INSPIRATION

While working at her job as a manicurist, Bessie’s clients and her brothers would tell stories about French women aviators who served in WWI. Her brothers would often tease her - “Those French women do something no Colored girl has done. They fly.” Bessie became determined to prove them and society wrong by applying to multiple aviation schools in the U.S.

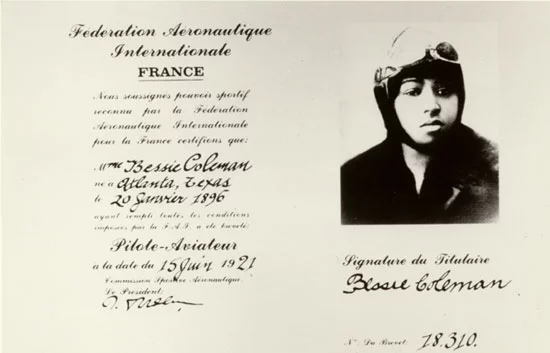

Bessie Coleman's aviation license. PF-(aircraft)/Alamy Stock Photo

BREAKING BARRIERS

Bessie was rejected from all of the U.S. aviation schools she applied to, simply because she was African American and a woman. She then sought advice from Robert Abbott, a wealthy friend and founder of the African American-run newspaper The Chicago Defender. Abbott suggested that Bessie study French and prepare to go to a French aviation school. When she arrived in Paris, the aviation school she was planning on attending was not accepting women due to the deaths of two female students. Instead, Bessie was accepted by Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. She had to walk nine miles to school everyday for 10 months, yet she persevered and finished the course. It was there, in 1921, that Bessie broke racial and gender barriers by becoming the first woman of African American or Native American descent to earn an international pilot’s license.

"Do you know you have never lived until you have flown?"

~ Bessie Coleman, Chicago Defender Interview, October 8, 1921

ADAPTING TO INEQUALITY

After receiving her license, Bessie traveled back to the U.S. with hopes of less discrimination and more opportunities for black aviationists—however, this was not the case. Bessie soon found that because she was African American and a woman, she could not become a commercial pilot in the U.S. While there were no laws prohibiting female pilots, many employers would immediately turn down a young African-American woman simply because of discrimination in society during that time. Her only job option in the aviation field was barnstorming (an older term for stunt flying). Bessie took this in stride, soon becoming an aviation daredevil with the nickname “Queen Bess."

Bessie Coleman, January 1923. Gale in Context: High School

¨Queen Bess¨ Bessie Coleman. SDASM Archives/Creative Commons

SOARING ABOVE SEGREGATION

As Bessie became more of a public figure, she developed her own set of requirements for her performances. She refused to perform at shows where African Americans were not allowed, and would only perform for crowds that were not segregated. Bessie was offered a movie role, where she would be acting as herself, but when she realized that she would be portraying African Americans in a negative way in the film she immediately refused.

Bessie spoke in schools and churches around the country, encouraging others to break through stereotypes and barriers. She inspired other African Americans to learn to fly and started raising money to open her own flight school for African-Americans. Sadly, she was unable to accomplish this goal. In 1926, Bessie fell 2,000 feet to her death in a tragic aviation accident.