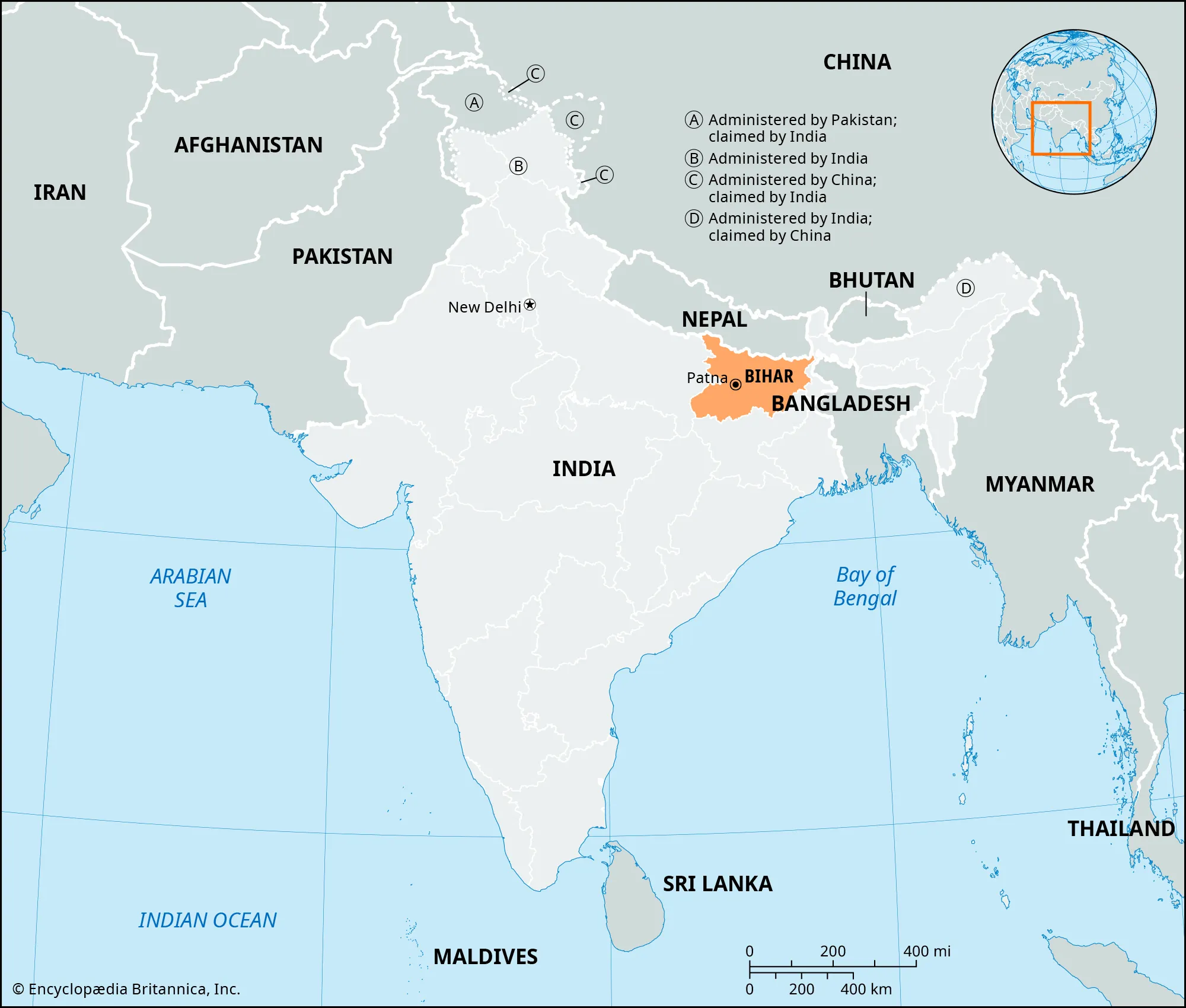

Before the Champaran Satyagraha, European planters abused farmers for over a century under the exploitative Tinkathia System where peasants of Champaran, Bihar were required to plant indigo, used to make blue dye, on their land with no compensation.

