Origins of Common Schooling

[One-Room Lancaster Schoolhouse, Massachusetts Historical Photo Collection]

Free universal education for every American child, at the expense of the government, hasn't always been the norm.

Birth of an Idea

The idea of public education in the Americas was born in Massachusetts — in the 1640s.

Massachusetts had been primarily settled by European Puritans who had graduated from premier English colleges and thus valued literacy and education.

"The English Puritans who founded Massachusetts believed that the well-being of individuals, along with the success of the colony, depended on a people literate enough to read both the Bible and the laws of the land."

(Massachusetts passes first education law, MassMoments)

[Book from ~1642 Colonial Massachusetts School, MassMoments]

To promote literacy, Massachusetts passed the School Law of 1647, implementing public schools in medium and large towns.

"It is therefore ordered that every township in this jurisdiction, after the Lord hath increased them to fifty households shall forthwith appoint one within their town to teach all such children as shall resort to him to write and read, whose wages shall be paid either by the parents or masters of such children, or by the inhabitants in general, by way of supply, as the major part of those that order the prudentials of the town shall appoint; provided those that send their children be not oppressed by paying much more than they can have them taught for in other towns.

And it is further ordered, that when any town shall increase to the number of one hundred families or householders, they shall set up a grammar school, the master thereof being able to instruct youth so far as they may be fitted for the university, provided that if any town neglect the performance hereof above one year that every such town shall pay 5 pounds to the next school till they shall perform this order."

(The Old Deluder Satan Act (School Law of 1647), Massachusetts, 1647)

Barriers

The 1647 Law served as a start for public schooling, but students still faced barriers in receiving an education.

"During the first decade after the 1647 law was enacted, all eight of the 100-family towns and one-third of the fifty-family towns met the respective grammar and petty school requirements: subsequently, however, new towns often ignored both mandates and instead paid the fine."

(Historical Dictionary of American Education, Richard J. Altenbaugh, 1999)

One major problem was that while large cities had the resources for public education, not all small towns did. And some towns could provide schools, but still refused.

"By sad experience it is found that many towns that are not only obliged by law, but are very able to support a grammar school, yet choose rather to incur and pay the fine or penalty than maintain a grammar school."

(General Court, 1718)

Even in towns that followed the mandate, schools often charged tuition. This presented a financial barrier that prevented poorer students' attendance. The only alternatives to these 'common schools' were church schools, which also required tuition.

[Caricature of Primitive New England School, Columbus and Columbia, 1893]

Other barriers to education existed: many students stayed home as schooling was non-compulsory, the education was minimal, and schools were underfunded.

Additionally, girls and nonwhites were often excluded from education, especially from college; these barriers reflected a public belief that education was primarily intended for white males.

"Education, however, was limited to daughters of the elite. These girls had access to tutors and private schools. All women, however, were prohibited from collegiate education." (Historical Dictionary of Women's Education; 'Colonial Schooling' chapter, Linda Eisenmann, 1998)

"Starting in 1787, numerous community members, including Prince Hall, petitioned the state legislature claiming that it was unjust for their taxes to support the education of white children when the city had no school for black children. However, a small number of African American children did attend the city's white schools." (Abiel Smith School, Boston African American History, 2017)

Horace Mann

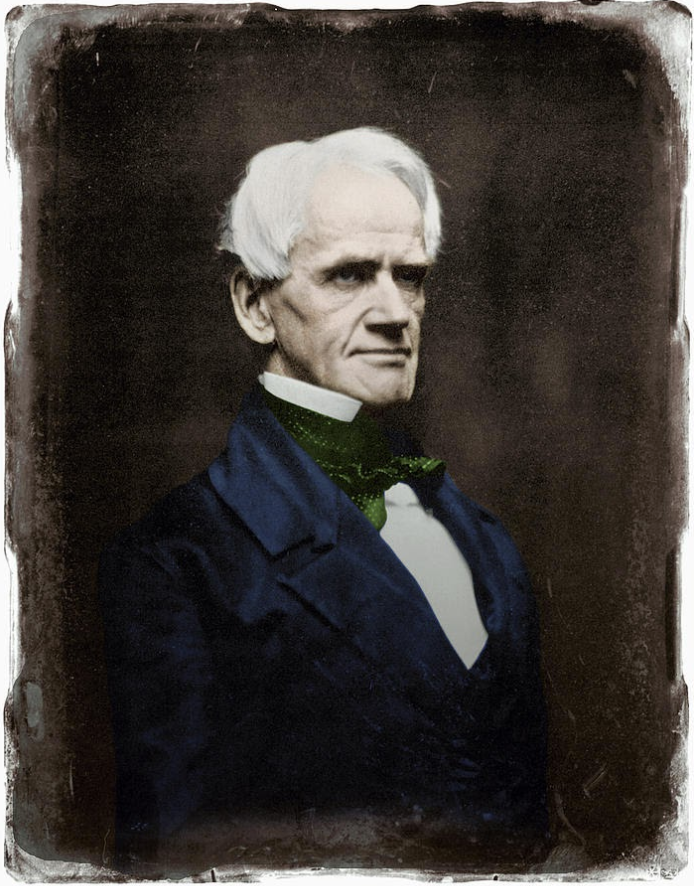

Impacted by a lack of childhood education was Massachusetts legislator Horace Mann. As a child, Mann never received more than six weeks of schooling in a year. He described his instructors as "Very good people, but very poor teachers." (Appleton Encyclopedia of American Biography, Wilson and Fiske, 1887).

Despite these setbacks, Mann was able to self-educate (at public libraries) and earn admission to college in 1816.

[Horace Mann, Colorized, Fine Art America]

Mann's experience of fighting for his education gave him a strong desire to reform the school system when he was elected to the state legislature in 1827.

"Of the many causes dear to Mann's heart, none was closer than the education of the people. He held a keen interest in school policy."

"He worked [on education reform] almost night and day, devoting fifteen hours daily to its demands, holding teachers' conventions, delivering lectures, and keeping up an enormous correspondence"

(Republic and the School: Horace Mann and the Education of Free Men, Cremin, 1957)