Education Reform in Massachusetts

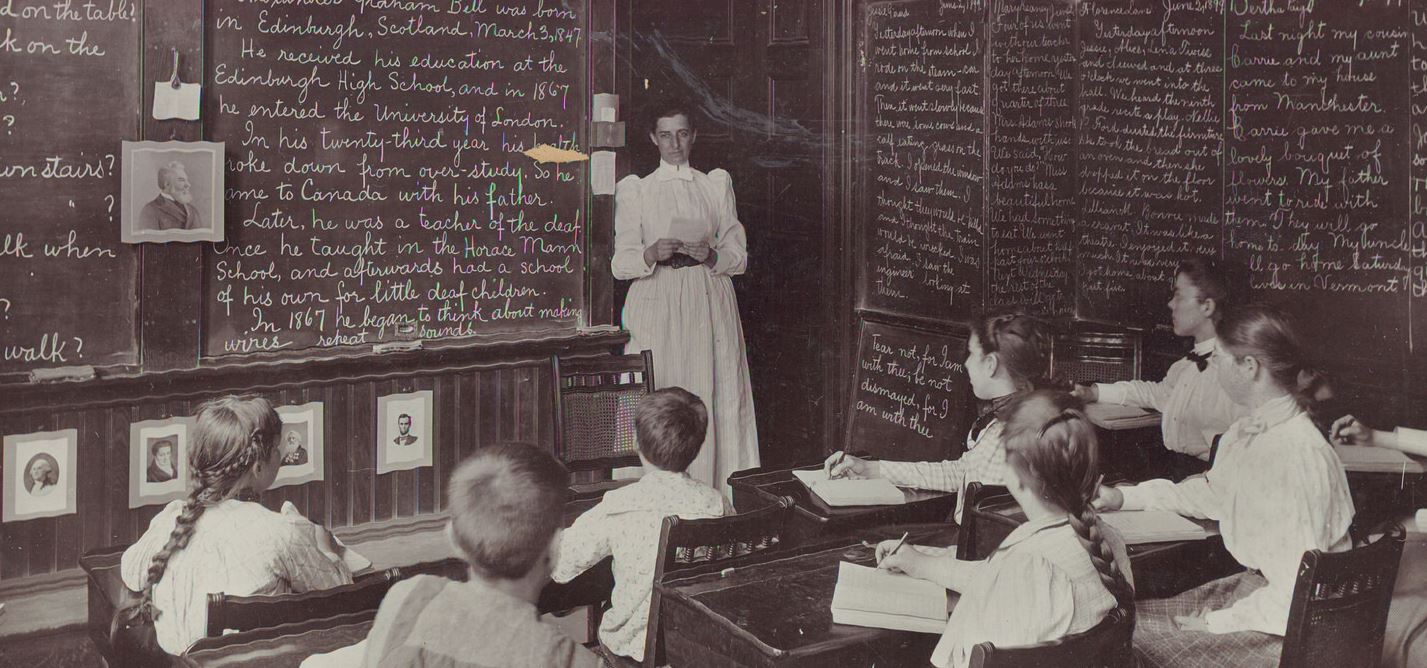

[American Public Schooling, Intellectual Takeout]

Despite opposition to his principles, Horace Mann was able to implement several significant changes in Massachusetts schooling.

Progress

During his tenure, Mann drastically increased public schools’ resources, funded school committees, and established a six-month minimum length for school years.

"Statistics tell us that:

the appropriations for public schools had doubled;

that more than $2,000,000 had been spent in providing better schoolhouses;

that the wages of men as teachers had increased 62 percent, of women 51 percent, while the whole number of women employed as teachers had increased 54 percent;

one month had been added to the average length of the school year;

the ratio of private-school expenditures to those of the public schools had diminished from 75 percent to 36 percent;

the compensation of school committees had been made compulsory, and their supervision was more general and more constant"

(Martin's Ed. in Massachusetts, George Henry Martin, 1894)

Mann's efforts also coincided with an increase in the enrollment of girls in schools in the early 19th century. This happened without much debate, as the country was much more focused on the annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the debate over states' rights pertaining to slavery.

"Starting in Massachusetts and Connecticut through the efforts of Horace Mann, Henry Barnard, and others, local public schooling was organized and systemized for the first time. Girls as well as boys increasingly entered elementary schools."