(“East Champaran District”)

(Dayal, Bihar, India)

The population of the Champaran district was approximately 2 million people in 1917 (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India), 70% of whom were directly dependent on agriculture for their livelihood (Singh).

The land was owned by Indians until 1793 when the British Empire began its rule. European planters took over from the former owners, forcing peasants (ryots/raiyats) to grow indigo on a portion of their land instead of necessary food (Rennebohm).

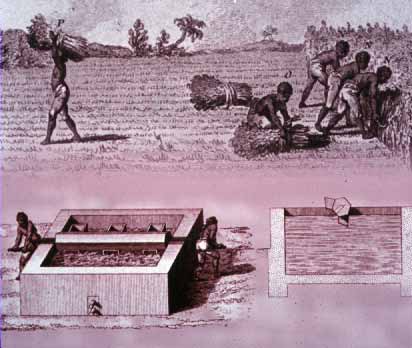

("Indigo & Rice")

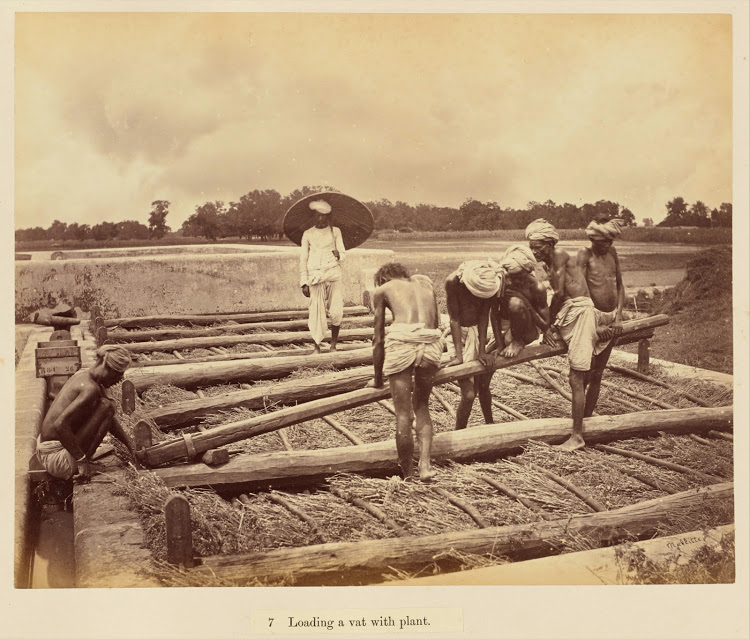

("The Planting & Manufacture of Indigo in India by French Photographer Oscar Mallitte - Allahabad, 1877")

"Starting with indigo it has taken in its sweep all kinds of crops. It may now be defined as an obligation...whereby the raiyat has to grow a crop (indigo) on 3/20th of the holding at the will of the landlord" -Letter, dated Bettiah, 13 May, 1917, from M.K. Gandhi to Chief Secretary to Government of Bihar and Orissa, Banchi (Misra & Jha 127)

Planters beat and imprisoned peasants, increased rent, and imposed illegal taxes. They resorted to inhumane methods to maximize indigo profits with support from the British administration (Remesh).

"Not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained with human blood…I have had ryots before me who have been shot down by the planters” -E. De-Latour, Magistrate of Faridpur in 1848 (Remesh)

(Chelladurai)

Indigo farmers in Champaran working under exploitative plantation conditions during British rule (Saxena)

The ryots' lack of education allowed the planters to manipulate them using lease agreements, forcing them into cycles of debt and food scarcity (Pathak):

“In lease-hold lands they made the raiyats pay…damages…in consideration for waiving their right to indigo cultivation. This the raiyat’s claim was done under coercion. Where the raiyats could not find cash, hand-notes and mortgage bonds were made for payment in installments…these [have] been fictitiously treated as an advance to the raiyat” -Letter, dated Bettiah, 13 May, 1917, from M.K. Gandhi to Chief Secretary to Government of Bihar and Orissa, Banchi (Misra & Jha 127)

The Bihar Planters’ Association (BPA) acknowledged abuses but minimized them and denied fundamental injustice in the Tinkathia System:

“There may be abuses in the work of supervision as those will be found in every human institution, but…these have been grossly exaggerated and planters are European gentlemen who do their best to prevent these...In any case, the raiyat cannot have it both ways, have the great benefits which the cultivation has brought without submitting to the regularity the system demands” -Letter No. J-4164, dated Muzaffarpur, 29/30 June, 1917, from L. F. Morshead, I.C.S., Commissioner of Tirhut Division, to Chief Secretary to Government, Bihar and Orissa (Misra & Jha 283)

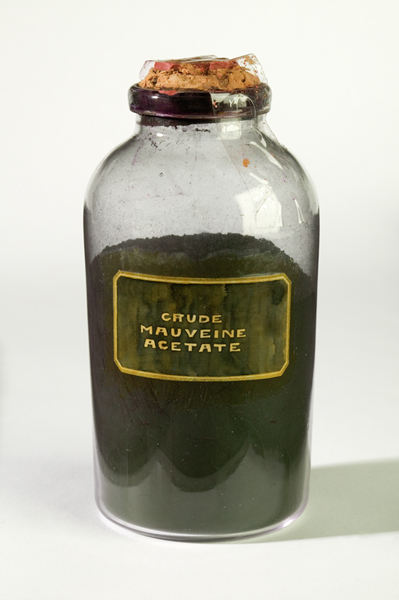

Synthetic Dye Leads to Changes

In 1857, Germany developed synthetic dye, reducing the global demand for natural indigo and devastating communities that depended on its cultivation. By 1870, Germany produced 50% of the world’s synthetic dyes, rising to 85% by 1900 (Zwirn). Indigo became unprofitable, pushing farmers deeper into debt while planters withdrew from contracts that no longer benefited them.

First Synthetic Dye (Hicks)

“When, however, owing to the introduction of synthetic indigo the price of the local product fell, the planters desired to cancel the indigo sattas (contracts)” -Letter, dated Bettiah, 13 May, 1917, from M.K. Gandhi to Chief Secretary to Government of Bihar and Orissa, Banchi (Misra & Jha 127)

The system shifted again during World War I. In March 1915, the British navy blockaded German ports stopping the flow of these dyes to India. Attempts to replace German production failed to meet demand and a massive shortage followed, forcing the farmers to resume indigo cultivation.

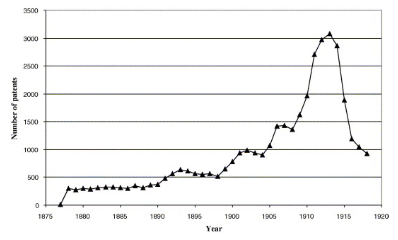

German Dye Production between 1876 and 1920 (Streb & Wallusch & Yin)

Farmers Ask for Help

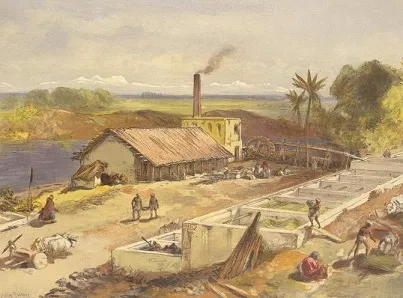

(Hari, Indigo Dye Factory in Bengal, 1850s)

Peasant resistance to indigo exploitation predated Gandhi’s involvement. The Bengal Indigo Revolt of 1859, a peasant revolt against British planters, established the precedent of organized anti-colonial protest and remained a powerful memory among farmers.

Inspired by this history, Raj Kumar Shukla, a Champaran farmer, sought Gandhi’s assistance after learning of his activism in South Africa. Shukla persistently appealed to Gandhi, who although initially reluctant, agreed to investigate and arrived in Champaran on April 9, 1917.

(Joshi, Portrait of Raj Kumar Shukla)