(Historical Dictionary of Women’s Education, Linda Eisenmann, 1998)

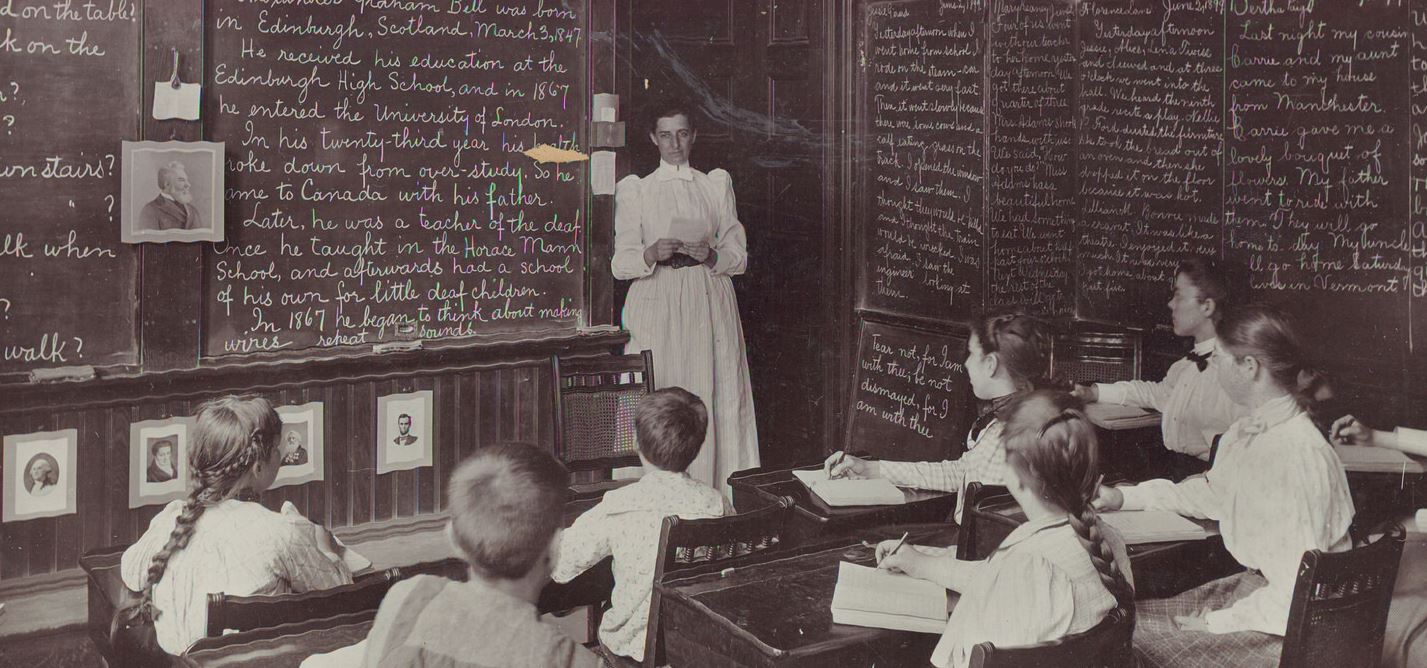

But Horace Mann's most significant undertaking was his establishment of the first public normal schools — academies at which teachers could improve their pedagogical skills.

[First Normal School in America, Lexington, Mass, Boston Public Library, 1930]

Through these normal schools, Horace Mann was able to create a universal standard for teaching, which had a clear impact on the quality of education.

"Three normal schools had been established, and had sent out several hundred teachers, who were making themselves felt in all parts of the state."

(Martin's Ed. in Massachusetts, George Henry Martin, 1894)

A Turning Point

The culmination of all these reforms came with the passage of the Massachusetts 1852 Compulsory Attendance Act.

This act required all children aged 8-14 (with some exceptions) to attend public school for at least 12 weeks per year, with six consecutive weeks.

The act was not as prohibitive as some critics argued. Children who were "otherwise furnished with the means of education for a like period of time" and those who had "already acquired those branches of learning which are taught in common schools" were exempt, allowing private and home schooling. (Compulsory Attendance Act, Massachusetts, 1852)

"Education is the great equalizer of the conditions of men, the balance wheel of social machinery."

[Education is] "an absolute right of every human being that comes into the world."

(Common School Journal, Horace Mann, 1839)

This act's passage showcased that Horace Mann had successfully influenced the population with his vision of universal high-quality education. Although Massachusetts had public schools since 1647, this was the first time in American history that any state had required school attendance. This new system was also unique because the common schools were nonsectarian, whereas the Puritans' schools had clear religious intent.

But there was still room for improvement, as enforcement was weak and school years were short.

[Origin of Compulsory Education, article by Bruno Campello]